Redirection of Root Cause Analysis old page

This page has been moved…https://medicaldeviceacademy.com/root-cause-analysis/

Redirection of Root Cause Analysis old page Read More »

The author describes four tools (Five Why Analysis, Is/Is Not Analysis, Fishbone Diagram, and Pareto Analysis) and how each one can help conduct effective root cause analysis.

Quality problems are like weeds. If you don’t pull them out by the root, they grow right back.

Most companies are doomed to repeat their mistakes because the root cause of their mistakes is not fixed. Why don’t companies fix their mistakes? Because the people responsible for the corrective actions (CAPA), were not adequately trained on root cause analysis. Adequate training on root cause analysis requires three things:

If your auditor identifies a nonconformity and you disagree with the finding, then you should not accept the finding and state your case. If an inspector rejects a part, and you believe the part is acceptable, then you should allow the part to be used “as is.” In both of these cases, however, you need to be very careful. Sometimes the problem is that “acceptable” is not as well-defined as we thought. I recommend pausing a moment and reflecting on what your auditors and inspectors are saying and doing. You may realize that you caused the problem.

Once you have accepted that there is a problem, you need to learn how to analyze the problem. There are five root cause analysis tools that I recommend:

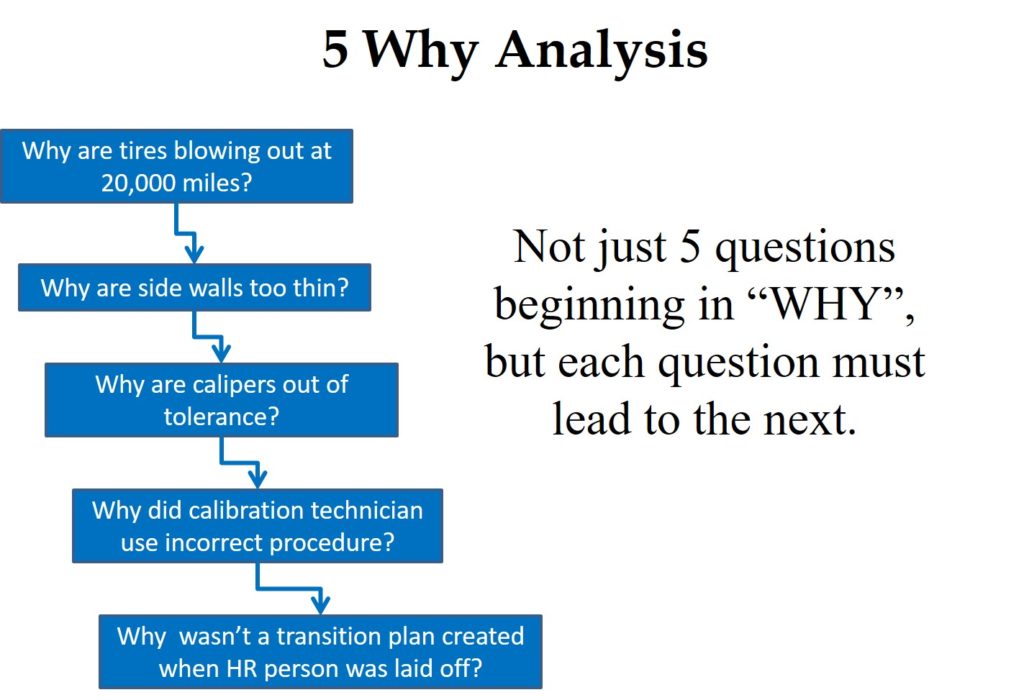

A “Five Why Analysis” is not just five questions that begin with the word “why.” Taiichi Ohno is credited with institutionalizing the “Five Why Analysis” at Toyota as a tool to drill down to the root cause of a problem by asking why five times. I have read about this, used this tool, and taught this concept to students, but I learned of a critical instruction that I was missing when I read Toyota Under Fire.

In that book, Jeff Liker makes the following statement, “Toyota Business Practices dictates using the ‘Five Whys’ to get to the root cause of a problem, not the ‘Five Whos’ to find a fire the guilty party.” At the end of the book, there are lessons learned from Toyota’s experience. Lesson 2 says, “There is no value to the Five Whys if you stop when you find a problem that is outside of your control.” If your company is going to use this tool, it is important that the responsible person is the one performing the five why analysis, and asks why they didn’t take into account forces that are out of their control.

The next tool was presented to me at an AAMI course that I attended on CAPA. One of the instructors was from Pathwise, and he explained the “Pathwise Process” to us for problem-solving. A few years later, I learned that this tool is called the “Is/Is Not Analysis.” This tool is intended to be used when you are having trouble identifying the source of a problem. This method involves asking where the problem is occurring as a potential clue to the reason for the problem. For example, if the problem only occurs on one machine, you can rule out a lot of possible factors and focus on the few that are machine-specific.

The reverse approach is also used to help identify the cause. You can ask where the problem is not occurring. This approach may also lead you to possible solutions to your problem. For example, if the problem never occurs on the first or second shift, you should focus on the processes and the people that work on the third shift to locate the cause. The “Is/Is Not Analysis” is seldom used alone, but it may be the first step toward locating the cause of a quality problem.

This name comes from the shape of the diagram. Other names for this diagram are the “Cause and Effect” or “Ishikawa” diagram. If a problem is occurring in low frequency and has always existed, this might not be your first tool. However, I typically start with this tool when I am doing an investigation of nonconforming product—especially when rejects suddenly appear.

If you are baffled about the cause of a problem, brainstorming the possible causes in a group sometimes works. However, I like to organize and categorize the ideas from a brainstorming session into the “6Ms” of the Fishbone Diagram.

The fourth root cause analysis tool is the Pareto Analysis named after Antoine Pareto. This tool is also a philosophy that was the subject of a book called The 80/20 Principle: The Secret to Achieving More with Less. The Pareto Analysis is used to organize a large number of nonconformities and prioritize the quality problems based upon the frequency of occurrence. The Pareto Chart presents each challenge in descending order from the highest rate to the lowest frequency. After you perform your Pareto Analysis, you should open a CAPA for the #1 problem, and then open a CAPA for the #2 problem. If you get to #3, consider yourself lucky to have the time and resources for it. We have an example of a Pareto Chart in our article on FDA 483 inspection observations from 2013.

If you are interested in learning more about root cause analysis and practicing these techniques, please register for the Medical Device Academy’s Risk-Based CAPA training.

Root cause analysis – Learn 4 tools Read More »

Do you have suggestions for future webinars? Visit our Suggestion Box.

Our latest YouTube short.

Below is a countdown clock for our next live-stream YouTube video and the schedule for the new live webinars we are hosting. Our next YouTube Live-streaming video will be on Friday @ 12:30 pm ET (August 2, 2024). The next live-streaming YouTube video will discuss “What’s the link between a DHF and a 510(k) in the context of design reviews?”

If you want to be notified of new webinars another way, including the paid webinars that we do not post on our YouTube channel, please subscribe to our email webinar notification list using the form below:

In addition to the webinars available for purchase on this page, you can also watch videos that we have posted on our YouTube channel. If you are a channel subscriber, you will receive automatic notifications of new YouTube postings on our channel by clicking on the notification bell. The time remaining until our YouTube live-streaming video is shown below, and please don’t forget to email Rob your questions at rob@13485cert.com.

The following is a list of quality and regulatory training webinars that are available for on-demand purchase from this website. If you subscribe to our email notification list using the form on the right, we will notify you by email of any new webinars when we add them to this page. You can also suggest new topics by submitting your idea to the Suggestion Box.

Free Webinars (Don’t forget to subscribe to our YouTube Channel)

Webinars and Live-Stream YouTube Videos Coming Soon Read More »

Your CAPA procedure is the most important SOP. It forces you to investigate quality problems and take actions to prevent nonconformity.

Procedures are often unclear because the author is more familiar with the process than the intended audience for the procedure. An author may abbreviate a step or skip it altogether. As an author, you should use an outline format and match your CAPA form exactly. There should be nothing extra in the procedure, and nothing left out. Medical Device Academy’s updated CAPA procedure is only six pages and the CAPA form is four pages.

The CAPA procedure webinar will be hosted on July 22, 2024 @ 10:30 a.m. ET. The webinar will be live, and you will receive login instructions if you purchased the CAPA procedure prior to the scheduled live webinar. The webinar will also be recorded. You will be able to download the webinar from our Dropbox folder and watch the webinar as many times as needed–including the training of future employees.

The following items are included with the purchase of the CAPA procedure:

This CAPA procedure includes a webinar, but the focus is on implementing the procedure and customizing it for your company. In contrast, the risk-based CAPA training webinar explains the details of performing a CAPA investigation, identifying the root cause, writing a corrective action plan, and performing effectiveness checks. The risk-based CAPA training is recommended for anyone without prior CAPA experience.

Procedures are often unclear because the author is an expert with more experience than the intended audience. An author may abbreviate a step or skip it altogether. As an author, you should use an outline format and match your CAPA form exactly. There should be nothing extra in the procedure, and nothing left out. Before writing your own CAPA procedure, consider following these 7 steps:

The specific order of steps is essential to creating a CAPA procedure—or any procedure. Writing a procedure that matches the form used with that procedure helps people understand the tasks within a process. Throughout the rest of this article, we describe each of the nine steps of Medical Device Academy’s CAPA procedure (SYS-024). The actual CAPA form (FRM-009) sold with SYS-024 is more complex than 9 steps, but a more complex form is needed to make sure every sub-task is documented in your CAPA records.

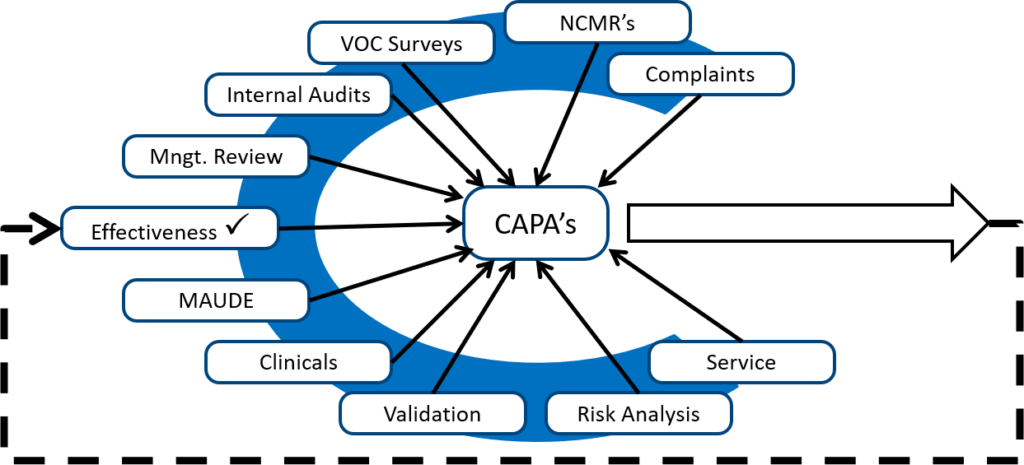

If I am auditing a CAPA process, and almost all the CAPAs are resulting from auditor findings, then I know the client is not adequately reviewing other sources of potential quality issues. When I took my first CAPA training course, the image below was drawn on a flip chart by Kim Trautman. I have used this image in all of my CAPA training for other people since. I think this provides a good visual representation of the most common sources of new CAPAs. Although the number of CAPAs from each source will never be equal, you should review all of these data sources for quality issues periodically.

The next step is to copy and paste your quality issue directly into the CAPA record and add a reference to the source. This step of the CAPA procedure is not a specific requirement of the ISO 13485 standard or the FDA regulations. However, describing and referencing quality issues in your CAPA record is a practical requirement. The person assigned to investigate the root cause of the quality issue needs to know what the source of the quality issue is, and when you are trying to close a complaint or audit report you will find it helpful to cross-reference the two records. For example, the CAPA might be related to the fifth nonconformity in your second internal audit report for 2022 (e.g. IA 220205).

Attribution: Icons were copied and pasted from Flaticon.com.

Why can’t we fix our mistakes the first time? We are doomed to repeat mistakes when we fail to identify the root cause or causes. The person you assign to investigate a quality issue must be trained to perform a thorough root cause analysis. Successful root cause analysis depends upon four things:

The common belief is that people fail to identify the root cause because they need root cause training (#2) or more practice (#3). However, most people fail because they stop sampling or testing too soon. I typically recommend that companies sample at least twice as many records as the suspected problem frequency. For example, if a complaint occurs 1% of the time, you should review 200 records before you can be sure you identified that root cause. If you are correct, you will only find the quality issue twice in the 200 records. However, a review of 200 records often reveals that the quality problem is more common than you originally estimated and there is more than one cause of device malfunction.

After you have successfully completed a root cause analysis, you now need to determine if a new CAPA is needed. If there is already a CAPA that is open for the same quality issue, you can use the existing CAPA as justification for not conducting corrective actions. In this case, you should include a cross-reference in the new CAPA record to the existing CAPA record. You should also document containment measures and corrections.

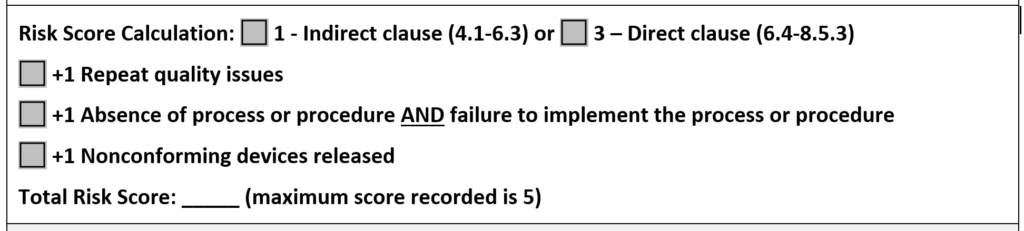

In both the existing CAPA record and your new CAPA record you should also be documenting your risk evaluation of your CAPA. In the latest update to our CAPA procedure, we changed the method of risk evaluation to match the MDSAP grading process for nonconformities. A copy of this section is provided in the image below.

In the CAPA procedure, we state that any risk score of 4 or 5 requires the implementation of a CAPA. If any of the escalation rules apply to the risk score, you should implement a CAPA regardless of the total risk score. This is our recommendation for a method of risk evaluation, but there is no standard telling you that you must do it this way. However, we believe this method of calculation is more likely to be consistent because it is based on the MDSAP grading guidelines.

If no escalation rules apply to your risk score, it may be possible to implement containment and corrections only. If your action plan includes only containment and corrections, we recommend that you monitor the quality issue as a process metric or quality objective to identify future occurrences. If you are evaluating a new CAPA that appears to have the same root cause as an existing CAPA, you may need to update the risk score of the existing CAPA to a higher number based on the escalation rules. Escalation may impact your corrective action plan, and it should certainly affect the prioritization of your existing CAPA.

The biggest mistake you can make in this stage of the CAPA process is to spend too much time planning your corrective actions. “Take action and document it” is the essence of this step in the CAPA procedure. If you spend all of your time planning, then you will never take action. The CAPA plan can and should be edited. Therefore, if you know a procedure needs revision, start revising the procedure immediately. You can always add more corrective actions to your corrective action plan after you write the procedure, but you need to start writing. The second biggest mistake you can make during this stage is failing to document the actions you take. If you don’t document your actions, it’s a rumor, not a record.

One of the required actions for a CAPA is to update your procedure(s) to reflect any process improvements to eliminate the root cause. When you update procedures, you need to make sure procedural changes do not create a regulatory compliance issue. We do this by inserting a cross-reference to each regulatory requirement in our procedures. The cross-reference is then color-coded and we add a symbol for people that are color blind. Symbols also facilitate electronic searches for regulatory requirements.

If corrective actions you implement involve design changes you will need to repeat design verification and design validation to make sure design changes do not impact safety and performance. If corrective actions change your manufacturing or service processes, you will need to repeat process validation to make sure that the process changes do not impact compliance with your design specifications. These recertification and revalidations steps are frequently forgotten, and they represent the biggest challenge for review and approval of design and process changes (described in the video below).

Most people verify CAPA effectiveness by verifying that all the actions planned were completed, but this is not a CAPA effectiveness check. An effectiveness check should use quantitative data from your investigation of the root cause as a benchmark. Then you should verify that the performance after corrective actions is implemented resulted in a decrease in the frequency of the quality problem, a decrease in the severity of the quality problem, or both. Ideally, a process re-validation was performed because validation protocols are required to include quantitative acceptance criteria for success.

You are required to record each step of your CAPA procedure in a CAPA record (FRM-009). Therefore, we created a form that is organized in the order of the CAPA process, and then we wrote the CAPA procedure to match the organization of the form. The biggest mistake we see is that the CAPA owner does not update the record to include all of the details until the CAPA plan is completely implemented. This is a mistake. You should be documenting actions when they are taken. When you gather new information, and you need to update your root cause investigation or your corrective action plan, you are allowed to modify the record. You just need to have a system that allows you to keep track of revisions. This is often referred to as an “audit trail.” If you have a paper-based system, you will need to sign and date the document each time you make an addition. If you revise previous entries, you will need to revise and reprint the CAPA record, and then you will need to sign and date the revised and reprinted CAPA record. Ideally, you will have an electronic system with an audit trail, but software budgets are not infinite.

The last step in the CAPA procedure is to close your CAPA record. As with most quality system records, the person responsible for the process should review and approve each record for closure with a signature and date. If the person assigned to the CAPA left sections incomplete or made mistakes in completing the CAPA form, the person that made the mistake should be instructed to correct the mistake, identify that they made a correction, and identify the date of the correction. If a CAPA is not effective, then a cross-reference to the new CAPA that is opened should be documented in the older CAPA record.

If you are interested in more training on CAPA, you might be interested in purchasing Medical Device Academy’s Risk-Based CAPA webinar. 99% of companies hold off on their training until a procedure is officially released as a controlled document. In my experience, however, these procedures seem to have a lot of revisions made immediately after the initial release. New users ask simple questions that identify sections of procedures that are unclear or were written out of sequence. Therefore, you should always conduct at least one training session with users prior to the final review and approval of a procedure. This will ensure that the final procedure is right the first time, and it will give those users some ownership of the new procedure.

After you train your initial group, and after you make the edits they recommended, ask those trainees to review and edit your changes to the procedure. Sometimes we don’t completely understand what someone is describing, and sometimes maybe only half-listening. Going back to those people to verify that you accurately interpreted their feedback is the most important step for ensuring that users accept your new procedure.

After you approve your new CAPA procedure, make sure everyone in your company is trained on the final version of the procedure. CAPA is a critical process (i.e., “the heart”) in your quality system. Everyone should understand it. You should also provide extra CAPA training for department managers, such as root cause analysis training because they will be responsible for implementing CAPAs assigned to their department. You can use this 7-step process for any procedure, but ensure you use it for the most important process of all—your corrective and preventive action process.

Thank you for reading to the end of this article. Spaz and I thank you for your support.

CAPA Procedure (SYS-024) and Webinar Read More »

This is part one of a case study on how to perform a packaging complaint investigation when packaging is found open by a customer.

This case study example involves a flexible, peelable pouch made of Tyvek and a clear plastic film. This is one of the most common types of packaging used for sterile medical devices. In parallel with the complaint investigation, containment measures and corrections are implemented immediately to prevent the complaint from becoming a more widespread problem. The investigation process utilizes a “Fishbone Diagram” to identify the root cause of the packaging malfunction. This is just one of several root cause analysis tools that you can use for complaint investigations, but it works particularly well for examples where something has gone wrong in production process controls, but we are not sure which process control has failed.

The first step of the complaint handling process (see SYS-018, Customer Feedback and Complaint Handling) is to record a description of the alleged quality issue. A distributor reported the incident that was reported. The distributor told customer service that two pouches in a box containing 24 sterile devices were found to have a seal that appeared to be delaminating. Unfortunately, the distributor was unable to provide a sample of the delaminated pouches or the lot number of the units. Packaging issues and labeling issues are typically two of the most common complaint categories for medical devices. Often the labeling issues are operator errors or a result of labeling mixups, while the packaging errors may be due to customers who accidentally ordered or opened the wrong size of the product. Therefore they may complain about packaging when there is nothing wrong. It is essential to be diligent in the investigation of each packaging complaint because if there is a legitimate packaging quality issue, then there may be a need for a product recall as part of your corrective action plan.

In your complaint record, you need to assign a person to investigate the complaint. The only acceptable reason for not initiating an investigation is when a similar incident was already investigated for another device in the same lot or a related lot (i.e., packaging raw material lot is the same and the problem is related to the material). If the complaint was already investigated, then the complaint record should cross-reference the previous complaint record.

The person assigned to investigate the complaint must be trained in complaint investigations and should be technically qualified to investigate the processes related to the complaint (e.g., packaging process validation). The investigator must record which records were reviewed as part of the investigation, and the investigation should be completed promptly in case regulatory reporting is required or remedial actions are needed. It is also necessary to demonstrate that complaints are processed in a consistent and timely manner (e.g., average days to complaint closure may be a quality objective).

We know everyone wants to avoid regulatory reporting because we are afraid that other customers will lose confidence in our product and bad publicity may impact sales. However, the consequences of failing to file medical device reports with the FDA are much worse. Even if an injury or death did not occur with a sterile medical device, the quality issue should still be reported as an MDR under 21 CFR 803 (see SYS-029, Medical Device Reporting) because a repeat incident could cause an infection that could result in sepsis and death. If you think that this is an extremely conservative approach, you might be surprised to learn that 251 MDRs were reported to the FDA in Q4 of 2023 for packaging issues. Of these reports, only one involved an actual injury, and the other 250 involved a device malfunction but no death or injury. The following event description and manufacturer’s narrative is an example:

“It was reported by the sales rep in japan that during an unspecified surgical procedure on (b)(6) 2023 the rgdloop adjustable stnd device sterile package was not sealed and was unclean.Another like device was used to complete the procedure.There was an unknown delay in the procedure reported.There were no adverse patient consequences reported.No additional information was provided.”

“This report is being submitted in pursuant to the provisions of 21 cfr, part 803.This report may be based on information which has not been able to investigate or verify prior to the required reporting date.This report does not reflect a conclusion by mitek or its employees that the report constitutes an admission that the device, mitek, or its employees caused or contributed to the potential event described in this report.If information is obtained that was not available for the initial medwatch, a follow-up medwatch will be filed as appropriate.Device was used for treatment, not diagnosis.If information is obtained that was not available for the initial medwatch, a follow-up medwatch will be filed as appropriate.H10 additional narrative: e3: reporter is a j&j sales representative.H4: the device manufacture date is unknown.Udi: (b)(4).”

What the narrative above does not elaborate on is what was the specific investigation details for “lot history reviewed.” One of the most useful tools for performing a packaging complaint investigation is the “Fishbone Diagram.” Other names include, “Ishikawa Diagram” and “Cause and Effect Diagram.” There are six parts (i.e., “6Ms”) to the diagram:

The following records could be reviewed and evaluated for potential root causes even if the customer does not return the packaging with the alleged malfunction:

If all of the above fail to identify a potential cause for a packaging failure, then you might have a problem related to people or the environment. People include the people sealing the product package and the users. The environment consists of the temperature and humidity for storage of packaging raw materials, packaged products, sterilization conditions, storage conditions after sterilization, and shipping conditions–including any temporary extremes that might occur during transit.

In our case study, the product was not returned, and we did not have the lot numbers. Therefore, we may need to review distribution records to that distributor and/or the customer to narrow down the possible lots to one or more lots. Then we would need to perform the same type of review of lot history records for each potential lot. The best approach is to request a photo of the package labeling, including the UDI bar code, because that information will facilitate lot identification. Even if the product was discarded, often the UDI will be scanned into the patient’s electronic medical record (EMR) during surgery.

Sometimes you are fortunate enough to receive returned products. The product should be immediately segregated from your other products to prevent mixups and/or contamination. Normally the returned products are identified as non-conforming products and quarantined. After the quarantined product is evaluated for safety, the assigned investigator may inspect the packaging in a segregated area. Packaging investigations begin with visual inspection following ASTM F1886. If multiple packaging samples are available, or the packaging is large enough, the investigator may destructively test (i.e., ASTM F88) a 1” strip cut from the packaging seal to verify that the returned packaging meets the original specifications. If you kept retains of packaging with the same lot of flexible packaging, you may visually inspect and destructively test retains as well.

Once the root cause is identified for a packaging complaint, then you need to implement corrective actions to prevent a recurrence. Also, FDA Clause 21 CFR 820.100 and ISO 13485, Clause 8.5.3, require that you implement preventive actions to detect situations that might result in a potential packaging failure in the future and implement preventive measures so that similar packaging failures are not able to occur. If you are interested in learning more about conducting a root cause analysis, please read our blog on this topic: Effective Root Cause Analysis – Learn 4 Tools.

This article is the first half of the packaging complaint investigation case study. The second half of the two-part case study explains the necessary containment measures, corrections, corrective actions, and preventive actions to address the root cause of the packaging failure.

There are many articles on the topic of package testing and package design for sterile medical devices. If you want to learn more, please register for our free webinar on packaging validation by Jan Gates.

Packaging Complaint Investigation – Case Study Read More »

90% of usability testing submitted to the FDA is unacceptable and the root cause is simply a failure to understand the human factors process.

If you submitted no usability testing to the FDA in your 510(k) submission, it would be obvious why the FDA reviewer identified usability as a major deficiency. However, you spent tens of thousands of dollars on usability testing that delayed the 510(k) submission by six months. Despite all of the time and money your company invested in the human factors process, it appears that you need to start over and repeat the entire process again. The CEO is furious, and he wants you to show him where in the 49-page FDA guidance it says that you have to do things differently.

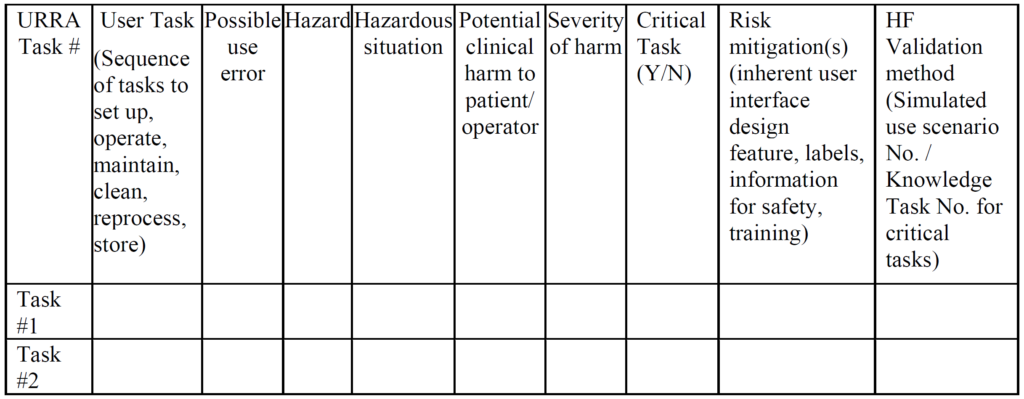

Unlike CE Marking technical files, the FDA does not require a usability engineering file for all products. Instead, the FDA determines if usability testing is required based on a comparison of your device’s user interface and a competitor’s user interface (i.e. predicate device user interface). If the user interface is identical, then usability testing may not be required. Instead, your company should be able to write a rationale for not doing usability testing based on equivalence with the predicate device. If there are differences in your user interface, you will need to provide use-related risk analysis (URRA), identify critical tasks, implement risk controls, and provide verification testing to demonstrate the effectiveness of the risk controls. Even if your device is “easier to use” or “simpler”, you still need to provide the documentation to support this claim in your submission. The FDA also does not allow comparative claims in your marketing for 510(k) cleared devices. Comparative claims require the support of clinical data.

There is a YouTube video describing these 10 steps at the bottom of this blog posting.

The primary problem with using an FMEA or Fault-Tree risk analysis tool is that these tools involve the estimation of the severity of harm and the probability of occurrence of harm, while the FDA does not feel it is appropriate to estimate the probability of occurrence of harm. Instead, the FDA instructs companies to assume that use errors will occur and to implement risk controls to mitigate those risks (see URRA example above). Although “mitigation” is unlikely, and use risks will only be reduced, this is the approach the FDA wants companies to use. In addition, the FDA expects your company to provide traceability of risk control implementation to each use-related risk you identified and the FDA expects documentation of verification testing (i.e. usability testing) that shows your risk controls are effective. Finally, the FDA (and ISO 14971, Clause 10) expects you to collect and perform a trend analysis of use errors. Any use errors that are reported should be evaluated for the need to implement additional corrective actions to prevent future use errors. Blaming “user error” is not an acceptable approach.

Therefore, if you are developing imaging software, you need to make sure your user group includes radiologists that cover the entire range of competencies. In addition, most radiology images are taken by radiology technicians and then reviewed by the radiologist. Therefore, radiology technicians should be considered a completely different user group due to the differences in experience, training, and competency when compared to a radiologist. This simple example doubles the number of users needed because you have two user groups instead of one.

Human factors process, can we make this easy? Read More »

Learn how to become ISO 13485 certified while avoiding the stress that tortures other quality system managers.

ISO 13485 is an international standard for quality management systems that is specific to the medical device industry. ISO 13485:2016 is the most recent version of the standard, and it has become the blueprint for medical device company quality systems globally. If your company wants to design, manufacture, or distribute medical devices you should consider becoming ISO 13485 certified.

Yes, you need to maintain a copy of the ISO 13485 standard as a “document of external origin.” This is needed for reference when you are making updates to procedures in your quality system. If you are looking for the best place to purchase a copy of the ISO 13485:2016 standard, we recommend the Estonian Centre for Standardisation and Accreditation. If you purchase a copy, we recommend selecting the option for a multi-user license so the standard can be used by more than one person in your company and printed. The only difference between the EN ISO version and the International ISO version is that the EN ISO version includes harmonization Annex ZA for compliance with the EU MDR and Annex ZB for compliance with the EU IVDR. This version is also referred to as A11:2021. Here’s a copy of the text from the beginning of the Standard:

“This Estonian standard EVS-EN ISO 13485:2016/A11:2021 consists of the English text of the European standard EN ISO 13485:2016/A11:2021. This standard has been endorsed with a notification published in the official bulletin of the Estonian Centre for Standardisation and Accreditation. Date of Availability of the European standard is 08.09.2021. The standard is available from the Estonian Centre for Standardisation and Accreditation.”

Rob Packard created his first quality system in the Spring of 2004. In October 2009, after successfully managing quality systems for three different medical device manufacturers, Rob joined BSI as a Lead Auditor and instructor. In April 2010, he purchased the 13485cert.com URL and he began to help companies implement quality systems as a consultant (while continuing to audit and train 140 days per year for BSI). In 2011 his medical device blog postings began as a way to help medical device companies. In 2012, Rob began building a library of quality system procedures for a turn-key quality system and selling the procedures from the Medical Device Academy website. Dozens and dozens of consulting clients have successfully achieved ISO 13485 certification with Medical Device Academy’s turnkey quality system procedures, and hundreds of quality systems were audited and/or improved. This ISO 13485 training webinar is also included as part of our turnkey quality system.

On February 23, 2022, the FDA published a proposed rule for medical device quality system regulation amendments. The FDA planned to implement amended regulations within 12 months, but the consensus of the device industry is that a transition of several years would be necessary. In the proposed rule, the FDA justifies the need for amended regulations based on the “redundancy of effort to comply with two substantially similar requirements,” creating inefficiencies. The FDA also provided estimates of projected cost savings resulting from the proposed rule. What is completely absent from the proposed rule is any mention of the need for modernization of device regulations.

The QSR is 26 years old, and the regulation does not mention cybersecurity, human factors, or post-market surveillance. Risk is only mentioned once by the regulation, and software is only mentioned seven times. The FDA has “patched” the regulations with guidance documents, but there is a desperate need for new regulations that include critical elements. The FDA has “patched” the regulations through guidance documents, but there is a desperate need for new regulations that include critical elements. The transition of quality system requirements for the USA from 21 CFR 820 to ISO 13485:2016 will force regulators to establish policies for compliance with each of these quality system elements. Companies that do not already have ISO 13485 certification should be proactive by 1) updating their quality system to comply with the standard and 2) adopting the best practices outlined in the following related standards:

This 2-part webinar has been previously recorded three different times. Our previous webinar on the 2003 version of ISO 13485 was split into two parts: Stage 1 and Stage 2. That first webinar was recorded in 2015. The webinars were updated in 2016 and again in 2018. We followed the same format, 2-part Stage 1 and Stage 2, for all of the subsequent ISO 13485 training webinars. The Stage 1 webinar focuses on the following processes:

The Stage 2 webinar on the rest of the standard, including but not limited to:

The webinars explaining the requirements for ISO 13485 were last updated in 2020. Anyone who purchases these webinars will receive free access to updated versions of the ISO 13485 training webinars. If you are making a new purchase of these two training webinars, the webinars are only being sold as a bundle for $258. You get:

This pair of ISO 13485 training webinars explain precisely what you need to do to implement a quality system compliant with ISO 13485. After you create your own plan (a free template is provided with a subscription), you can show the recording of these two webinars to your management team so they can implement your plan in the next several months. All deliveries of content will be sent via Aweber emails to confirmed subscribers.

Webinars were hosted live via Zoom in 2020. The Stage 1 webinar was 64 minutes, and the duration of the Stage 2 webinar was 82 minutes. When you purchase this webinar bundle, you will receive a link to download both recorded webinars from our Dropbox folder. In addition, you will receive links to download the native slide deck for each webinar from Dropbox.

There is a big difference between being ISO 13485 certified and being compliant with ISO 13485:2016, the medical devices quality management systems standard. Anyone can claim compliance with the standard. Certification, however, requires that an accredited certification body has followed the requirements of ISO 17021:2015, and they have verified that your quality system is compliant with the standard. To maintain that certification, you must maintain your quality system’s effectiveness and endure both annual surveillance audits and a re-certification audit once every three years.

Step 1 – Planning for ISO 13485 certification

There are six steps in the ISO 13485 certification process, but that does not mean there are only six tasks. The first step in every quality system is planning. Most people refer to the Deming Cycle or Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) Cycle when they describe how to implement a quality system. However, when you are implementing a full quality system, you need to break the “doing” part of the PDCA cycle into many small tasks rather than one big task. You also can’t implement a quality system alone. Quality systems are not the responsibility of the quality manager alone. Implementing a quality system is the responsibility of everyone in top management.

Below you will find seven tasks listed. I did NOT identify these nine tasks as “Steps” in the ISO 13485 certification process, because these tasks are typically repeated for each process in your quality system. Most quality systems are implemented over time, and the scope of the quality system usually grows. Therefore, you are almost certain to have to perform all of the following nine tasks multiple times–even after you receive the initial ISO 13485 certification. As the saying goes, “How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.” Therefore, avoid the inevitable heartburn caused by trying to do too much at one time. Implement your quality system one “bite” at a time.

The first task in implementing an ISO 13485 quality system is to purchase a copy of the ISO 13485:2016 standard, such as the MDSAP Companion Document. You will also need other applicable medical device standards. Some of these standards are general standards that apply to most, if not all, medical devices, such as ISO 14971:2019 for risk management. There are also guidance documents that explain how to use these general standards, such as ISO/TR 24971:2020, and guidance on how to apply ISO 14971:2019. Finally, there are testing standards that identify testing methods and acceptance criteria for things such as biocompatibility and electrical safety. You will need to monitor these standards for new and revised versions. When these standards are updated, you will need to identify the revised standard and develop a plan for addressing the changes.

When you purchase a standard, be sure to buy an electronic version of the standard so you can search the standard for keywords efficiently. You should also consider purchasing a multi-user license for the standard because every manager in your company will need to look up information in the standard. Alternatively, you could buy a paper copy of the standard and locate the standard where everyone in your company can access it. Often I am asked what the difference is between the EN version of the standard and the ISO version of the standard. “EN” is an abbreviation meaning European Standards or “European Norms,” which is based upon the literal translation from the French (i.e., “normes”) and German (i.e. “norm”) languages. “ISO” versions are international standards. In general, the body of the standard is typically identical but harmonized EN standards for medical devices include annexes ZA, ZB, and ZC that identify any deviations from the requirements in three medical device directives (i.e., MDD, AIMD, and IVDD).

Clause 1 of ISO 13485 is specific to the scope of a quality system. ISO 9001, the general quality system standard, allows you to “exclude” any clause from your quality system certification. However, ISO 13485 will only allow you to exclude design controls (i.e., clause 7.3). Other clauses within ISO 13485 may be identified as “non-applicable” based on the nature of your medical device or service. You must also document the reason for non-applicability in your quality manual. Typically, the following clauses are common clauses identified for non-applicability:

The third task is to assign a process owner to each of the processes in your quality system. Typically, you create a master list of each of the required processes. Usually, the assignments are made to managers in the company who may delegate some or all of a specific process. You should expect most managers to be responsible for more than one process because there are 28 required procedures in ISO 13485:2016, but most companies have fewer than ten people when they first implement a quality system.

The fourth task is to identify which processes need to be created first and to schedule the implementation of procedures from first to last. You can and should build flexibility into the schedule, but some procedures are needed at the beginning. For example, you need document control, record control, and training processes to manage all of your other procedures. You also need to implement the following processes to document your Design History File (DHF): 1) design controls, 2) risk management, 3) software development (if applicable), and 4) usability. Therefore, these represent the seven procedures that most companies will implement as early as possible. Procedures such as complaint handling, medical device reporting, and advisory notice procedures are usually reserved for last. These procedures are last because they are not needed until you have a medical device in use.

Forms create the structure for records in your quality system, and a well-designed form can reduce the need for lengthy explanations in a procedure or work instruction. Therefore, you should consider developing forms first. The form should include all required information that is specified in the applicable standard or regulations, and the cells for that information should be presented in the order that the requirements are listed in the standard. You might even consider numbering the cells of the form to provide an easy cross-reference to the corresponding section of the procedure. Once you create a form, you might consider creating a flowchart next. Flowcharts provide a visual representation of the process. You might consider including numbers in the flow chart that cross-reference to the form as well.

Once you have created a form and a flowchart, you are now ready to write your quality system procedure. Many sections are typically included in a procedure template. It is recommended that you use a template to ensure that none of the basic elements of a procedure are omitted. You might also consider adding two sections that are uncommon to a procedure: 1) a risk analysis of the procedure with the identification of risk controls to prevent risks associated with the procedure, and 2) a section for monitoring and measurement of the process to objectively measure the effectiveness of the process. These metrics are the best sources of preventive actions, and some of the metrics might be potential quality objectives to be identified by top management.

Most companies rely upon internal audits to catch missing elements in their procedures. However, audits are intended to be a sampling rather than a 100% comprehensive assessment. Therefore, when a draft procedure is being reviewed and approved for the first time, or a major rewrite of a procedure is conducted, a thorough gap analysis should be done before the approval of the draft procedure. Matthew Walker created an article explaining how to conduct a gap analysis of procedures. In addition, Matthew has been gradually adding cross-references to ISO 13485:2016 requirements in each procedure. He is color-coding the cross-referenced clauses in blue font as well. This makes it much easier for auditors to verify that a procedure is compliant with the regulations with minimal effort. The success of these two methods has taught us the importance of conducting a gap analysis of all new procedures.

You are required to document the training requirements for each person or each job in your company. Documentation of training requirements may be in a job description or within a procedure. In addition to defining who should be trained, you also need to identify what type of training should be provided. We recommend recording your training to ensure that new future employees receive the same training to ensure consistency. Design controls training should be the first priority. You are also required to maintain records of the training. You must verify that the training was effective, and you need to check whether the person is competent in performing the tasks. This training may require days or weeks to complete. Therefore, you may want to start training people several weeks before your procedure is approved. Alternatively, you can swap the order of tasks and conduct training after the procedure approval. If that approach is taken, then the procedure should indicate the date the procedure becomes effective–typically 30 days after approval to allow time for training.

Approval of a procedure may be accomplished by signing and dating the procedure itself, while another approach is to create a document that lists all the procedures and forms being approved at one time. The second method is the method we use in our turnkey quality system. Companies can review and approve as many procedures at one time as they wish. Since this process needs to be defined to ensure that all of the procedures you implement are approved, the document control process is typically the first procedure that companies will approve in a new quality system. The second procedure generally is for the control of records. Then the next procedures implemented will typically be focused on the documentation of design controls, risk management, usability testing, and software development. The last procedures to be approved are typically complaint handling, medical device reporting, and recalls. These procedures are left for last because you don’t need them until you are selling your medical device.

The last task required for the implementation of a new quality system is to start using the procedures to generate records. All of the procedures will need records before the process can be verified to be effective. Records can be paper-based, or the records can be electronic. Whichever format you use for the record retention needs to be communicated to everyone in the company through your Control of Records procedure and/or within each procedure. If you include the information in each procedure, the records of each procedure should be listed in the procedure, and the location where those records are stored should be identified. Generally, there is no specific minimum number of records to have for a certification audit, but you should have at least a few records for each process that you implement.

Step 2 – Conducting your first internal audit

The purpose of the internal audit is to verify the effectiveness of the quality system and to identify nonconformities before the certification body auditor finds them. To successfully achieve this secondary objective, it is essential to have a more rigorous internal audit than you expect for the certification audit. Therefore, the internal audit should be of equal duration or longer in duration than the certification audit. The internal audit should not consist of a desktop review of procedures. Reviewing procedures should be part of gap analysis (i.e., task 6 above) that is conducted on draft procedures before they are approved. Internal audits should utilize the process approach to auditing, and the auditor should apply a risk-based approach (i.e., focus on those processes that are most likely to contribute to the nonconforming products, result in a complaint, or cause severe injuries and death).

After your internal audit, you will receive an internal audit report from the auditor. You should also expect findings from the internal auditor, and you should expect opportunities for improvement (OFI) to be identified. Experienced auditors can typically identify the root cause of a nonconformity more quickly than most process owners. Therefore, it is recommended for each process owner and subject matter expert to review nonconformities with the auditor and discuss how the nonconformity should be investigated. The root cause must be correctly identified during the CAPA process, and the effectiveness check must be objective to ensure that problems do not recur.

Corrective actions should be initiated for each internal audit finding immediately, to make sure the findings are corrected and prevented from repeat occurrence before the Stage 1 audit. It will take a minimum of 30 days to implement the most corrective actions. Depending upon the scheduling of the internal audit, there may not be sufficient time to complete the corrective actions. However, you should at least initiate a CAPA for each finding, perform an investigation of the root cause, and begin to implement corrective actions.

Also, to take corrective actions related to internal audit findings, you should look for internal audits from other sources. The diagram below shows several different sources of potential corrective and preventive actions.

Monitoring and measuring each process is the best source of preventive actions, while internal audits are typically the best source of corrective actions. Any quality problems identified during validation are also excellent sources of corrective actions because the validation can be repeated as a method of demonstrating that the corrective actions are effective. However, your ISO 13485 certification auditor will focus on non-conforming products, complaints, and services as the most critical sources of corrective actions. These three sources are prioritized because these three sources have the greatest potential for resulting in serious injury, death, or recall if corrective actions are not implemented to prevent problems from recurring.

In addition to completing a full quality system audit before your stage 1 audit, you are also expected to complete at least one management review. To make sure that you have inputs for each of the 12 requirements in the ISO 13485:2016 standard, it is recommended to conduct your management review only after you have completed your full quality system audit and initiated some corrective actions. If possible, you should also conduct supplier audits for any contract manufacturers or contract sterilizers. It is recommended to use a template for that management review that is organized in the order of the required inputs to ensure that none of the necessary inputs are skipped. Quality objectives will need to be established long before the management review so that the top management team has sufficient time to gather data regarding each of the quality objectives. Also, you should consider delegating the responsibility for creating the various slides for each input to different members of top management. This will ensure that everyone invited to the meeting is engaged in the process, and it will spread the workload for meeting preparation across multiple people.

At the end of the meeting, top management will need to create a list of action items to be completed before the next management review meeting. Meeting minutes will need to be documented for the meeting, including the list of action items and each of the four required outputs of the management review process. We recommend using the notes section of a presentation slide deck to document the meeting minutes related to each slide. Then the slide deck can be converted into notes pages and saved as a PDF. The PDF notes pages will be your final meeting minutes for the management review. An example of one of these note pages is provided in the figure below.

One of the more common non-value-added findings by auditors is when an auditor issues a nonconformity because you do not have your next internal audit and your next management review scheduled–even though each may have occurred only a month prior to the Stage 1 audit. Therefore, we recommend that you document your next 12-month cycle for internal audits and schedule your next management review as action items in every management review meeting. The schedule can be adjusted if needed, but this allows top management to emphasize various areas in internal audits that may need improvement. You might even set a quality objective to conduct a minimum of three management reviews per year at the end of your first management review.

In 2006, the ISO 17021 Standard was introduced for assessing certification bodies. This is the standard that defines how certification bodies shall go about conducting your initial certification audit, annual surveillance of your quality system, and the re-certification of your quality system. In the past, certification bodies would typically conduct a “desktop” audit of your company before the on-site visit to make sure that you have all the required procedures. However, ISO 17021 requires that certification bodies conduct a Stage 1 audit that assesses the readiness of your company before conducting a Stage 2 audit. Therefore, even if the Stage 1 audit is conducted remotely, the certification body is expected to interview process owners and sample records to verify that the quality system has been implemented. Certification body auditors will also typically verify that your company has conducted a full quality system audit and at least one management review. Finally, the auditor will usually select a process such as corrective action and preventive action (CAPA) to make sure that you are identifying problems with the quality system and taking appropriate measures to address those problems.

Your goal for the Stage 1 audit should not be perfection. Instead, your focus is to make sure that there are no “major” non-conformities. The term “major” used to have a specific definition:

Under the MDSAP, the grading system for nonconformities now uses a numbering system for grading nonconformities: “Nonconformity Grading System for Regulatory Purposes and Information Exchange Study Group 3 Final Document GHTF/SG3/N19:2012.” Any nonconformity is graded on a scale of one to four, and then two potential escalation rules are applied. If any nonconformities are graded as a four or a 5, then the auditor must assess whether a five-day notice to Regulatory Authorities is required. A five-day notice is required in either of the following situations: 1) one or more findings grading of “5”; or 2) three or more findings graded as “4.” If your Stage 1 audit results in a five-day notice, then you are not ready for your Stage 2 audit. For example, a complete absence of two required procedures in clauses 6.4 through 8.5 of ISO 13485:2016 would result in two findings with a grading of “4.” This would not result in a five-day notice, but the absence of a third required procedure would result in a five-day notice.

The duration of your Stage 1 audit will be one or two days, but a 1.5-day audit is quite common for MDSAP Stage 1 audits. The reason for the 1.5-day Stage 1 audit is that it is challenging to assess readiness for Stage 2 in one day, and if the total duration of Stage 1 and Stage 2 is 5.5 days, then the Stage 2 audit could be completed in four days. The four-day audit is more convenient than a three-day audit for a two-person audit team.

After your Stage 1 audit, you will receive an audit report, and you should expect findings. You should initiate corrective actions for each finding immediately, to make sure the findings are corrected and prevented from repeat occurrence before the Stage 2 audit. The duration between the audits is typically about 4-6 weeks. That does not leave much time for you to initiate a CAPA, perform an investigation of the root cause, and implement corrective action. At a minimum, you must submit a corrective action plan for each finding to your MDSAP auditing organization (AO) within 15 calendar days of receiving the finding. For any findings graded as a “4” or higher, you will need to provide evidence of implementing the corrective action plan to the AO within 30 calendar days of receiving the finding. You are also unlikely to have enough time to conduct an effectiveness check prior to the Stage 2 audit.

The Stage 2 initial ISO 13485 certification audit will verify that all regulatory requirements have been met for any market you plan to distribute in. The auditor will complete an MDSAP checklist that includes all of the regulatory requirements for each of the countries that recognize MDSAP: 1) the USA, 2) Canada, 3) Brazil, 4) Austria, and 5) Japan. The auditor will also sample records from every process in your quality system to verify that the procedures and processes are fully implemented. This audit will typically be at least four days in duration unless multiple auditors are working in an audit team.

The audit objectives for the Stage 2 ISO 13485 certification audit specifically include evaluating the effectiveness of your quality system in the following areas:

All procedures will be reviewed for compliance with ISO 13485:2016 and the applicable regulations. The auditor will also sample records from each process. If the auditor identifies any nonconformities during the audit, it is important to record the findings and begin planning corrective actions immediately. If you have any questions regarding the expectations for the investigation of the root cause, corrections, corrective actions, and effectiveness checks, you should ask the auditor during the audit or the closing meeting. At a minimum, you must submit a corrective action plan for each finding to your MDSAP auditing organization (AO) within 15 calendar days of receiving the finding. For any findings graded as a “4” or higher, you will need to provide evidence of implementing the corrective action plan to the AO within 30 calendar days of receiving the finding. The auditor will not be able to recommend you for ISO 13485 certification until your corrective action plans are accepted.

If you receive a finding with a grading of “5,” or three or more findings graded as “4,” then the MDSAP auditor is required to issue a five-day notification to the regulators. The auditor will also need to return to your facility for a follow-up audit to close as many findings as they can. It is not necessary to eliminate all of the findings in order to be recommended for ISO 13485 certification, but the grading of the findings must be reduced to at least a “3” before recommending the company for certification. The number of findings also determines whether the auditor recommends your company for certification.

In addition to reviewing the findings and conclusions of the audit during the closing meeting, the auditor will also review the plan for the annual surveillance and re-certification with you. Each certification cycle is three years in duration. There will be two surveillance audits of approximately one-third of the duration of the combined duration of stage 1 and stage 2 initial certification audits, and the first surveillance audit must be completed within 12 months of the initial certification audit. In the third year, there will be a re-certification audit for two-thirds of the duration of the combined duration of stage 1 and stage 2 initial certification audits. The initial ISO 13485 certificate will be issued with a three-year expiration, and the certificate is typically received about one month after the acceptance of your corrective action plan.

There are no stupid questions, and we can save you weeks of wasted time if you just ask for help. We are always looking for new ideas for blogs, webinars, and videos on our YouTube channel. If you have any general questions about obtaining ISO 13485:2016 certification, please email Rob Packard at rob@13485cert.com. If you have a suggestion for new ISO 13485 training materials, you can also use our “Suggestion Box.” You can also schedule an initial free consultation with Rob using his calendly link.

About Your Instructor

Rob Packard is a regulatory consultant with ~25 years of experience in the medical device, pharmaceutical, and biotechnology industries. He is a graduate of UConn in Chemical Engineering. Rob was a senior manager at several medical device companies—including the President/CEO of a laparoscopic imaging company. His Quality Management System expertise covers all aspects of developing, training, implementing, and maintaining ISO 13485 and ISO 14971 certifications. From 2009 to 2012, he was a lead auditor and instructor for one of the largest Notified Bodies. Rob’s specialty is regulatory submissions for high-risk medical devices, such as implants and drug/device combination products for CE marking applications, Canadian medical device applications, and 510(k) submissions. The most favorite part of his job is training others. He can be reached via phone at 802.281.4381 or by email. You can also follow him on YouTube, LinkedIn, or Twitter.

ISO 13485 – Need training? Read More »

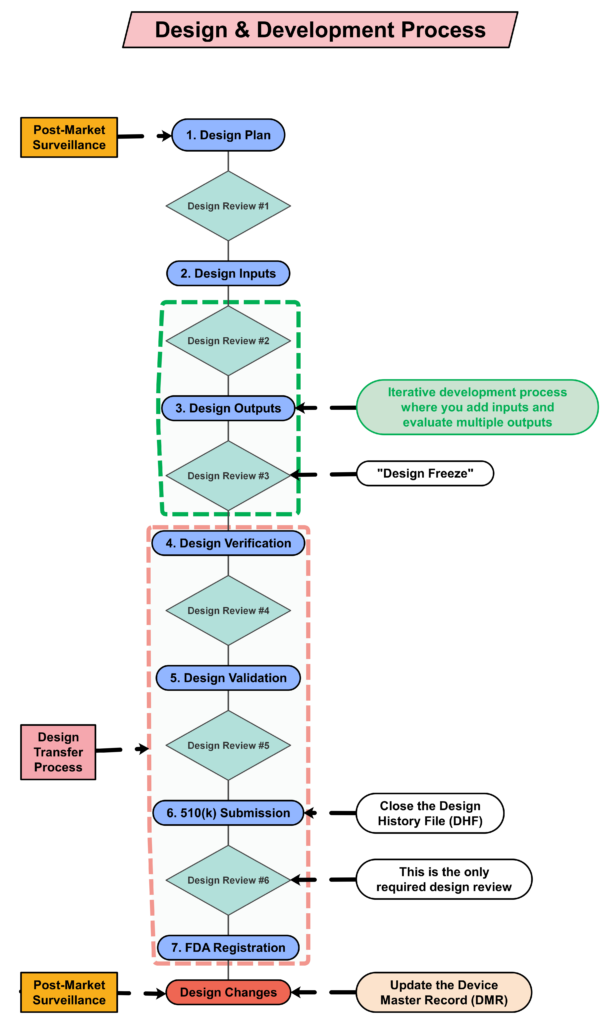

Design controls can be overwhelming, but you can learn the process using this step-by-step guide to implementing design controls.

Design Controls Implementation

Design Controls Implementation

You can implement design controls at any point during the development process, but the earlier you implement your design process the more useful design controls will be. The first step of implementing design controls is to create and design controls procedure. You will also need at least two of the following additional quality system procedures:

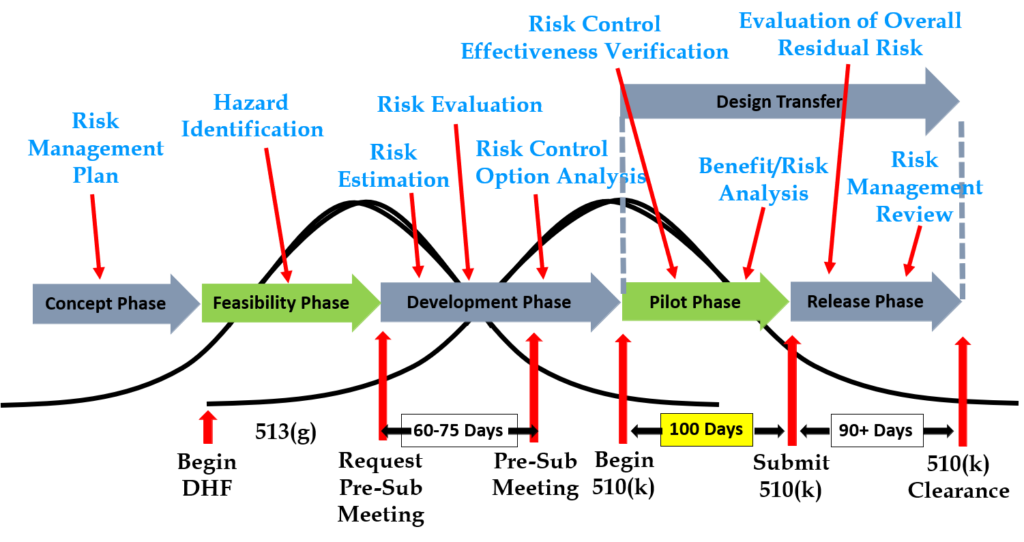

A risk management file (in accordance with ISO 14971:2019) is required for all medical devices, and usability engineering or human factors engineering (in accordance with IEC 62366-1) is required for all medical devices. The software and cybersecurity procedures listed above are only required for products with 1) software and/or firmware, and 2) wireless functionality or an access point for removable media (e.g., USB flash drive or SD card).

Even though the requirement for design controls has been in place for more than 25 years, there are still far too many design teams that struggle with understanding these requirements. Medical device regulations are complex, but design controls are the most complex process in any quality system. The reason for this is that each of the seven sub-clauses represents a mini-process that is equivalent in complexity to CAPA root cause analysis. Many companies choose to create separate work instructions for each sub-clause.

Medical Device Academy’s training philosophy is to distill processes down to discrete steps that can be absorbed and implemented quickly. We use independent forms to support each step and develop training courses with practical examples, instead of writing a detailed procedure(s). The approach we teach removes complexity from your design control procedure (SYS-008). Instead, we rely upon the structure of step-by-step forms completed at each stage of the design process.

If you are interested in design control training, Rob Packard will be hosting the 3rd edition of our Design Controls Training Webinar on Friday, August 11, 2023, @ 9:30 am EDT.

Post-market surveillance is not currently required by the FDA in 21 CFR 820, but it is required by ISO 13485:2016 in Clause 7.3.3c) (i.e., “[Design and development inputs] shall include…applicable outputs(s) of risk management”). The FDA is expected to release the plans for the transition to ISO 13485 in FY 2024, but most companies mistakenly think that the FDA does not require consideration of post-market surveillance when they are designing new devices. This is not correct. There are three ways the FDA expects post-market surveillance to be considered when you are developing a new device:

Even though the FDA does not currently require compliance with ISO 13485, the FDA does recognize ISO 14971:2019, and post-market surveillance is identified as an input to the risk management process in Clause 4.2 (see note 2), Clause 10.4, and Annex A.2.10.

You are required to update your design plan as the development project progresses. Most design and development projects take a year before the company is ready to submit a 510k submission to the FDA. Therefore, don’t worry about making your first version of the plan perfect. You have a year to make lots of improvements to your design plan. At a minimum, you should be updating your design plan during each design review. One thing that is important to capture in your first version, however, is the correct regulatory pathway for your intended markets. If you aren’t sure which markets you plan to launch in, you can select one market and add more later, or you can select a few and delete one or more later. Your design plan should identify the resources needed for the development project, and you should estimate when you expect to conduct each of your design reviews.

The requirement for design plans is stated in both Clause 7.3.1 of the ISO Standards, and Section 21 CFR 820.30b of the FDA QSR. You can make your plan as detailed as you need to, but I recommend starting simple and adding detail. Your first version of a design plan should include the following tasks:

Your testing plan must indicate which recognized standards you plan to conform with, and any requirements that are not applicable should be identified and documented with a justification for the non-applicability. The initial version of your testing plan will be an early version of your user needs and design inputs. However, you should expect the design inputs to change several times. After you receive feedback from regulators is one time you may need to make changes to design inputs. You may also need to make changes when you fail your testing (i.e., preliminary testing, verification testing, or validation testing). If your company is following “The Lean Startup” methodology, your initial version of the design inputs will be for a minimum viable product (i.e., MVP). As you progress through your iterative development process, you will add and delete design inputs based on customer feedback and preliminary testing. Your goal should be to fail early and fail fast because you don’t want to get to your verification testing and fail. That’s why we conduct a “design freeze,” prior to starting the design verification testing and design transfer activities.

Design inputs need to be requirements verified through the use of a verification protocol. If you identify external standards for each design input, you will have an easier time completing the verification activities, because verification tests will be easier to identify. Some standards do not include testing requirements, and there are requirements that do not correspond to an external standard. For example, IEC 62366-1 is an international standard for usability engineering, but the standard does not include specific testing requirements. Therefore, manufacturers have to develop their own test protocol for validation of the usability engineering controls implemented. If your company is developing a novel sterilization process (e.g., UV sterilization), you will also need to develop your own verification testing protocols. In these cases, you should submit the draft protocols to the FDA (along with associated risk analysis documentation) to obtain feedback and agreement with your testing plan. The method for obtaining written feedback and agreement with a proposed testing plan is to submit a pre-submission meeting request to the FDA (i.e., PreSTAR).

Design controls became a legal requirement in the USA in 1996 when the FDA updated the quality system regulations. At that time, the “V-diagram” was quite new and limited to software development. Therefore, the FDA requested permission from Health Canada to reprint the “Waterfall Diagram” in the design control guidance that the FDA released. Both diagrams are models. They do not represent best practices, and they do not claim to represent how the design process is done in most companies. The primary information that is being communicated by the “Waterfall Diagram” is that user needs are validated while design inputs are verified. The diagram is not intended to communicate that the design process is linear or must proceed from user needs, to design inputs, and then to design outputs. The “V-Diagram” is meant to communicate that there are multiple levels of verification and validation testing that occur, and the development process is iterative as software bugs are identified. Both models help teach design and development concepts, but neither is meant to imply legal requirements. One of the best lessons to teach design and development teams is that this is a need to develop simple tests to screen design concepts so that design concepts can fail early and fail fast–before the design is frozen. This process is called “risk control option analysis,” and it is required in clause 7.1 of ISO 14971:2019.

Design outputs are drawings and specifications. Ensure you keep them updated and control the changes. When you finally approve the design, this is approval of your design outputs (i.e., selection of risk control options). The final selection of design outputs or risk control measures is often conducted as a formal design review meeting. The reason for this is that the cost of design verification is significant. There is no regulatory or legal requirement for a “design freeze.” In fact, there are many examples where changes are anticipated but the team decides to proceed with the verification testing anyway. The best practice developed by the medical device industry is to conduct a “design freeze.” The design outputs are “frozen” and no further changes are permitted. The act of freezing the design is simply intended to reduce the business risk of spending money on verification testing twice because the design outputs were changed during the testing process. If a device fails testing, it will be necessary to change the design and repeat the testing, but if every person on the design team agrees that the need for changes is remote and the company should begin testing it is less likely that changes will be made after the testing begins.

Design transfer is not a single event in time. Transfer begins with the release of your first drawing or specification to purchasing and ends with the commercial release of the product. The most common example of a design transfer activity is the approval of prototype drawings as a final released drawing. This is common for molded parts. Several iterations of the plastic part might be evaluated using 3D printed parts and machined parts, but in order to consistently make the component for the target cost an injection mold is typically needed. The cost of the mold may be $40-100K, but it is difficult to change the design once the mold is built. The lead time for injection molds is often 10-14 weeks. Therefore, a design team may begin the design transfer process for molded parts prior to conducting a design freeze. Another component that may be released earlier as a final design is a printed circuit board (PCB). Electronic components such as resistors, capacitors, and integrated circuits (ICs) may be available off-the-shelf, but the raw PCB has a longer lead time and is customized for your device.

Design verification testing requires pre-approved protocols and pre-defined acceptance criteria. Whenever possible, design verification protocols should be standardized instead of being project-specific. Information regarding traceability to the calibrated equipment identification and test methods should be included as a variable that is entered manually into a blank space when the protocol is executed. The philosophy behind this approach is to create a protocol once and repeat it forever. This results in a verification process that is consistent and predictable, but it also eliminates the need for review and approval of the protocol for each new project. Standardized protocols do not need to specify a vendor or dates for the testing, but you might consider documenting the vendor(s) and duration of the testing in your design inputs to help with project management and planning. You might also want to use a standardized template for the format and content of your protocol and report. The FDA provides a guidance document specifically for the report format and content for non-clinical performance testing.

Design validation is required to demonstrate that the device meets the user’s and patient’s needs. User needs are typically the indications for use–including safety and performance requirements. Design validation should be more than bench testing. Ensure that animal models, simulated anatomical models, finite element analysis, and human clinical studies are considered. One purpose of design validation is to demonstrate performance for the indications for use, but validating that risk controls implemented are effective at preventing use-related risks is also important. Therefore, human factors summative validation testing is one type of design validation. Human factors testing will typically involve simulated use with the final version of the device and intended users. Validation testing usually requires side-by-side non-clinical performance testing with a predicate device for a 510k submission, while CE Marking submissions typically require human clinical data to demonstrate safety and performance.

FDA pre-market notification, or 510k submission, is the most common type of regulatory approval required for medical devices in the USA. FDA submissions are usually possible to submit earlier than other countries, because the FDA does not require quality system certification or summary technical documents, and performance testing data is usually non-clinical benchtop testing. FDA 510k submissions also do not require submission of process validation for manufacturing. Therefore, most verification and validation is conducted on “production equivalents” that were made in small volume before the commercial manufacturing process is validated. The quality system and manufacturing process validation may be completed during the FDA 510k review.

Design reviews should have defined deliverables. We recommend designing a form for documenting the design review, which identifies the deliverables for each design review. The form should also define the minimum required attendees by function. Other design review attendees should be identified as optional—rather than required reviewers and approvers. If your design review process requires too many people, this will have a long-term impact upon review and approval of design changes.

The only required design review is a final design review to approve the commercial release of your product. Do not keep the DHF open after commercial release. All changes after that point should be under production controls, and changes should be documented in the (DMR)/Technical File (TF). If device modifications require a new 510k submission, then you should create a new design project and DHF for the device modification. The new DHF might have no changes to the user needs and design inputs, but you might have minor changes (e.g., a change in the sterilization method requires testing to revised design inputs).

Within 30 days of initial product distribution in the USA, you are required to register your establishment with the FDA. Registration must be renewed annually between October 1 and December 31, and registration is required for each facility. If your company is located outside the USA, you will need an initial importer that is registered and you will need to register before you can ship the product to the USA. Non-US companies must also designate a US Agent that resides in the USA. At the time of FDA registration, your company is expected to be compliant with all regulations for the quality system, UDI, medical device reporting, and corrections/removals.

One of the required outputs of your final design review is your DMR Index. The DMR Index should perform a dual function of also meeting technical documentation requirements for other countries, such as Canada and Europe. A Technical File Index, however, includes additional documents that are not required in the USA. One of those documents is your post-market surveillance plan and the results of post-market surveillance. That post-market surveillance is an input to your design process for the next generation of products. Any use errors, software bugs, or suggestions for new functionality should be documented as post-market surveillance and considered as potential inputs to the design process for future design projects.