CAPA – Corrective/Preventative Action

What is a CAPA? How do you evaluate the need to open a new CAPA, and who should be assigned to work on it when you do?

What is a CAPA?

“CAPA” is the acronym for corrective action and preventive action. It’s a systematic process for identifying the root cause of quality problems and identifying actions for containment, correction, and corrective action. In the special case of preventive actions, the actions taken prevent quality problems from ever happening, while the corrective actions prevent quality problems from happening again. The US FDA requires a CAPA procedure, and an inadequate CAPA process is the most common reason for FDA 483 inspection observations and warning letters. When I teach courses on the CAPA process, 100% of the people can tell me what the acronym CAPA stands for. If everyone understands what a CAPA is, why is the CAPA process the most common source of FDA 483 inspection observations and auditor nonconformities?

Most of the 483 inspection observations identify one of the following seven problems:

- the procedure is inadequate

- records are incomplete

- actions planned did not include corrections

- actions planned did not include corrective actions

- actions planned were not taken or delayed

- training is inadequate

- actions taken were not effective

CAPA Resources – Procedures, Forms, and Training

Medical device companies are required to have a CAPA procedure. Medical Device Academy offers a CAPA procedure for sale as an individual procedure or as part of our turnkey quality systems. Purchase of the procedure includes a form for your CAPA records and a CAPA log for monitoring and measuring the CAPA process effectiveness. You can also purchase our risk-based CAPA webinar, which the turnkey quality system includes.

What’s special about preventive action?

I completed hundreds of audits of CAPA processes over the years. Surprisingly, this seems to be a process with more variation from company to company than almost any other process I review. This also seems to be a significant source of non-conformities. In the ISO 13485 Standard, clauses 8.5.2 (Corrective Action) and 8.5.3 (Preventive Action) have almost identical requirements. Third-party auditors, however, emphasize that these are two separate clauses. I like to refer to certification body auditors as purists. Although certification body auditors acknowledge that companies may implement preventive actions as an extension of corrective action, they also expect to see examples of strictly preventive actions.

You may be confused between corrective actions and preventive actions, but there is an easy way to avoid confusion. Ask yourself one question: “Why did you initiate the CAPA?” If the reason was: 1) a complaint, 2) audit non-conformity, or 3) rejected components—then your actions are corrective. You can always extend your actions to include other products, equipment, or suppliers that were not involved if they triggered the CAPA. However, for a CAPA to be purely preventive in nature, you need to initiate the CAPA before complaints, non-conformities and rejects occur.

How do you evaluate the need to open a CAPA?

If the estimated risk is low and the probability of occurrence is known, then alert limits and action limits can be statistically derived. These quality issues are candidates for continued trend analysis—although the alert or action limits may be modified in response to an investigation. If the trend analysis results in identifying events that require action, then that is the time when a formal CAPA should be opened. No formal CAPA is needed if the trend remains below your alert limit.

If the estimated risk is moderate or the probability of occurrence is unknown, then a formal CAPA should be considered. Ideally, you can establish a baseline for the occurrence and demonstrate that frequency decreases upon implementing corrective actions. If you can demonstrate a significant drop in frequency, this verifies the effectiveness of actions taken. If you need statistics to show a difference, then your actions are not effective.

A quality improvement plan may be more appropriate if the estimated risk is high or multiple causes require multiple corrective actions. Two clauses in the Standard apply. Clause 5.4.2 addresses the planning of changes to the Quality Management System. For example, if you correct problems with your incoming inspection process—this addresses 5.4.2. Clause 7.1 addresses the planning of product realization. For example, if you correct problems with a component specification where the incoming inspection process is not effective, this addresses 7.1. The plan could be longer or shorter Depending on the number of contributing causes and the complexity of implementing solutions. If implementing corrective action takes more than 90 days, you might consider the following approach.

Step 1 – open a CAPA

Step 2 – identify the initiation of a quality plan as one of your corrective actions

Step 3 – close the CAPA when your quality plan is initiated (i.e., – documented and approved)

Step 4 –verify effectiveness by reviewing the progress of the quality plan in management reviews and other meeting forums…you can cross-reference the CAPA with the appropriate management review meeting minutes in your effectiveness section

If the corrective action required is installing and validating new equipment, the CAPA can be closed as soon as a validation plan is created. The effectiveness of the CAPA is verified when the validation protocol is successfully implemented, and a positive conclusion is reached. The same approach also works for implementing software solutions to manage processes better. The basic strategy is to start long-term improvement projects with the CAPA system but monitor the status of these projects outside the CAPA system.

Best practices would be implementing six-sigma projects with formal charters for each long-term improvement project.

NOTE: I recommend closing CAPAs when actions are implemented and tracking the effectiveness checks for CAPAs as a separate quality system metric. If closure takes over 90 days, the CAPA should probably be converted to a Quality Plan. This is NOT intended to be a “workaround” to give companies a way to extend CAPAs that are not making progress on time.

Who should be assigned to work on a CAPA?

Personnel in quality assurance are usually assigned to CAPAs, while managers in other departments are less frequently assigned to CAPAs. This is a mistake. Each process should have a process owner, who should be assigned to the root cause investigation, develop a CAPA plan, and manage the planned actions. If the manager is not adequately trained, someone from the quality assurance department should use this as an opportunity to conduct on-the-job training to help them with the CAPA–not do the work for them. This will increase the number of people in the company with CAPA competency. This will also ensure that the process owner takes a leadership role in revising and updating procedures and training on the processes that need improvement. Finally, the process will teach the process owner the importance of using monitoring and measuring the process to identify when the process is out of control or needs improvement. The best practice is to establish a CAPA Board to monitor the CAPA process, expedite actions when needed, and ensure that adequate resources are made available.

What is a root cause investigation?

If you are investigating the root cause of a complaint, people will sample additional records to estimate the frequency of the quality issue. I describe this as investigating the depth of a problem. The FDA emphasizes the need to review other product lines, or processes, to determine if a similar problem exists. I describe this as investigating the breadth of a problem. Most companies describe actions taken on other product lines and/or processes as “preventive actions.” This is not always accurate. If a problem is found elsewhere, actions taken are corrective. If potential problems are found elsewhere, actions taken are preventive. You could have both types of actions, but most people incorrectly identify corrective actions as preventive actions.

Another common mistake is to characterize corrections as corrective actions.

The most striking difference between companies seems to be the number of CAPAs they initiate. There are many reasons, but the primary reason is the failure to use a risk-based approach to CAPAs. Not every quality issue should result in the initiation of a formal CAPA. The first step is to investigate the root cause of a quality issue. The FDA requires that the root cause investigation is documented, but if you already have an open CAPA for the same root cause…DO NOT OPEN A NEW CAPA!!!

What should you do if you do not have a CAPA open for the root cause you identify?

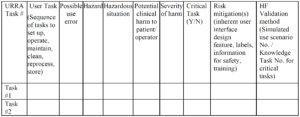

The image below gives you my basic philosophy.

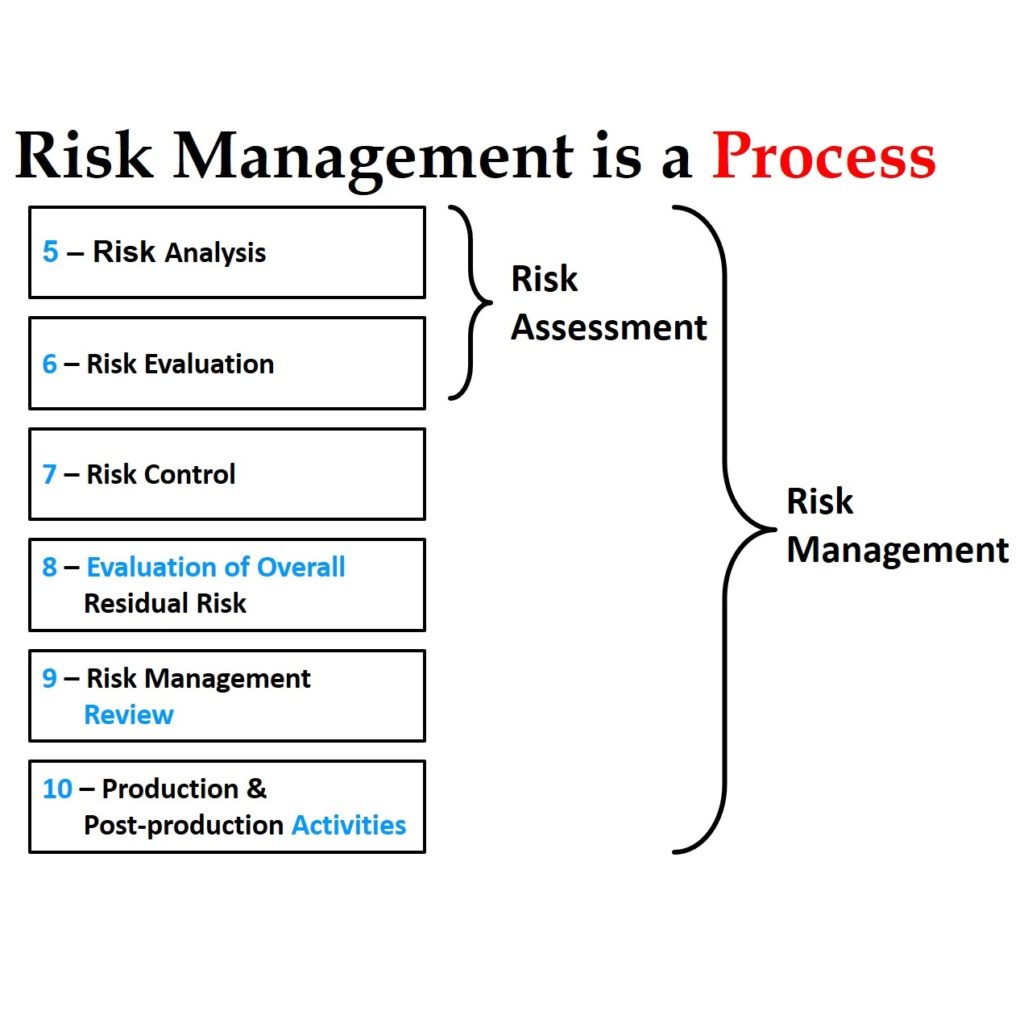

Most CAPA investigations document the estimated probability of occurrence of a quality issue. This is only half of the necessary risk analysis I describe below. Another aspect of an investigation is documenting the severity of potential harm resulting from the quality issue. If a quality issue affects customer satisfaction, safety, or efficacy, the severity is significant. Risk is the product of severity and probability of occurrence.

Most CAPA investigations document the estimated probability of occurrence of a quality issue. This is only half of the necessary risk analysis I describe below. Another aspect of an investigation is documenting the severity of potential harm resulting from the quality issue. If a quality issue affects customer satisfaction, safety, or efficacy, the severity is significant. Risk is the product of severity and probability of occurrence.

How much detail is needed in your CAPAs?

One of the most common reasons for an FDA 483 inspection observation related to CAPAs is the lack of detail. You may be doing all the planned tasks but must document your activity. Investigations will often include a lot of detail identifying how the root cause was identified, but you need an equal level of detail for planned containment, corrections, corrective actions, and effectiveness checks. Who is responsible, when will it be completed, how will it be done, what will the records be, and how will you monitor progress? Make sure you include copies of records in the CAPA file as well because this eliminates the need for inspectors and auditors to request additional records that are related to the CAPA. Ideally, the person reviewing the CAPA file will not need to request any additional records. For example, a copy of the revised process procedure, a copy of training records, and a copy of graphed metrics for the process are frequently missing from a CAPA file, but auditors will request this information to verify all actions were completed and that the CAPA is effective.

What is the difference between corrections and corrective actions?

Every nonconformity identified in the original finding requires correction. By reviewing records, FDA inspectors and auditors will verify that each correction was completed. In addition, several new nonconformities may be identified during the investigation of the root cause. Corrections must be documented for the newly found nonconformities as well. Corrective actions are actions you take to prevent new nonconformities from occurring. Examples of the most common corrective actions include: revising procedures, revising forms, retraining personnel, and creating new process metrics to monitor and measure the effectiveness of a process. Firing someone who did not follow a procedure is not a corrective action. Better employee recruiting, onboarding, and management oversight should prevent employees from making serious mistakes. The goal is to have a near-perfect process that identifies human error rather than a near-perfect employee that has to compensate for weak processes.

Implementing timely corrective actions

Every correction and corrective action in your CAPA plan should include a target completion date, and a specific person should be assigned to each task. Once your plan is approved, you need a mechanism for monitoring the on-time completion of each task. There should be top management or a CAPA board this is responsible for reviewing and expediting CAPAs. If CAPAs are being completed on-schedule, regular meetings are short. If CAPAs are behind schedule, management or the CAPA board needs authority and responsibility to expedite actions and make additional resources available when needed. Identifying lead and lag metrics is essential to manage the CAPA process successfully–and all other quality system processes.

What is an effectiveness check?

Implementation of actions and effectiveness of actions is frequently confused. An action was implemented when the action you planned was completed. Usually, this is documented with the approval of revised documents and training records. The effectiveness of actions is more challenging to demonstrate, and therefore it is critical to identify lead and lag metrics for each process. The lead metrics are metrics that measure the routine activities that are necessary for a process, while the lag metrics measure the results of activities. For example, monitoring the frequency of cleaning in a controlled environment is a lead metric, while monitoring the bioburden and particulates is a lag metric. Therefore, effectiveness checks should be quantitative whenever possible. Your effectiveness is weak if you need to use statistics to show a statistical difference before and after implementing your CAPA plan. If a graph of the process metrics is noticeably improved after implementing your CAPA plan, then the effectiveness is strong.

About Your Instructor

Rob Packard is a regulatory consultant with ~25 years of experience in the medical device, pharmaceutical, and biotechnology industries. He is a graduate of UConn in Chemical Engineering. Rob was a senior manager at several medical device companies—including the President/CEO of a laparoscopic imaging company. His Quality Management System expertise covers all aspects of developing, training, implementing, and maintaining ISO 13485 and ISO 14971 certifications. From 2009 to 2012, he was a lead auditor and instructor for one of the largest Notified Bodies. Rob’s specialty is regulatory submissions for high-risk medical devices, such as implants and drug/device combination products for CE marking applications, Canadian medical device applications, and 510(k) submissions. The most favorite part of his job is training others. He can be reached via phone at 802.281.4381 or by email. You can also follow him on YouTube, LinkedIn, or Twitter.

CAPA – Corrective/Preventative Action Read More »