FDA eSTAR v5.5 – What’s new?

This blog provides a deep dive into the newest version of the FDA eSTAR, version 5.5, released on February 12, 2025.

Why did the FDA release the new eSTAR version as v5.5 instead of v6.0?

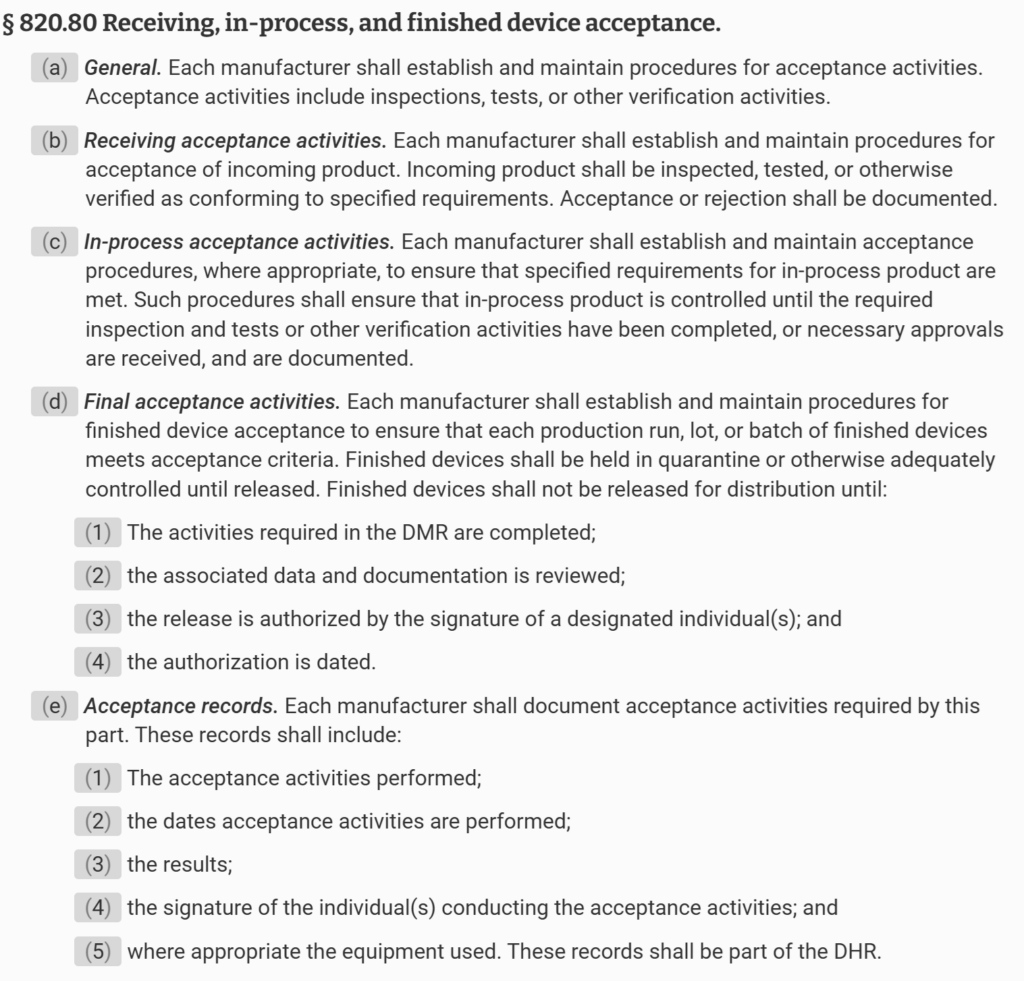

A major version update consists of policy changes, regulatory changes, or major changes to the template and will be denoted by a major version number increment (e.g. 5.4 to 6.0). A minor version update will consist of other changes and will be denoted by a minor version number increment (e.g. 5.4 to 5.5). If there are policy or regulatory changes, a new major version of the eSTAR is made before the implementation date, and the previous version of the eSTAR is removed. As an example, the FDA updated v4.3 to v4.4 to enable PMA content, updates to the international pilot of the eSTAR with Health Canada, and implementation of cybersecurity documentation requirements are considered major changes that trigger the need for a major version update (i.e., 5.0) instead of a minor version update (i.e., 4.4). These changes apply to the IVD eSTAR and the non-IVD eSTAR. If you are generally unfamiliar with the FDA eSTAR, please visit our 510k course page.

What is the deadline for using v5.5?

Version 5.4 of the FDA eSTAR, both the nIVD and IVD versions, may continue to be used until v6.0 is eventually released. In fact, any v5.x may be used until v6.0 is released. Any submissions that are submitted with an expired version (v4.x) of the eSTAR will be rejected. If you have already uploaded information to an older version of the template, you will need to scroll to the bottom of the eSTAR and export the data to an HTML file. Then you import the HTML file into the newer version of the eSTAR. Any attachments you made to the older version of the template will not be exported, and you will have to attach all of the attachments to the new template.

PMA content is enabled in the new FDA eSTAR

Previous versions of the FDA eSTAR included the functionality for premarket approval (PMA) submissions, but in version 5.0 the FDA finally enabled this functionality. 510k submissions have three types: 1) Traditional, 2) Abbreviated, and 3) Special. PMA submissions also have different types. There are two types of PMA submissions for a new device: traditional and modular. Unfortunately, the FDA eSTAR is not intended for PMAs using the modular approach. For Class 3 devices, the FDA has more stringent controls over changes than Class 1 and 2 devices. Therefore, a PMA supplement is required for the following types of changes to PMA-approved devices:

- new indications for use;

- labeling changes;

- facility changes for manufacturing or packaging;

- changes in manufacturing methods;

- changes in quality control procedures;

- changes in sterilization procedures;

- changes in packaging;

- changes in the performance or design specifications, and

- extension of the expiration date.

There are several types of PMA supplements, but only three types of supplements can use the FDA eSTAR: 1) Panel-Track, 2) 180-Day, and 3) Real Time. To determine which type of PMA supplement you should use, the FDA published guidance for modifications to devices subject to the premarket approval process.

PMA Content

The following sections in the FDA eSTAR are specific to PMA submission content requirements:

- Quality Management System Information

- Facility Information

- Post-Market Study (PMS) Plans

- Attach an exclusion statement, or an Environmental Assessment Report in accordance with 21 CFR 814.20(b)(11)

Health Canada is conducting a pilot with the FDA eSTAR

Health Canada’s FDA eSTAR pilot is now full with a total of 10 participants (originally only 9 were planned). The pilot will test the use of eSTAR for applications submitted to Health Canada. The results of the pilot should be complete soon, and then we expect an extension of the pilot to a broader number of applicants. We heard rumors that the HC eSTAR was overly complicated. Hopefully, future versions are simplified.

Were there any changes to the EMC testing section?

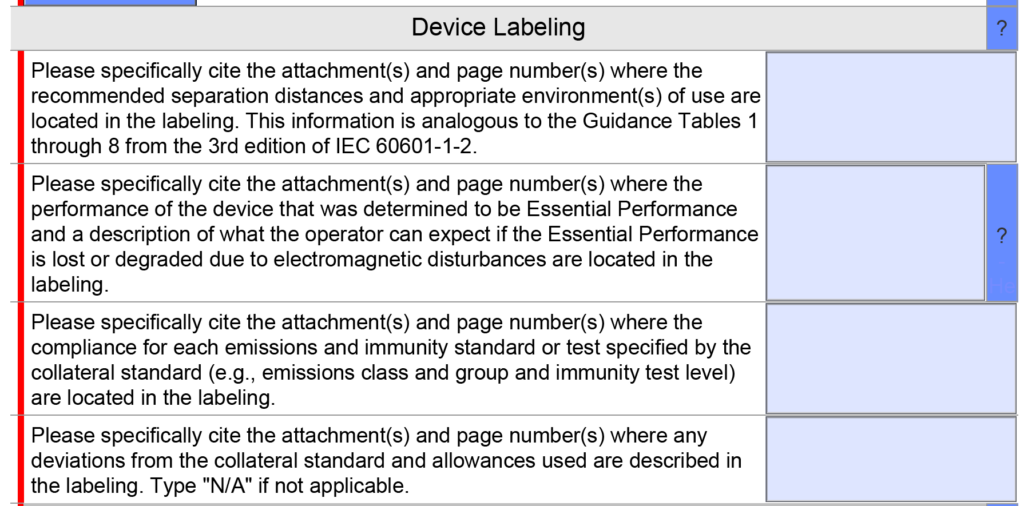

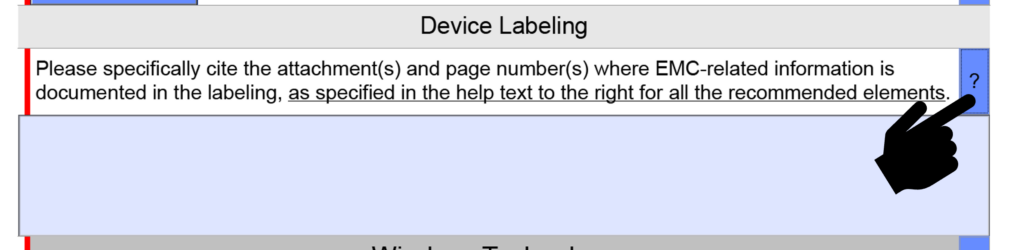

EMC Labeling questions were consolidated into a single question instead of four because only one citation is usually provided in this section. A copy of the older version is provided below.

The updated version 5.0 is shown below and has only one question, but the help text was changed.

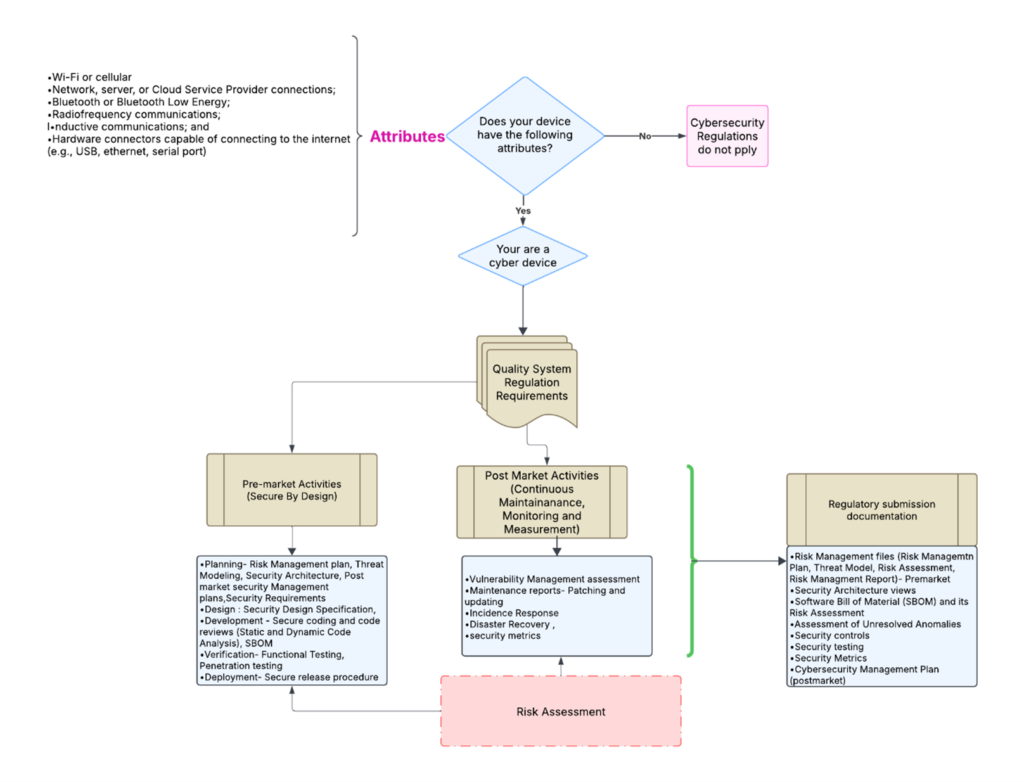

Does the FDA eSTAR now require more cybersecurity documentation?

Bhoomika Joyappa updated our cybersecurity work instruction (WI-007) to address the updated FDA guidance for cybersecurity documentation. The revisions were completed earlier this month, and you can purchase the updated templates on our website. We have also been telling our subscribers to anticipate a significant revision to the FDA eSTAR  template when this happens. The release of the updated eSTAR version took a little over two months, and the change resulted in a three-page section dedicated to cybersecurity documentation. The previous versions of the template included a requirement for documentation of cybersecurity risk management and a cybersecurity management plan/plan for continuing support. The following documents must be attached in this section if cybersecurity applies to your device:

template when this happens. The release of the updated eSTAR version took a little over two months, and the change resulted in a three-page section dedicated to cybersecurity documentation. The previous versions of the template included a requirement for documentation of cybersecurity risk management and a cybersecurity management plan/plan for continuing support. The following documents must be attached in this section if cybersecurity applies to your device:

- risk management – report (attach)

- risk management – threat model (attach)

- list of threat methodology (text box)

- verification that the threat model documentation includes (yes/no dropdown):

- global system view

- Multi-patient harm view

- Updateability/patchability view

- Security use case views

- cybersecurity risk assessment (attach)

- page numbers where methodology and acceptance criteria are documented (text box)

- verification that the risk assessment avoids using probability for the likelihood assessment and use exploitability instead (yes/no dropdown)

- software bill of materials or SBOM (attach)

- software level of support and end-of-support date for each software component (attach)

- operating system and version used (text box)

- safety and security assessment of vulnerabilities (attach)

- assessment of any unresolved anomalies (attach)

- data from monitoring cybersecurity metrics (attach)

- information about security controls (attach)

- page numbers where each security control is addressed (text box):

- Authentication controls

- Authorization controls

- Cryptography controls

- Code, data, and execution integrity controls

- Confidentiality controls

- Event detection and logging controls

- Resiliency and recovery controls

- Firmware and software update controls

- architecture views (attach)

- cybersecurity testing (attach)

- page numbers where cybersecurity labeling is provided (text box)

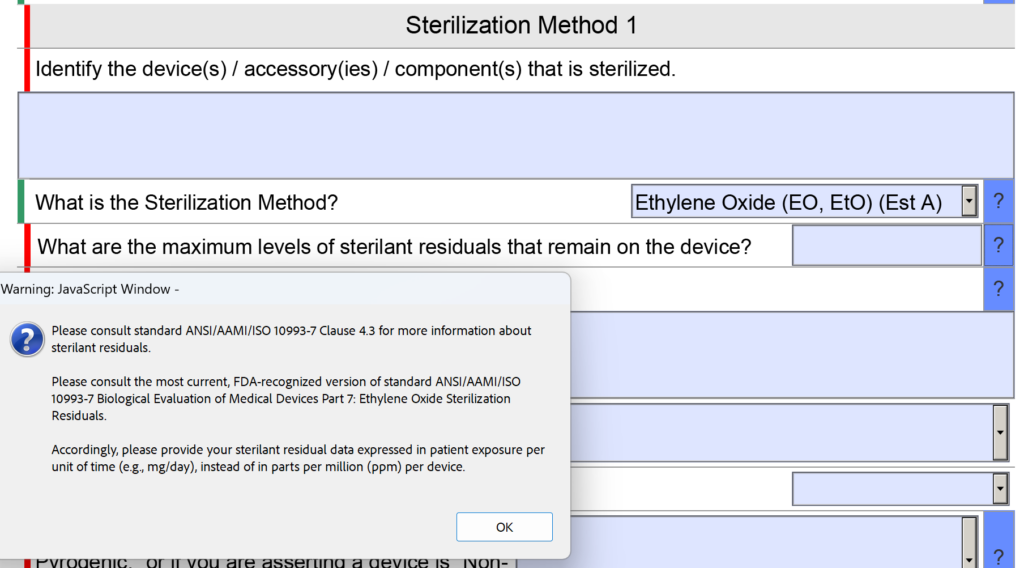

Sterility section changes include an updated question on EO residuals

In the sterility section of the FDA eSTAR there was a question about sterilant residues. Specifically, the question was “What are the maximum levels of sterilant residual that remain on the device?” The space provided for entering the information was small as well.

Now the question is reworded to: “What are the maximum levels of sterilant residuals that remain on the device, and what is your explanation for why those levels are acceptable for the device type and the expected duration of patient contact?” No change was made to the help text for this question.

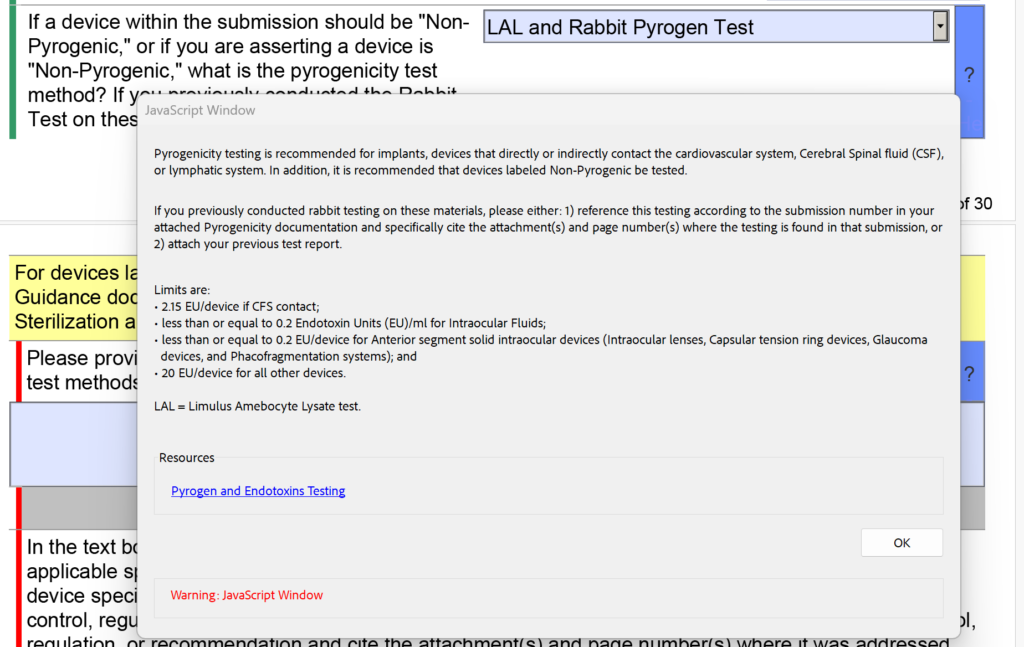

In addition to the changes in the sterility section regarding EO residuals, the FDA also modified the dropdown menu and the help text for pyrogenicity testing. There were options for “LAL” and “Rabbit Test” separately, but now these are combined into “LAL and Rabbit Pyrogen Test.” In addition, the following help text was added: “If you previously conducted rabbit testing on these materials, please either: 1) reference this testing according to the submission number in your attached Pyrogenicity documentation and specifically cite the attachment(s) and page number(s) where the testing is found in that submission, or 2) attach your previous test report.”

What is the deadline for using v5.0?

Many clients say that they get an error message when they try to open the FDA eSTAR template. This is because they are opening the eSTAR from a PDF viewer instead of Adobe Acrobat Pro.

Some people want to save money by using the free Adobe Acrobat Reader software instead, but this will not allow you to complete the eSTAR properly. Therefore, the FDA added a Popup message if Adobe Acrobat Reader is used.

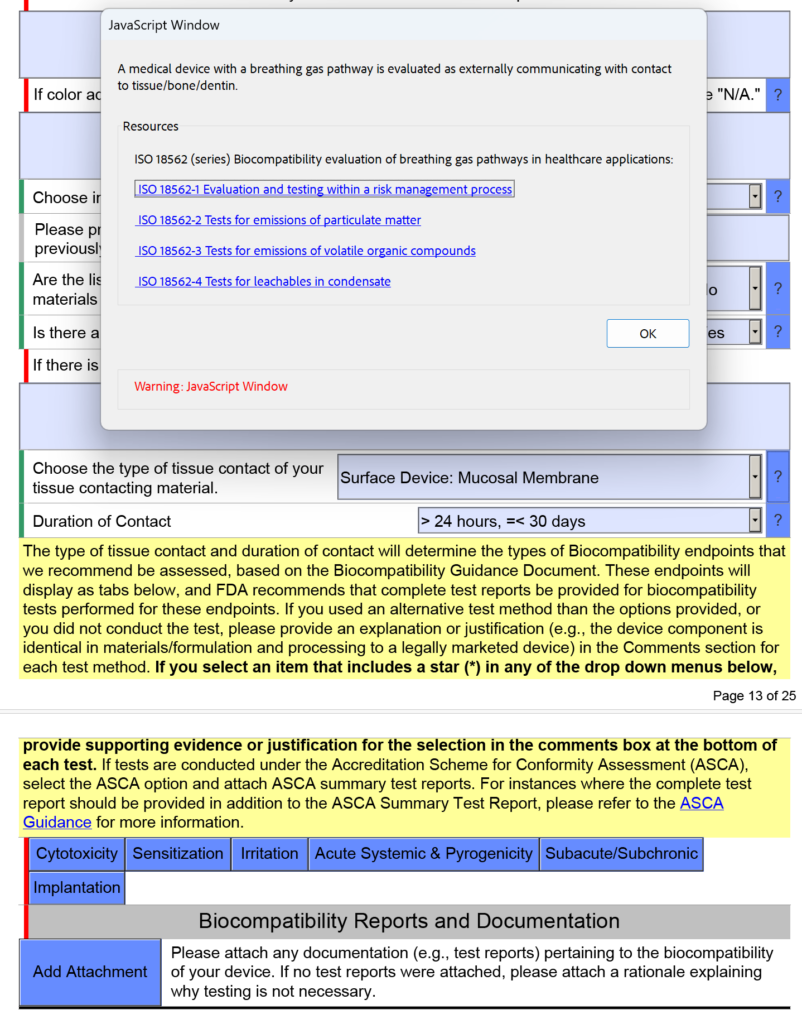

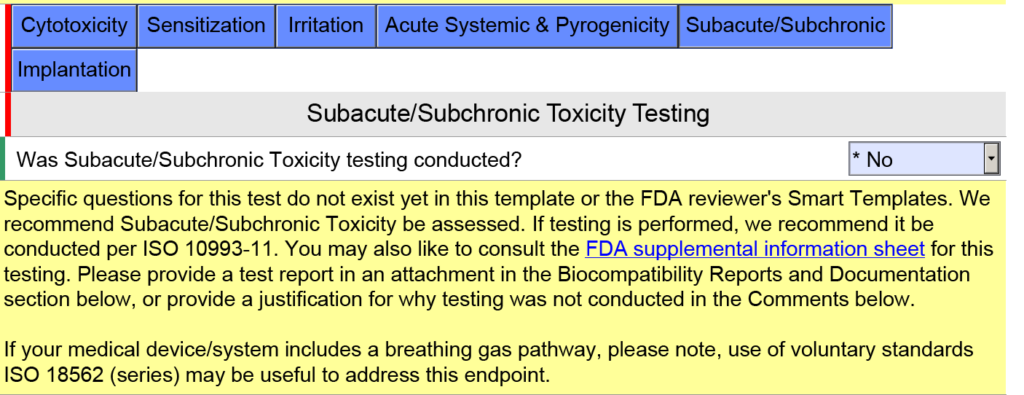

How are devices with a breathing gas pathway evaluated for biocompatibility?

In the screen capture below, I have intentionally selected “Surface Device: Mucosal Membrane” as the type of tissue contact for a breathing gas pathway device because the device will have a mouthpiece placed in your mouth (i.e., mucosal membrane). This is a common mistake. In version 5.0 of the FDA eSTAR, the FDA clarifies that these devices should be evaluated as “externally communicating” and the tissue contact is “tissue/bone/dentin.” Specifically, the tissue contact is the lungs. For this reason, the FDA added the help text shown below in the JavaScript Window regarding the applicability of ISO 18562-1, -2, -3, and -4.

Additional questions and guidance will appear when you click on the individual blue boxes shown above. For the blue box labeled “Subacute/Subchronic,” you will find additional help text regarding the ISO 18562 standards. Similar help text is found when you click the blue box labeled “Acute Systemic & Pyrogenicity.”

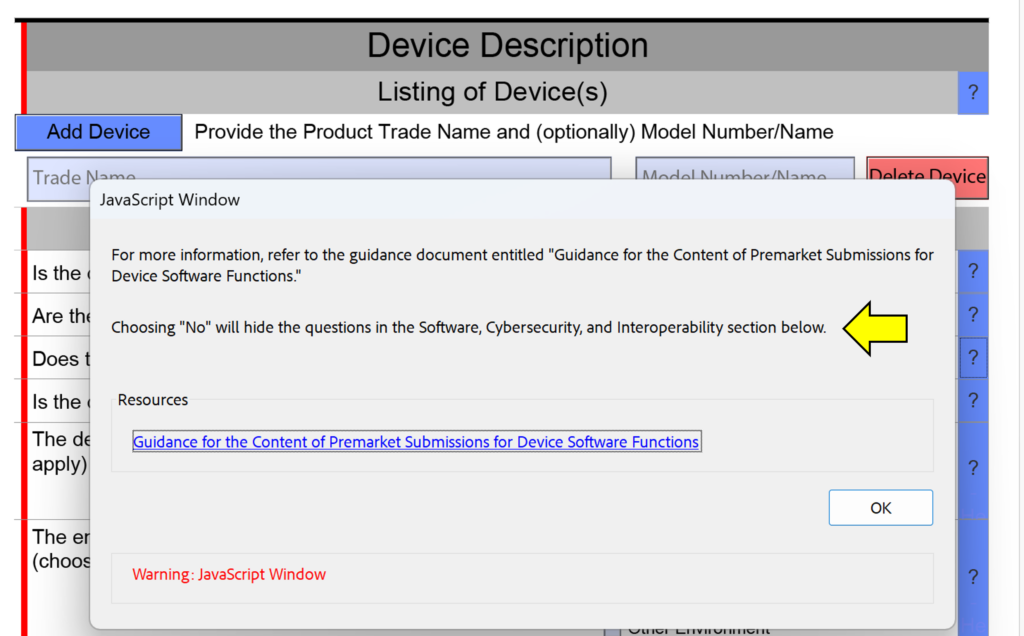

What is a cross-section change reminder?

One of the minor changes made in this FDA eSTAR version is the addition of “cross-section change reminders” to the help text in the device description section. This is not meant to help you avoid answering questions in your submission, because if you are missing a section of the submission because you answered “No” instead of “Yes” the FDA reviewer will identify this error during the Technical Review process. This will result in your submission being placed on hold and the review time clock will be reset to zero days when you resubmit with the corrections made. The screen capture below shows an example of one of these cross-section change reminders.

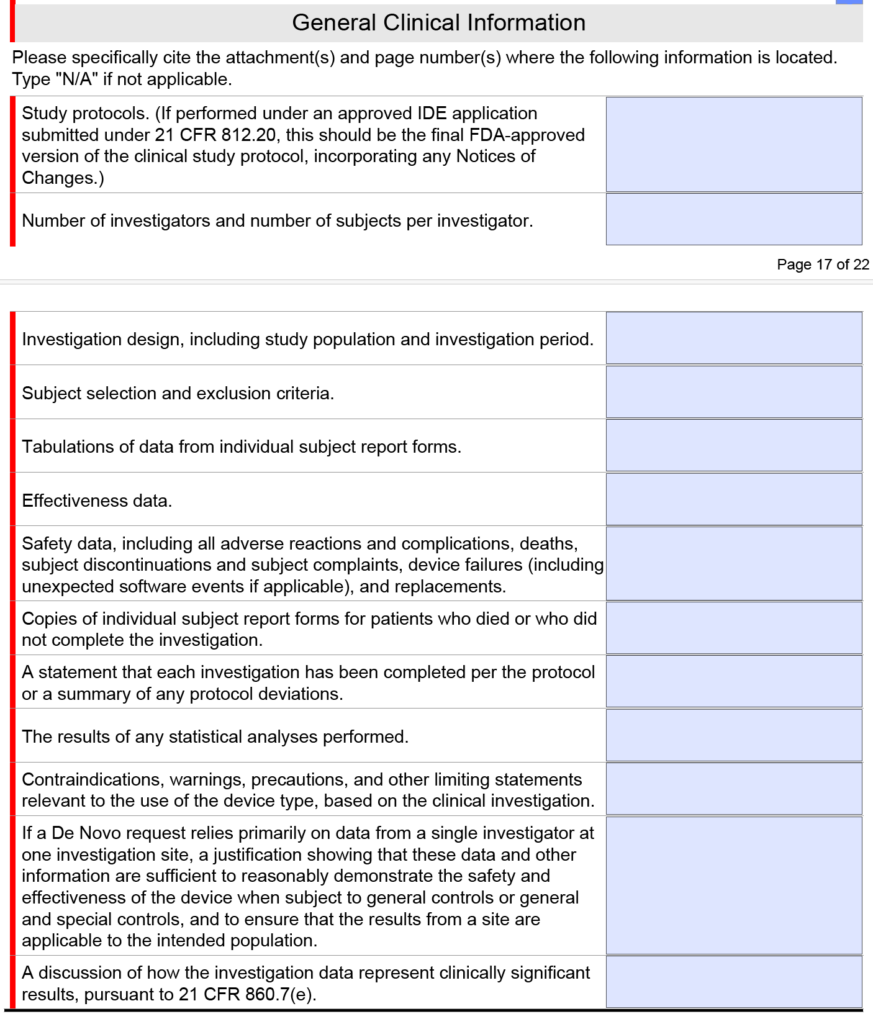

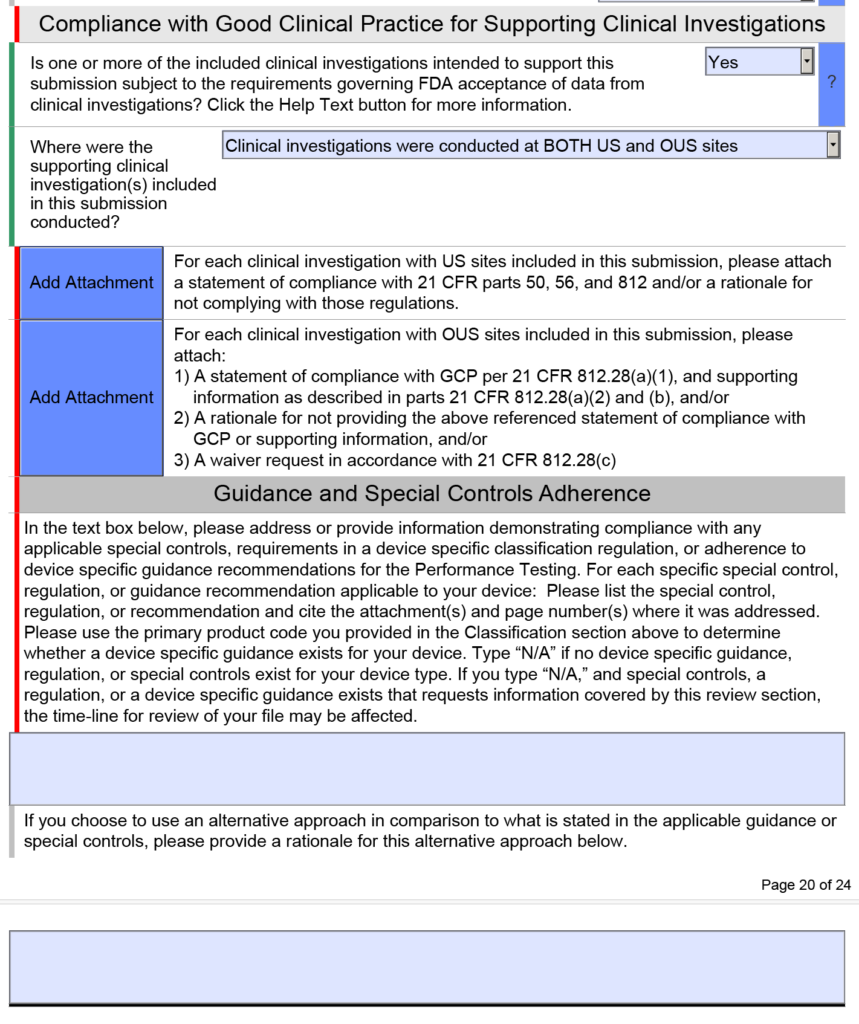

What changes were made to the clinical testing section of the FDA eSTAR?

The clinical testing section will now display when using PDF-XChange Editor, but we recommend only using Adobe Acrobat Pro to edit the FDA eSTAR. This change is a bug fix, and it is specific to the nIVD eSTAR. The IVD eSTAR and the nIVD eSTAR both include a clinical testing section within the performance testing section, but the performance testing section is found in the FDA eSTAR before the electrical safety and EMC testing section, while the performance testing section is found after the electrical safety and EMC testing section. If your company is planning to submit clinical data in a future FDA submission, we have the following recommendations:

- watch the CDRH Learn webinars on the topic of 21 CFR 812

- conduct a pre-submission teleconference to ask questions about your clinical study protocol before IRB submission or ethics review board submission

- before you submit the pre-sub meeting request, look at what general clinical information the FDA wants for a De Novo or PMA submission in the FDA eSTAR

Note: The clinical section shown above is only found in the FDA eSTAR if you select a De Novo or PMA submission. If you submit a 510k submission with clinical data, the clinical section will be abbreviated as shown below.

FDA eSTAR v5.5 – What’s new? Read More »

As the Marketing Lead at BW&CO, Alexina holds a Bachelor of Business Administration in Marketing from the University of Houston. With a deep understanding of the grant funding landscape, she drives strategic marketing initiatives that elevate BW&CO’s brand and reach. Fluent in both English and French, Alexina excels at creating and executing campaigns that connect with diverse audiences. Her expertise includes developing content strategies, managing digital marketing efforts, and conducting market research to support business growth.

As the Marketing Lead at BW&CO, Alexina holds a Bachelor of Business Administration in Marketing from the University of Houston. With a deep understanding of the grant funding landscape, she drives strategic marketing initiatives that elevate BW&CO’s brand and reach. Fluent in both English and French, Alexina excels at creating and executing campaigns that connect with diverse audiences. Her expertise includes developing content strategies, managing digital marketing efforts, and conducting market research to support business growth.