Data Hazards for SaMD and SiMD

What are data hazards?

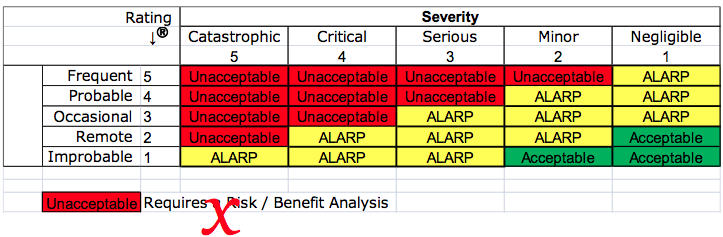

Data hazards occur when there is missing data, incorrect data, or a delay in data delivery to a database or user interface. This can occur with both software as a medical device (SaMD) and software in a medical device (SiMD). Missing data, incorrect data, and delays in data delivery cannot cause physical harm to a patient or user. Therefore, many medical device and IVD manufacturers state in their risk management file that their device or IVD has low risk or no risk. This is an incorrect software risk analysis because failure to meet software data or database requirements results in a hazardous situation, such as 1) an incorrect diagnosis or treatment, or 2) a delay in diagnosis or treatment. These hazardous situations can compromise the standard of care at best, or at worst, hazardous situations can result in physical harm–including death.

Where do you document these hazards?

Data hazards are documented in your software risk management file, but the data hazards are referenced in multiple documents. Usually data hazards will be referenced in a software hazard identification, the software risk analysis, software verification and validation test cases, and the software risk management report. Security risk assessments will also identify potential data hazards resulting from cybersecurity vulnerabilities that could be exploited.

How do you identify data hazards?

IEC 62304 is completely useless for the purpose of identifying data hazards. In Clause 5.2.2 of the standard for the software life-cycle process, the only examples of data definition and database requirements provided are form, fit, and function. IEC/TIR 80002-1, Guidance on the application of ISO 14971 to medical device software, is extremely useful. Specifically, in Table B1 the following potential data hazards are identified:

- Mix-up of Data such as:

- Associating data with the wrong patient

- Associating the wrong device/instrument with a patient

- Associating measurements with the wrong analyte

- Loss of data resulting from events such as:

- Connectivity failure or Quality of Service (QoS) issues

- Incorrect data acquisition timing or sampling rates (i.e., measurement)

- Capacity limitations during peak loads

- Missing data fields (i.e., incorrect database configuration or database mapping)

- Modification of data caused by:

- Data entry errors during manual entry

- Automated preventive maintenance

- Reset of data

- Rounding of data

- Averaging of data

Patient data also presents a security risk. Access to data must be controlled for data entry, viewing, and editing. Other potential causes of data integrity issues include power loss, division by zero, overflow/underflow, floating point rounding, improper range/bounds checking, off-by-one, hardware failure, timing, and watch-dog time outs. In Table B2 the guidance provides additional examples of causes and risk control measures are recommended for each cause.

Data hazards associated with artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML)

There are also data hazards associated with AI/ML software. When an algorithm is developed there is a potential for improving the algorithm or making the algorithm worse. There is always a data bias resulting from the patient population selected for data collection and the clinical users that assign a ground truth for that data. Sometimes the data entered is subjective or qualitative data rather than objective, quantitative data. The sequence or timing of data collection can also impact the validity of data used for training an AI algorithm. AAMI CR 34971:2023 is a Guide on the Application of ISO 14971 to Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence. That guidance identifies additional hazards associated with data and databases.

How are these hazards addressed in software requirements?

In IEC 62304, Clause 5.2.2, lists the content for twelve different software requirements (i.e., items A-L):

- a) functional and capability requirements;

- b) SOFTWARE SYSTEM inputs and outputs;

- c) interfaces between the SOFTWARE SYSTEM and other SYSTEMS;

- d) software-driven alarms, warnings, and operator messages;

- e) SECURITY requirements;

- f) user interface requirements implemented by software;

- g) data definition and database requirements;

- h) installation and acceptance requirements of the delivered MEDICAL DEVICE SOFTWARE at the operation and maintenance site or sites;

- i) requirements related to methods of operation and maintenance;

- j) requirements related to IT-network aspects;

- k) user maintenance requirements; and

- l) regulatory requirements.

These software requirements may overlap, because any specific cause of failure can result in multiple types of software hazards. For example, a loss of connectivity can result in mix-up of data, incomplete data, or modification of the data. Therefore, to ensure your software design is safe, you must carefully analyze software risks and evaluate as many test cases as you can to verify effectiveness of the software risk controls.

What is the best way to analyze data risks?

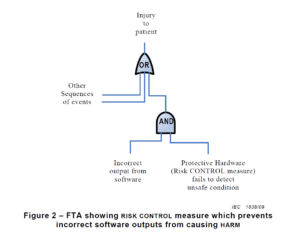

There are multiple risk analysis tools available to device and IVD manufacturers (e.g., preliminary hazard analysis, failure modes and effects analysis, and fault-tree analysis). Using a design failure modes and effects analysis (i.e., dFMEA) is the most common risk analysis tool, but a dFMEA is not the best tool for software risk analysis. There are two reasons for this. First, the dFMEA is a bottom-up approach that assumes you know all of the software functions that are needed–but you won’t. Second, the dFMEA will have multiple rows of effects for each failure mode because each cause of software failure can overlap with multiple software functions. Therefore, the best way to analyze data risks is a fault-tree analysis (i.e., FTA). The FTA is the best tool for analysis of software data hazards because you only need three fault trees: 1) Mix-up of data, 2) Loss of data, and 3) Modification of data. In each of these FTAs, all of the potential causes of software failure will be identified in the branches of the fault tree. Analyzing the fault tree structure, specifically the position of OR gates, can assist in software design. OR logic gates that can result in critical failures need additional software risk controls to prevent a single cause of software failure from creating a serious hazardous situation.

How to build a fault tree

The first step of your software risk analysis should be to identify data hazards. Once you identify the data hazards, you can build a fault tree for each of the three possible software failures: mix-up of data, 2) incomplete data, and 3) modification of data. Each data hazards can cause multiple software failure modes, but the type of logic gate will determine the outcome of that data hazard. An OR gate will result in software failures if there is just one hazardous event, while an AND gate requires at least two hazardous events to occur before the software failure will occur. The position of the OR/AND gate also impacts the potential for software failures.

Data Hazards for SaMD and SiMD Read More »