De Novo pre IDE Meeting

The article describes the most critical part of the preparation for a De Novo Classification Request, the De Novo pre IDE meeting.

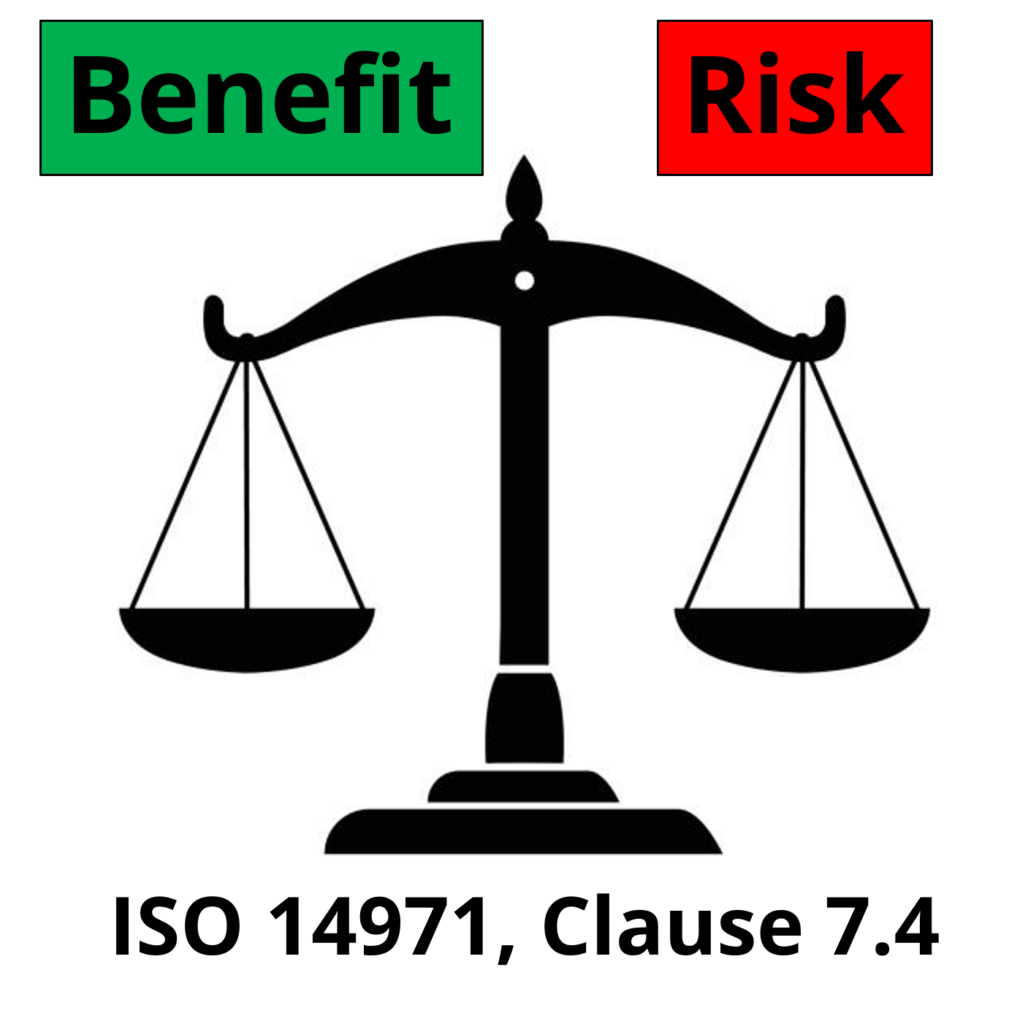

There are two critical differences between a De Novo classification request and a 510k submission. First, 510k clearance is based upon a substantial equivalence comparison of a device and a predicate device that is already marketed in the USA, while a De Novo classification is based upon a benefit-risk analysis of a device’s clinical benefits compared with the risk of harm to users and patients. Second, 510k clearance usually does not require clinical data to demonstrate safety and efficacy, while a De Novo classification request usually does require clinical data to demonstrate safety and efficacy. Therefore, it makes sense that the two most common challenges for innovative medical device companies are: 1) learning how to write a benefit-risk analysis, and 2) clinical study design. Success with both of these tasks can be significantly improved by requesting a De Novo pre IDE meeting with the FDA.

Benefit-risk analysis questions to ask during a De Novo pre IDE meeting

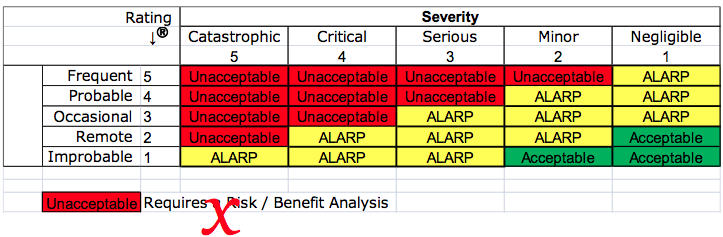

Most device companies are only familiar with substantial equivalence comparisons–not a benefit-risk analysis. The statement “the benefits outweigh the risks” is not a benefit-risk analysis. Medical device regulations have been changing toward an emphasis on benefit-risk anlysis. For example, the European MDD mentions benefit-risk analysis eight times, while Regulation (EU) 2017/745 mentions benefit-risk analysis 69 times. Despite the obvious increased emphasis on benefit-risk analysis in the new EU Regulations, ISO 14971:2019 only requires a benefit-risk analysis for unacceptable risks. The international standard also does not clearly explain how to perform a benefit-risk analysis. The best explanation for how to perform a benefit-risk analysis was provided in the FDA guidance, but now the ISO/TR 24971:2020 guidance includes detailed guidance in Clause 7.4.

In addition to reading ISO/TR 24971 and the FDA guidance, you will need to systematically identify all of the current alternative methods of treatment, diagnosis, or monitoring for your intended use. Therefore, you should ask in a pre-submission meeting if there are any additional devices or treatments that the FDA feels should be considered. You should review each of the alternative treatments for clinical studies that may help you in the design of your clinical study. You should carefully review the available clinical data for alternative treatments to help you quantify the risks and benefits associated with those treatments too. Finally, you should consider whether one or more of these alternative treatments might be a suitable control for your clinical study. Ideally, your clinical study design will show that the benefits of your device are greater, and the risks are less, but either may be enough for approval of your classification request. If you think the risks of your device are significantly less than alternative treatments, then ask the FDA about using this factor as an endpoint in your study design.

Clinical Study Design Considerations

Ideally, there is already a well-accepted clinical model for assessing efficacy for your desired indications. This means multiple, published, peer-reviewed journal articles. You might have a better method for evaluating subjects, but don’t propose that method instead of a “gold standard.” If you feel strongly that your method is more appropriate, propose both methods of evaluation. You also need multiple evaluators who can be objective. Randomization, blinding, and monitoring of clinical studies is critical to ensure an unbiased evaluation of clinical results. In general, it is difficult to design an unbiased post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) study. A common deficiency identified by the FDA is that post-market study performed outside the United States (OUS) has selection bias and covariate imbalance.

You also need to design your study with realistic expectations. Murphy’s law is always active. That means, “things will go wrong in any given situation if you give them a chance.” Therefore, you must avoid optimism and devise methods for detecting errors quickly. This is why electronic data capture systems and eSource is preferred for data collection instead of the manual collection of data on paper case study forms. Not only does it reduce errors in data collection, but it also facilitates remote monitoring of clinical sites. This includes asking questions that are open-ended or quantitative–instead of Yes/No questions or qualitative evaluations that encourage subjectivity. You can always anticipate every mistake that will be made, and open-ended questions often capture essential data that would otherwise be lost. Asking the quantitative questions also will provide you with additional data you can analyze, which may reveal unexpected relationships or help you to explain unexpected results. To help facilitate the development of these questions, try asking yourself how you could detect an error for each data point you are collecting. Then add a detection mechanism to your data collection plan wherever and whenever you can.

Goals of De Novo pre IDE Meeting

A pre-IDE meeting is not typically your first pre-submission meeting with the FDA. Usually, your first pre-submission meeting is to verify that the FDA agrees that the regulatory pathway is a De Novo classification request rather than a 510k submission. Hopefully, you also were able to review your overall testing plan with the FDA during your first pre-submission meeting. You may have even reviewed a clinical synopsis with the FDA during your initial pre-submission meeting. During the pre-IDE meeting, your goal is to finalize your clinical study protocol. That doesn’t mean that the FDA should agree 100% with your draft protocol. You want positive and negative feedback on all aspects of your protocol before the IDE submission. During the IDE review, changes will be made.

The most important aspects of getting right before the IDE submission are the fundamentals. Most of our De Novo clients feel that a control group is not possible, because they think that test subjects will know when a sham device is used. However, trying to avoid a control group is nearly impossible. The most important factors for why a control group is needed are:

- you need to minimize differences between experimental and control subjects, but you can’t do that if you are relying on data from other clinical studies

- you also need to ensure that your evaluation methods are identical, which is nearly impossible when performed by different people, at different facilities, using slightly different protocols

Another area of weakness in most draft clinical protocols is the method of evaluation. Specifically:

- Who is doing evaluations?

- Which endpoints are important?

- When are your endpoints?

- What are your acceptance criteria?

The last area to consider in a pre-IDE meeting is your statistical plan. You need a statistical plan, but the statistical analysis seldom appears to be the reason for the rejection of clinical data. The reason is that changes can be made to your statistical analysis of data after the study is completed, but you can’t change the data once the study is over. The FDA is now accepting adaptive designs that allow the company to analyze data during the study to recalculate the ultimate sample size needed based upon actual data rather than initial assumptions.

What are the basic milestones in an FDA pre IDE meeting?

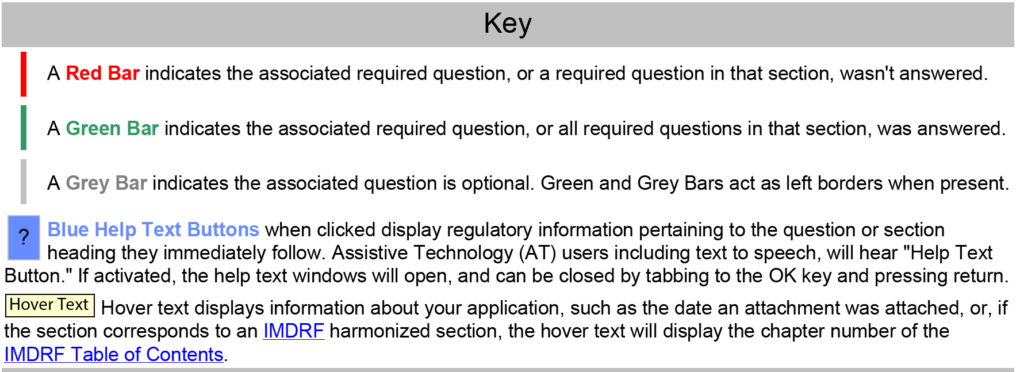

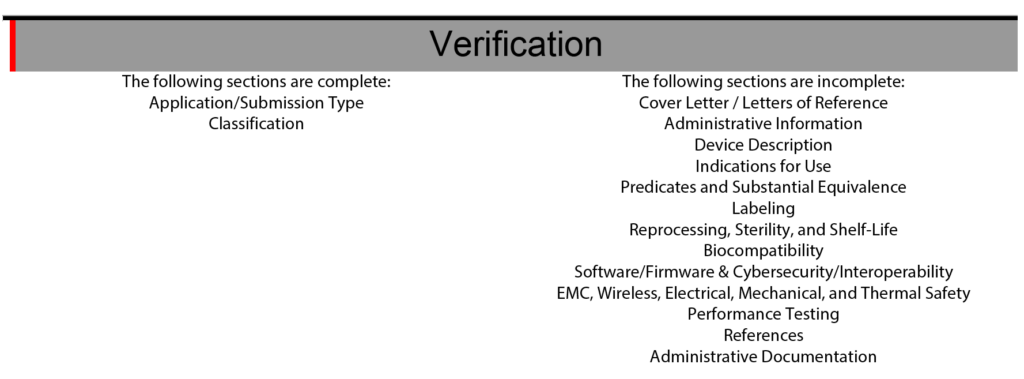

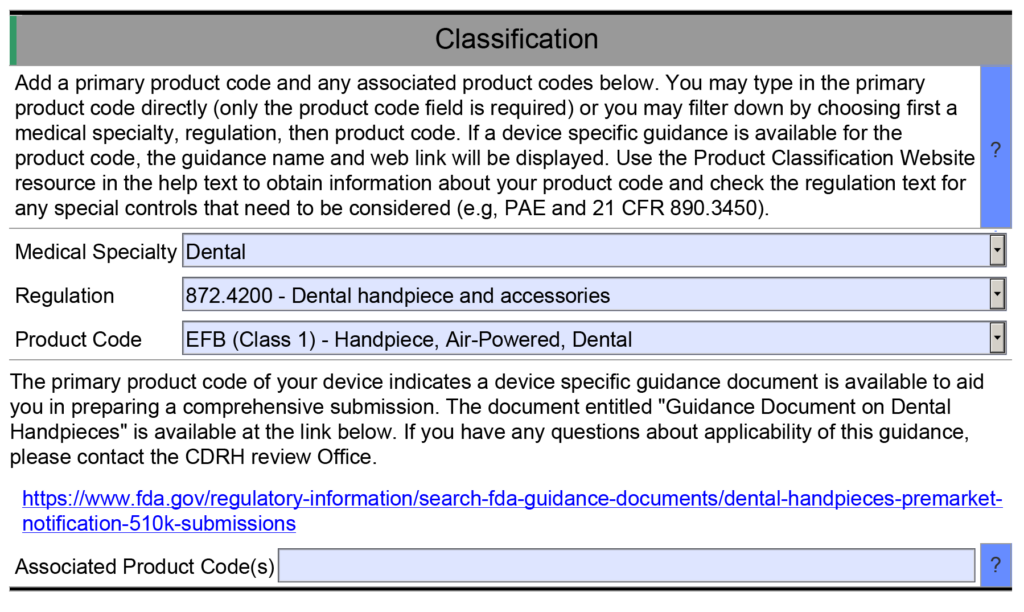

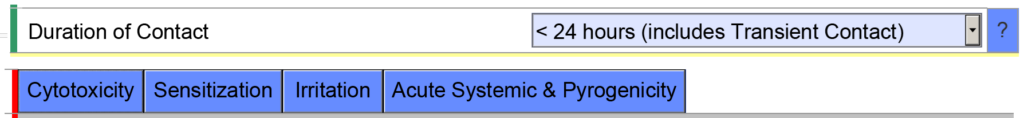

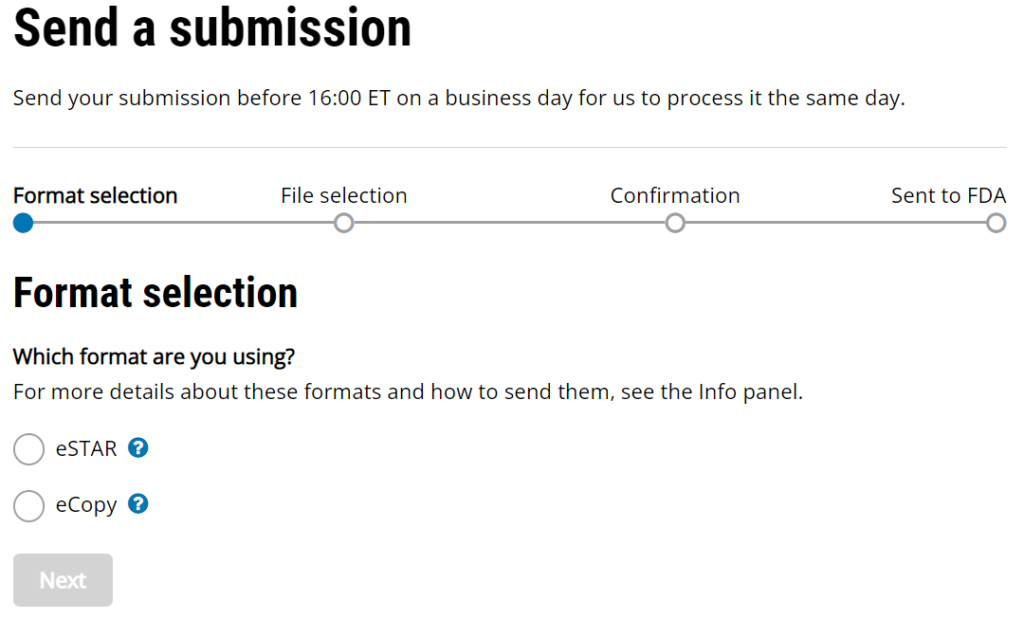

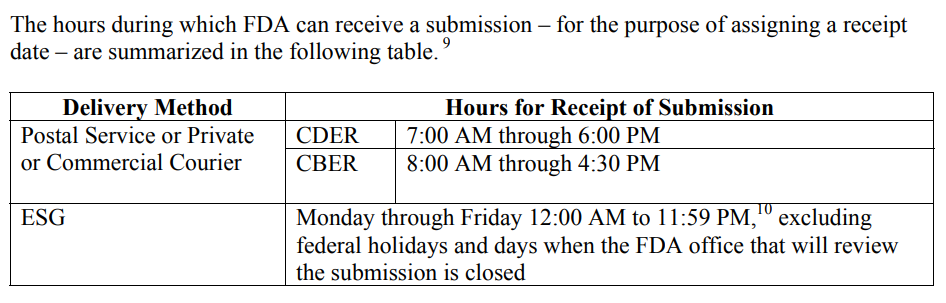

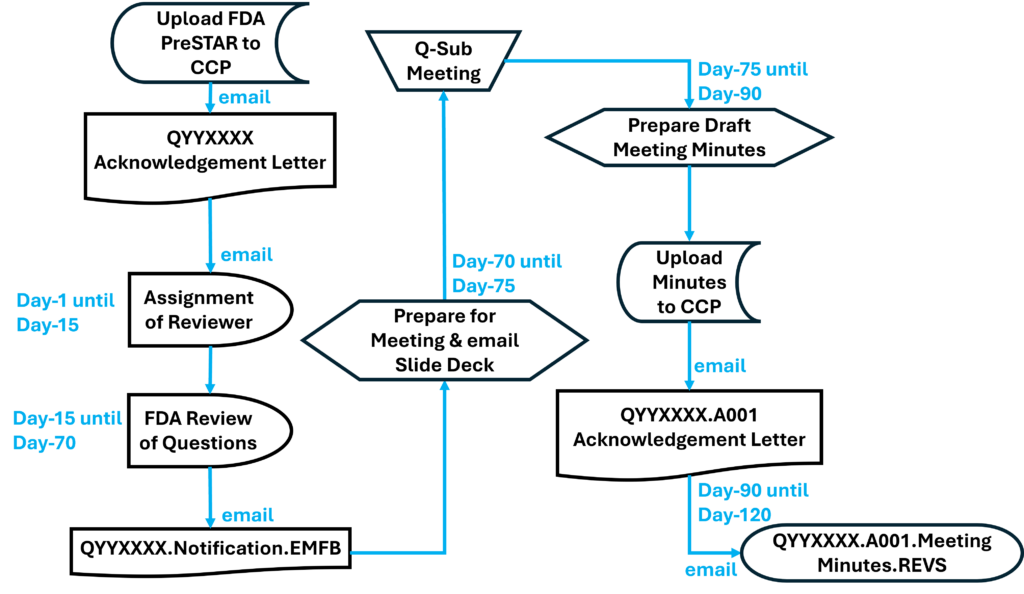

Once you have prepared your De Novo pre IDE meeting request and the FDA PreSTAR template indicates that the submission is complete, then you are ready to submit the PreSTAR to the FDA. There are 11 steps in the process for an FDA pre-submission meeting request (see flow chart above). The following is a brief summary of each milestone the process:

- Upload your completed FDA PreSTAR to the FDA Customer Collaboration Portal (CCP)

- Within seconds of uploading your file, you will receive an automated email acknowledging the uploading of the file to the CCP, but your real acknowledgement is a letter your receive by email the following day that has the Q-Sub number assigned to your request (i.e., QYYXXXX).

- A preliminary review of the PreSTAR used to be performed and a checklist was filled out, but with the use of the PreSTAR template the FDA is now only conducting a technical review. Once the technical review is completed, a lead reviewer is assigned and you will receive an email notifying you of who your reviewer is. This process usually is completed in 15 days.

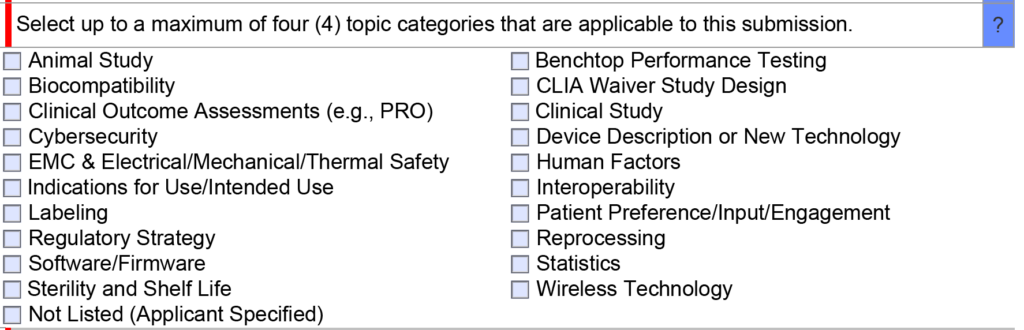

- Once the FDA lead reviewer is assigned, the lead reviewer will ask subject matter experts to review and respond to each of the questions in the De Novo pre IDE meeting request. Pre-submissions are limited to a maximum of four topics, and therefore, there should only be a need for a four subject matter experts. The lead reviewer may be one of the subject matter experts. Typically the assistant director of the review panel (i.e., medical specialty) will also participate, and sometimes the director will also participate. This review process will occur from day 15 until day 70 of the pre-submission process. The lead reviewer will also contact you by email to coordinate a date and time for scheduling the pre-submission teleconference.

- Approximately five days before the scheduled De Novo pre IDE meeting teleconference, the FDA lead reviewer will provide a email response to your questions. The file name of the document sent by the lead reviewer will be in the following format: “QYYXXXX.Notification.EMFB.”

- Your team will need to review the FDA responses to each question and decide whether you want to ask any clarification questions. If you don’t have any clarification questions, you can cancel the FDA teleconference. A slide deck is not required for the teleconference, but if you decide to create a slide deck the FDA would like to receive it by email ~48 hours before the teleconference.

- For the De Novo pre IDE meeting teleconference, the FDA lead reviewer provides login information for a Microsoft Teams or Zoom teleconference in advance of the meeting. Attendees can login approximately 5 minutes before the start. The meeting begins with introductions, and then the company will present their slides and ask clarification questions. At the end of each slide, it is a good practice to ask if anyone from the company has additional questions, and then you should ask if the FDA have anything they would like to ask. We recommend alternating speakers for presentation of slides. This gives multiple people practice presenting to the FDA, it provides some variety of speakers, it increases engagement during meetings, and it allows people that are not speaking time to catch-up on their notes. The FDA will not permit recordings during the meeting. At the end of the meeting, you will want to leave approximately 5 minutes for summarizing any action items for your company or the FDA.

- After the teleconference most companies will conduct a debrief meeting without the FDA. Notes from each person will be shared with the person designated for creating draft meeting minutes. The minutes are intended to be only a summary of what was discussed–not a transcription. You have 15 calendar days to create the draft.

- Once the company agrees on a final draft of the meeting minutes you will prepare an FDA eCopy and upload it to the FDA CCP. If you created a slide deck, the slide deck should be included with the meeting minutes as a second document in the FDA eCopy. Lead reviewers will also sometimes request an MS Word version of the minutes be emailed directly to them to facilitate editing the minutes.

- Within seconds of uploading your FDA eCopy of the minutes, you will receive an automated email acknowledging the uploading of the FDA eCopy to the CCP. The document number assigned for meeting minutes is in the following format: QYYXXXX.A001.

- The FDA will take 30 days to review your draft meeting minutes. The minutes will be redlined by the FDA with what the FDA intended to say regarding your questions so it may differ from exactly what was said. You will receive an email with a letter attached. The filename of the letter will be: QYYXXXX.A001.Meeting Minutes.REVS. You can dispute the minutes if you disagree with the FDA’s redlines.

How to you use meeting minutes in your final De Novo application?

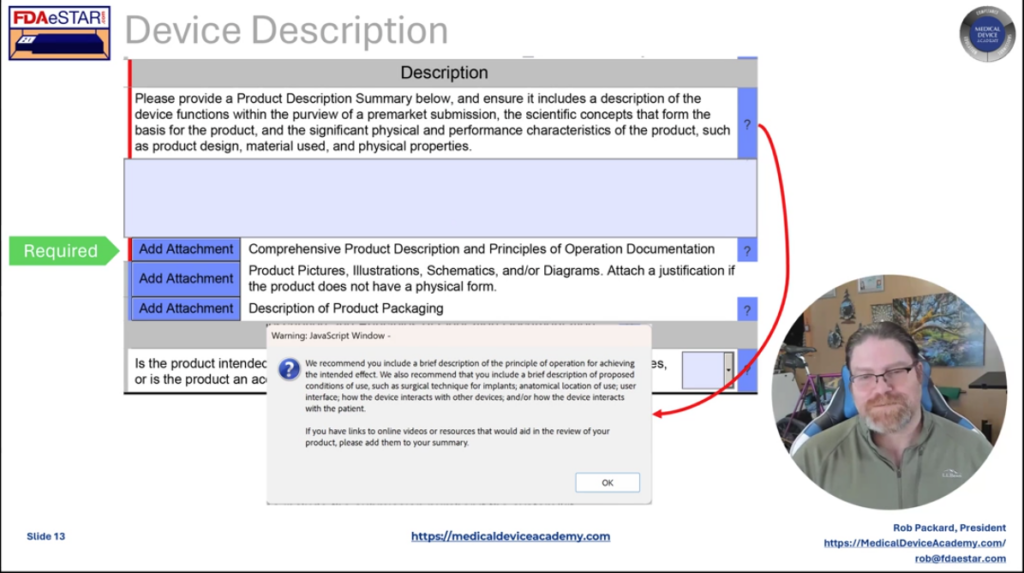

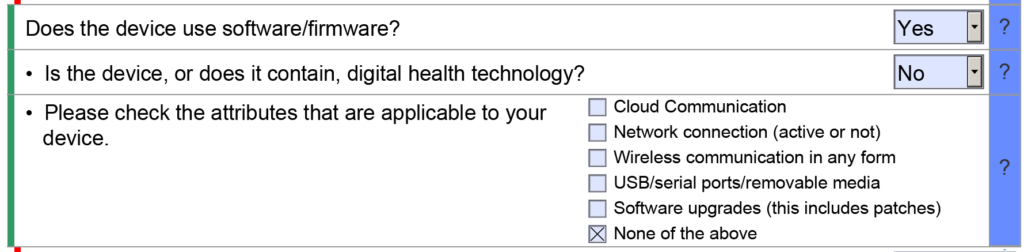

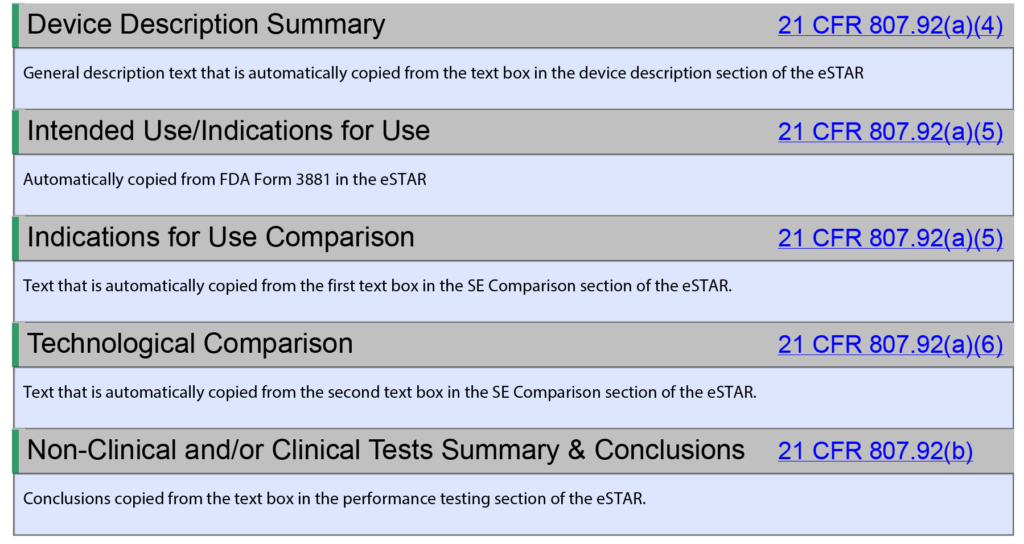

In your FDA eSTAR, you will need to attach a copy of the meeting minutes from any pre-submissions you had with the FDA. You will also need to provide a response memo indicating how you addressed any concerns or questions the FDA raised during those pre-submissions. Both documents will be attached to the eSTAR. We recommend using a tabular format and alternating between blue and black font to clearly separate the minutes from your responses.

Do you need more information about De Novo applications?

We created a cornerstone webpage that summarizes our content about De Novo applications. All of our webinars about De Novo applications and our De Novo templates can be purchased as part of our 510k Course Series. You can also learn a lot about clinical study design by purchasing Medical Device Academy’s Clinical Procedure (SYS-009). Finally, try searching the De Novo Reclassification Summaries for examples of how other companies designed their clinical studies to demonstrate safety and efficacy for a De Novo application.

De Novo pre IDE Meeting Read More »