Design Controls Implementation

Design controls can be overwhelming, but you can learn the process using this step-by-step guide to implementing design controls.

Design Controls Implementation

Design Controls Implementation

You can implement design controls at any point during the development process, but the earlier you implement your design process the more useful design controls will be. The first step of implementing design controls is to create and design controls procedure. You will also need at least two of the following additional quality system procedures:

- Risk Management Procedure (SYS-010)

- Software Development and Validation (SYS-044)

- Usability Procedure (SYS-048)

- Cybersecurity Work Instruction (WI-007)

A risk management file (in accordance with ISO 14971:2019) is required for all medical devices, and usability engineering or human factors engineering (in accordance with IEC 62366-1) is required for all medical devices. The software and cybersecurity procedures listed above are only required for products with 1) software and/or firmware, and 2) wireless functionality or an access point for removable media (e.g., USB flash drive or SD card).

Step 2: Design controls training

Even though the requirement for design controls has been in place for more than 25 years, there are still far too many design teams that struggle with understanding these requirements. Medical device regulations are complex, but design controls are the most complex process in any quality system. The reason for this is that each of the seven sub-clauses represents a mini-process that is equivalent in complexity to CAPA root cause analysis. Many companies choose to create separate work instructions for each sub-clause.

Medical Device Academy’s training philosophy is to distill processes down to discrete steps that can be absorbed and implemented quickly. We use independent forms to support each step and develop training courses with practical examples, instead of writing a detailed procedure(s). The approach we teach removes complexity from your design control procedure (SYS-008). Instead, we rely upon the structure of step-by-step forms completed at each stage of the design process.

If you are interested in design control training, Rob Packard will be hosting the 3rd edition of our Design Controls Training Webinar on Friday, August 11, 2023, @ 9:30 am EDT.

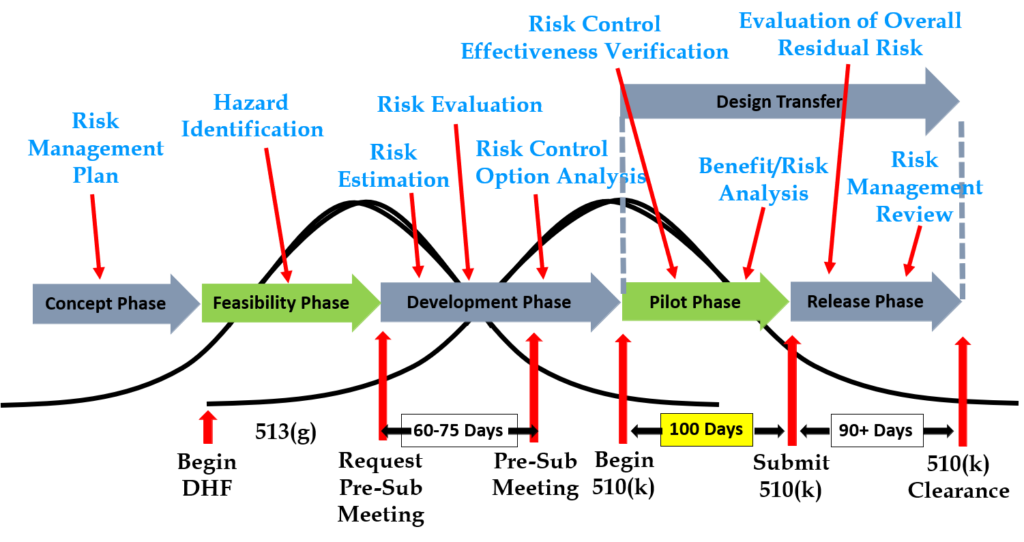

Step 3: Gathering post-market surveillance data

Post-market surveillance is not currently required by the FDA in 21 CFR 820, but it is required by ISO 13485:2016 in Clause 7.3.3c) (i.e., “[Design and development inputs] shall include…applicable outputs(s) of risk management”). The FDA is expected to release the plans for the transition to ISO 13485 in FY 2024, but most companies mistakenly think that the FDA does not require consideration of post-market surveillance when they are designing new devices. This is not correct. There are three ways the FDA expects post-market surveillance to be considered when you are developing a new device:

- Complaints and adverse events associated with previous versions of the device and competitor devices should be identified as input to the risk management process for hazard identification.

- If the device incorporates software, existing vulnerabilities of the off-the-shelf software (including operating systems) should be identified as part of the cybersecurity risk assessment process.

- During the human factors process, you should search for known use errors associated with previous versions of the device and competitor devices; known use-related risks should also include any potential use errors identified during formative testing.

Even though the FDA does not currently require compliance with ISO 13485, the FDA does recognize ISO 14971:2019, and post-market surveillance is identified as an input to the risk management process in Clause 4.2 (see note 2), Clause 10.4, and Annex A.2.10.

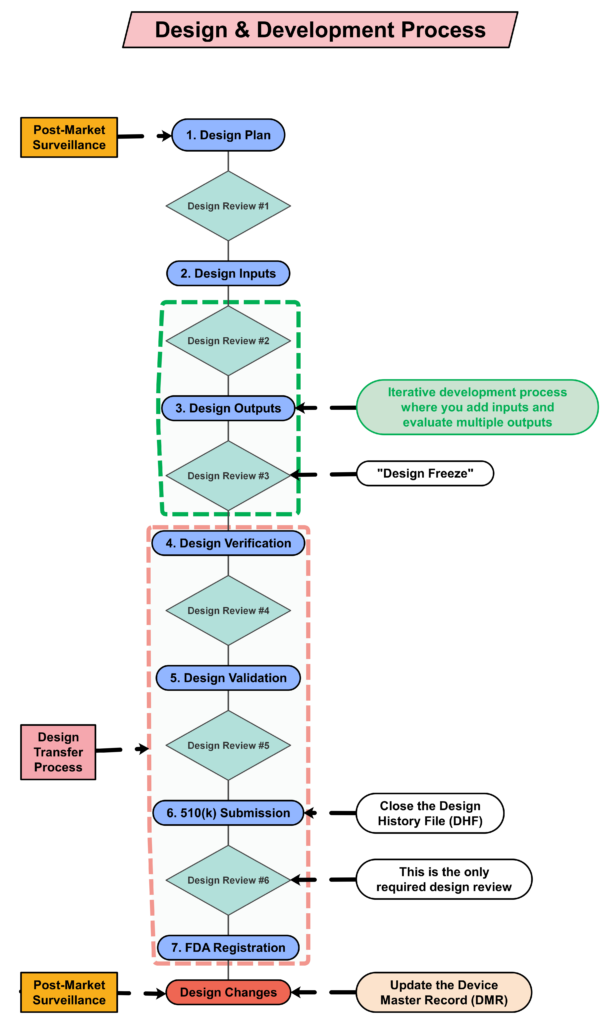

Step 4: Creating a design plan

You are required to update your design plan as the development project progresses. Most design and development projects take a year before the company is ready to submit a 510k submission to the FDA. Therefore, don’t worry about making your first version of the plan perfect. You have a year to make lots of improvements to your design plan. At a minimum, you should be updating your design plan during each design review. One thing that is important to capture in your first version, however, is the correct regulatory pathway for your intended markets. If you aren’t sure which markets you plan to launch in, you can select one market and add more later, or you can select a few and delete one or more later. Your design plan should identify the resources needed for the development project, and you should estimate when you expect to conduct each of your design reviews.

Contents of your design plan

The requirement for design plans is stated in both Clause 7.3.1 of the ISO Standards, and Section 21 CFR 820.30b of the FDA QSR. You can make your plan as detailed as you need to, but I recommend starting simple and adding detail. Your first version of a design plan should include the following tasks:

- Identification of the regulatory pathway based on the device risk classification and applicable harmonized standards.

- Development of a risk management plan

- Approval of your design plan (1st design review)

- Initial hazard identification

- Documentation and approval of user needs and design inputs (2nd design review)

- Risk control option analysis

- Reiterative development of the product design

- Risk analysis

- Documentation and approval of design outputs implementation of risk control measures (3rd design review)

- Design verification and verification of the effectiveness of risk control measures (4th design review)

- Design validation and verification of the effectiveness of risk control measures that could not be verified with verification testing alone

- Clinical evaluation and benefit/risk analysis (5th design review)

- Development of a post-market surveillance plan with a post-market risk management plan

- Development of a draft Device Master Record/Technical File (DMR/TF) Index

- Regulatory approval (e.g., 510k clearance) and closure of the Design History File (DHF)

- Commercial release (6th and final design review)

- Review lessons learned and initiate actions to improve the design process

Step 5: Create a detailed testing plan

Your testing plan must indicate which recognized standards you plan to conform with, and any requirements that are not applicable should be identified and documented with a justification for the non-applicability. The initial version of your testing plan will be an early version of your user needs and design inputs. However, you should expect the design inputs to change several times. After you receive feedback from regulators is one time you may need to make changes to design inputs. You may also need to make changes when you fail your testing (i.e., preliminary testing, verification testing, or validation testing). If your company is following “The Lean Startup” methodology, your initial version of the design inputs will be for a minimum viable product (i.e., MVP). As you progress through your iterative development process, you will add and delete design inputs based on customer feedback and preliminary testing. Your goal should be to fail early and fail fast because you don’t want to get to your verification testing and fail. That’s why we conduct a “design freeze,” prior to starting the design verification testing and design transfer activities.

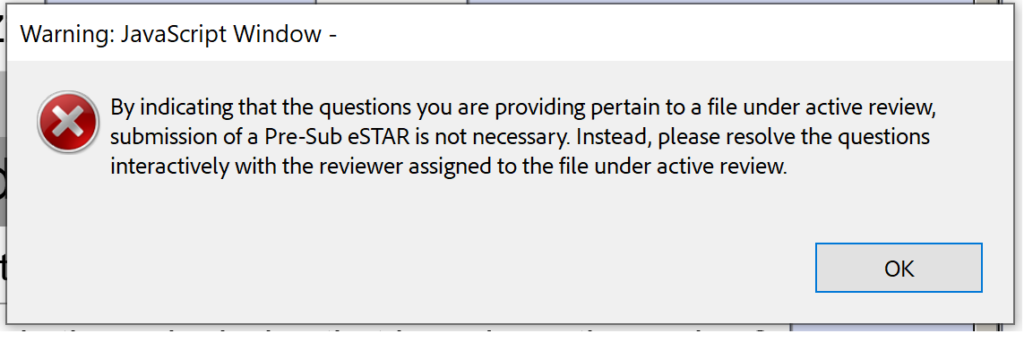

Step 6: Request a pre-submission meeting with the FDA

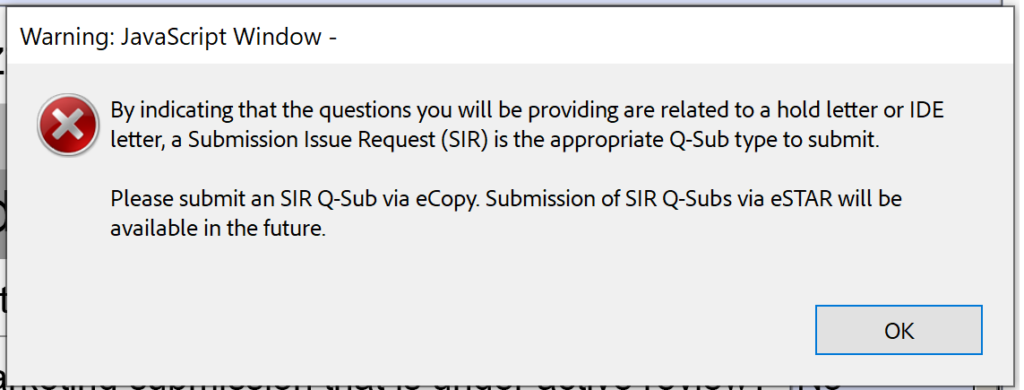

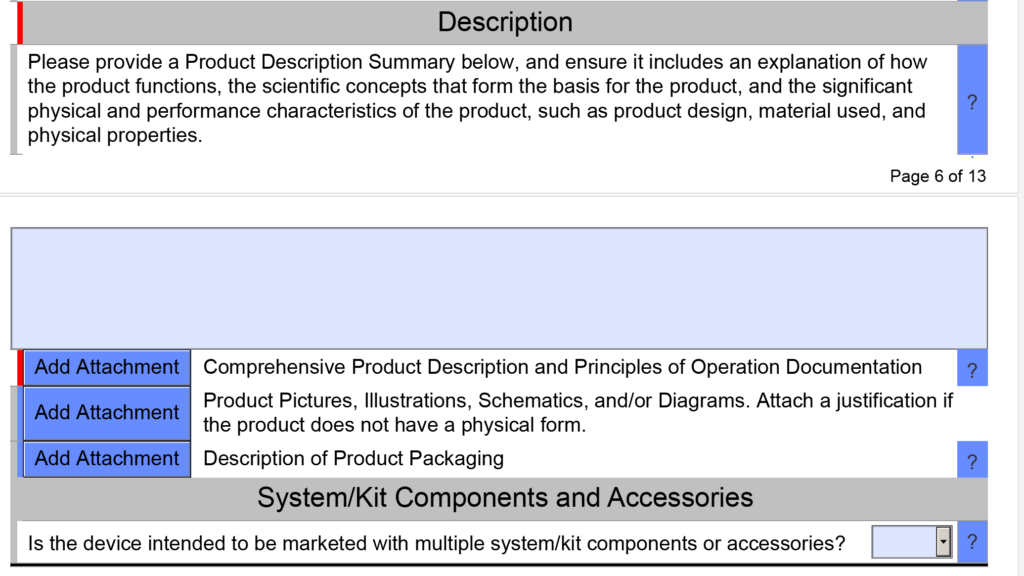

Design inputs need to be requirements verified through the use of a verification protocol. If you identify external standards for each design input, you will have an easier time completing the verification activities, because verification tests will be easier to identify. Some standards do not include testing requirements, and there are requirements that do not correspond to an external standard. For example, IEC 62366-1 is an international standard for usability engineering, but the standard does not include specific testing requirements. Therefore, manufacturers have to develop their own test protocol for validation of the usability engineering controls implemented. If your company is developing a novel sterilization process (e.g., UV sterilization), you will also need to develop your own verification testing protocols. In these cases, you should submit the draft protocols to the FDA (along with associated risk analysis documentation) to obtain feedback and agreement with your testing plan. The method for obtaining written feedback and agreement with a proposed testing plan is to submit a pre-submission meeting request to the FDA (i.e., PreSTAR).

Step 7: Iterative development is how design controls really work

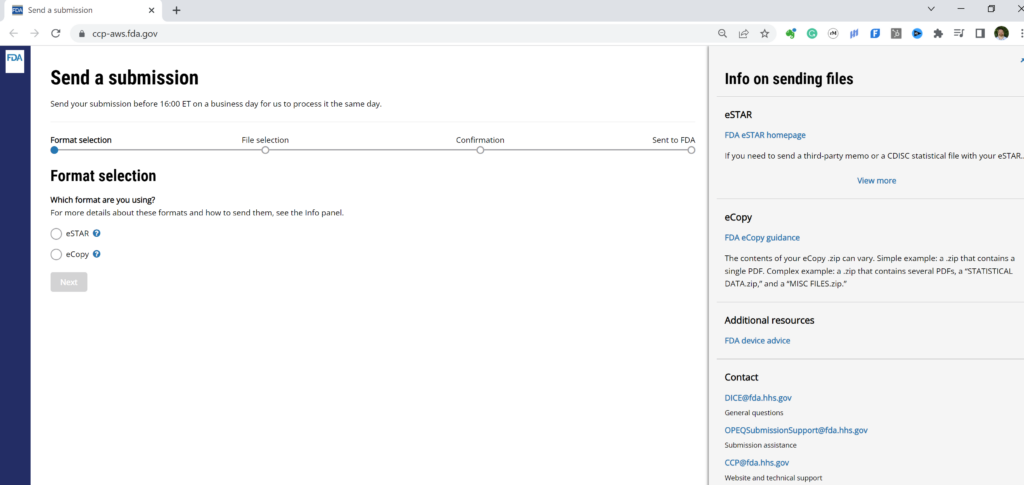

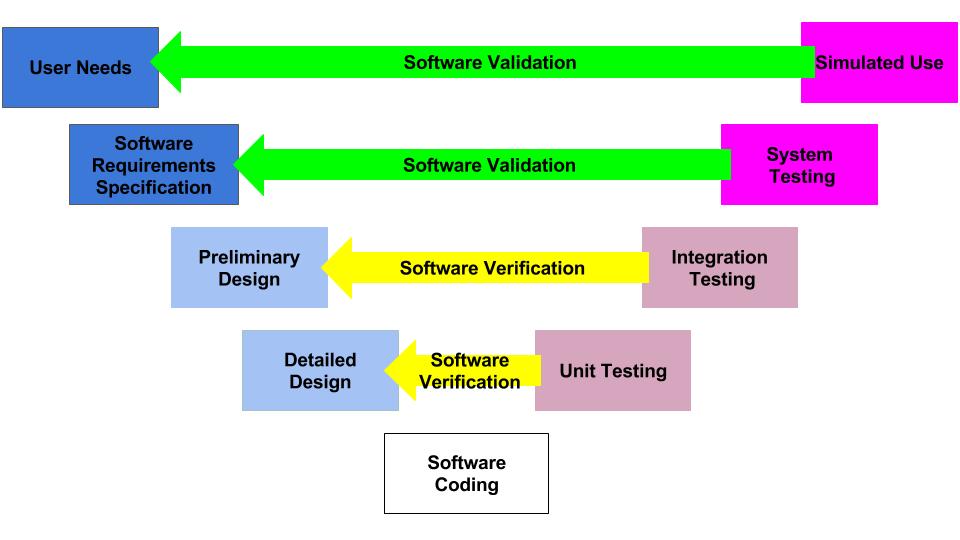

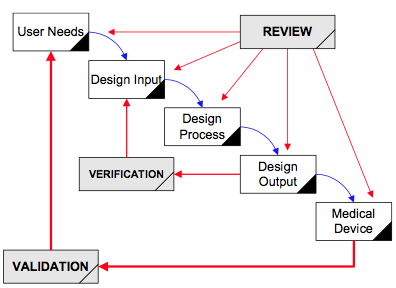

Design controls became a legal requirement in the USA in 1996 when the FDA updated the quality system regulations. At that time, the “V-diagram” was quite new and limited to software development. Therefore, the FDA requested permission from Health Canada to reprint the “Waterfall Diagram” in the design control guidance that the FDA released. Both diagrams are models. They do not represent best practices, and they do not claim to represent how the design process is done in most companies. The primary information that is being communicated by the “Waterfall Diagram” is that user needs are validated while design inputs are verified. The diagram is not intended to communicate that the design process is linear or must proceed from user needs, to design inputs, and then to design outputs. The “V-Diagram” is meant to communicate that there are multiple levels of verification and validation testing that occur, and the development process is iterative as software bugs are identified. Both models help teach design and development concepts, but neither is meant to imply legal requirements. One of the best lessons to teach design and development teams is that this is a need to develop simple tests to screen design concepts so that design concepts can fail early and fail fast–before the design is frozen. This process is called “risk control option analysis,” and it is required in clause 7.1 of ISO 14971:2019.

Step 8: “Design Freeze”

Design outputs are drawings and specifications. Ensure you keep them updated and control the changes. When you finally approve the design, this is approval of your design outputs (i.e., selection of risk control options). The final selection of design outputs or risk control measures is often conducted as a formal design review meeting. The reason for this is that the cost of design verification is significant. There is no regulatory or legal requirement for a “design freeze.” In fact, there are many examples where changes are anticipated but the team decides to proceed with the verification testing anyway. The best practice developed by the medical device industry is to conduct a “design freeze.” The design outputs are “frozen” and no further changes are permitted. The act of freezing the design is simply intended to reduce the business risk of spending money on verification testing twice because the design outputs were changed during the testing process. If a device fails testing, it will be necessary to change the design and repeat the testing, but if every person on the design team agrees that the need for changes is remote and the company should begin testing it is less likely that changes will be made after the testing begins.

Step 9: Begin the design transfer process

Design transfer is not a single event in time. Transfer begins with the release of your first drawing or specification to purchasing and ends with the commercial release of the product. The most common example of a design transfer activity is the approval of prototype drawings as a final released drawing. This is common for molded parts. Several iterations of the plastic part might be evaluated using 3D printed parts and machined parts, but in order to consistently make the component for the target cost an injection mold is typically needed. The cost of the mold may be $40-100K, but it is difficult to change the design once the mold is built. The lead time for injection molds is often 10-14 weeks. Therefore, a design team may begin the design transfer process for molded parts prior to conducting a design freeze. Another component that may be released earlier as a final design is a printed circuit board (PCB). Electronic components such as resistors, capacitors, and integrated circuits (ICs) may be available off-the-shelf, but the raw PCB has a longer lead time and is customized for your device.

Step 10: Verification of Design Controls

Design verification testing requires pre-approved protocols and pre-defined acceptance criteria. Whenever possible, design verification protocols should be standardized instead of being project-specific. Information regarding traceability to the calibrated equipment identification and test methods should be included as a variable that is entered manually into a blank space when the protocol is executed. The philosophy behind this approach is to create a protocol once and repeat it forever. This results in a verification process that is consistent and predictable, but it also eliminates the need for review and approval of the protocol for each new project. Standardized protocols do not need to specify a vendor or dates for the testing, but you might consider documenting the vendor(s) and duration of the testing in your design inputs to help with project management and planning. You might also want to use a standardized template for the format and content of your protocol and report. The FDA provides a guidance document specifically for the report format and content for non-clinical performance testing.

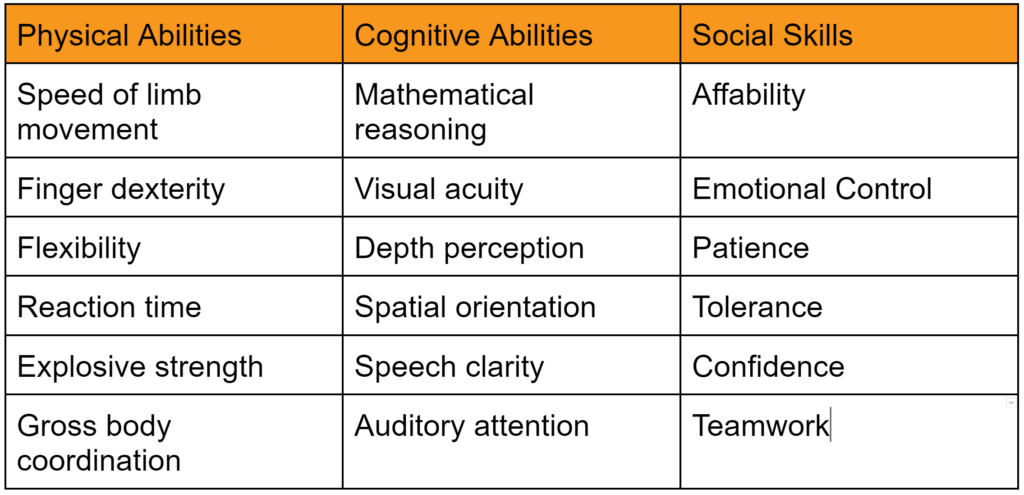

Step 11: Validation of Design Controls

Design validation is required to demonstrate that the device meets the user’s and patient’s needs. User needs are typically the indications for use–including safety and performance requirements. Design validation should be more than bench testing. Ensure that animal models, simulated anatomical models, finite element analysis, and human clinical studies are considered. One purpose of design validation is to demonstrate performance for the indications for use, but validating that risk controls implemented are effective at preventing use-related risks is also important. Therefore, human factors summative validation testing is one type of design validation. Human factors testing will typically involve simulated use with the final version of the device and intended users. Validation testing usually requires side-by-side non-clinical performance testing with a predicate device for a 510k submission, while CE Marking submissions typically require human clinical data to demonstrate safety and performance.

Step 12: FDA 510k Submission

FDA pre-market notification, or 510k submission, is the most common type of regulatory approval required for medical devices in the USA. FDA submissions are usually possible to submit earlier than other countries, because the FDA does not require quality system certification or summary technical documents, and performance testing data is usually non-clinical benchtop testing. FDA 510k submissions also do not require submission of process validation for manufacturing. Therefore, most verification and validation is conducted on “production equivalents” that were made in small volume before the commercial manufacturing process is validated. The quality system and manufacturing process validation may be completed during the FDA 510k review.

Step 13: The Final Design Review

Design reviews should have defined deliverables. We recommend designing a form for documenting the design review, which identifies the deliverables for each design review. The form should also define the minimum required attendees by function. Other design review attendees should be identified as optional—rather than required reviewers and approvers. If your design review process requires too many people, this will have a long-term impact upon review and approval of design changes.

The only required design review is a final design review to approve the commercial release of your product. Do not keep the DHF open after commercial release. All changes after that point should be under production controls, and changes should be documented in the (DMR)/Technical File (TF). If device modifications require a new 510k submission, then you should create a new design project and DHF for the device modification. The new DHF might have no changes to the user needs and design inputs, but you might have minor changes (e.g., a change in the sterilization method requires testing to revised design inputs).

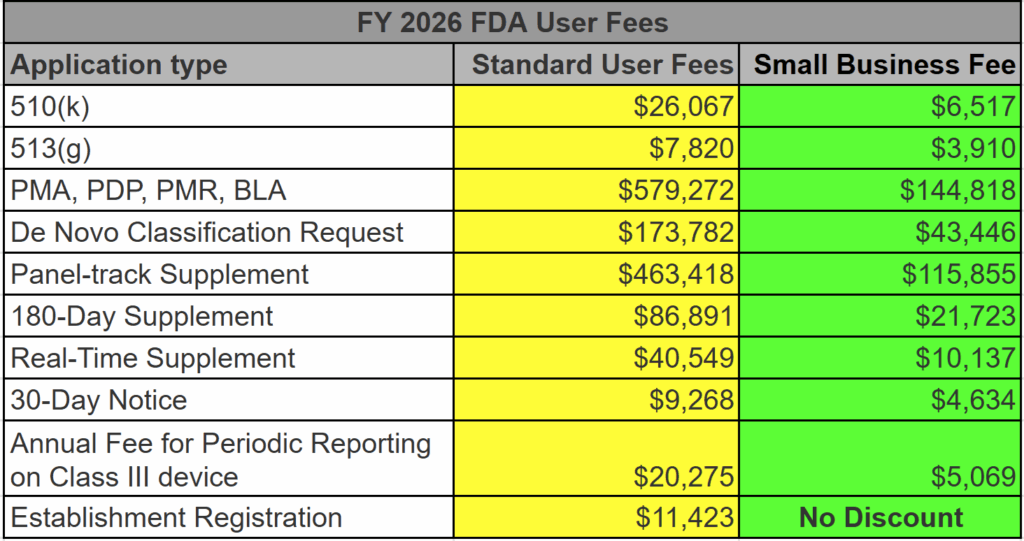

Step 14: FDA Registration

Within 30 days of initial product distribution in the USA, you are required to register your establishment with the FDA. Registration must be renewed annually between October 1 and December 31, and registration is required for each facility. If your company is located outside the USA, you will need an initial importer that is registered and you will need to register before you can ship the product to the USA. Non-US companies must also designate a US Agent that resides in the USA. At the time of FDA registration, your company is expected to be compliant with all regulations for the quality system, UDI, medical device reporting, and corrections/removals.

Step 15: Post-market surveillance is the design control input for the next design project

One of the required outputs of your final design review is your DMR Index. The DMR Index should perform a dual function of also meeting technical documentation requirements for other countries, such as Canada and Europe. A Technical File Index, however, includes additional documents that are not required in the USA. One of those documents is your post-market surveillance plan and the results of post-market surveillance. That post-market surveillance is an input to your design process for the next generation of products. Any use errors, software bugs, or suggestions for new functionality should be documented as post-market surveillance and considered as potential inputs to the design process for future design projects.

Step 16: Monitoring your design controls process

Audit your design controls process to identify opportunities for improvement and preventive actions. Audits should include a review of the design process metrics, and you may consider establishing quality objectives for the improvement of the design process. This last step, and the standardization of design verification protocols in step five (5), are discussed in further detail in another blog by Medical Device Academy.

Design Controls Implementation Read More »