Combining 510k with CE Marking Submissions

Learn how to create a regulatory plan for combining 510k with CE marking submissions in parallel instead of doubling your workload.

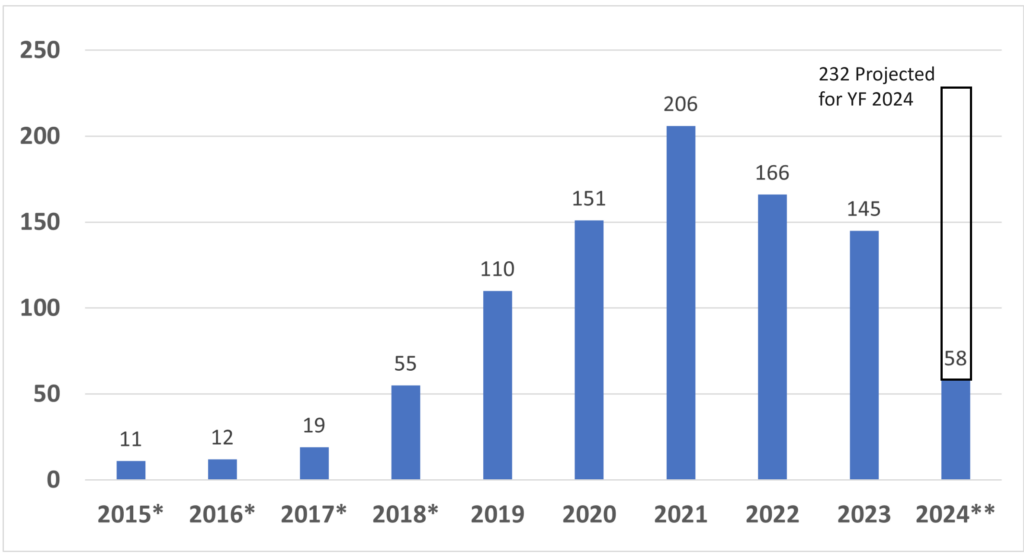

My first medical device regulatory submission was for CE Marking, while my second regulatory submission was for a 510k submission of the same product. Preparing submissions for different countries in parallel is a common path for medical device regulatory submissions, but it is also an inefficient path. If you know that you will be submitting both types of documents, then you should plan for this from the start and reduce your workload by at least 35%.

The reason why you can quickly reduce your workload by more than 65% is that both submission have very similar sections. Therefore, you can write the content for those sections in such a way that the material can be used for your 510k submission and CE Marking.

Identify duplicate sections in when combining 510k with CE marking projects

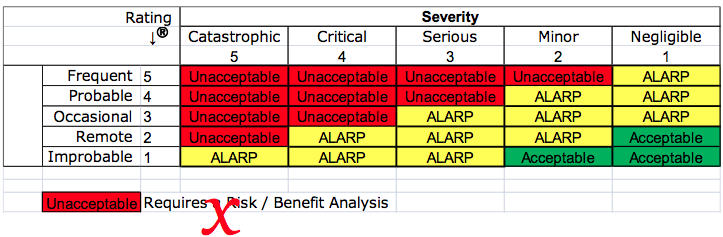

Most of your testing requirements should be identical when you are combining 510k with CE Marking submissions. However, the way the testing is presented is different. For your 510k submission you will attach the full testing report and write a brief statement about how the testing supports substantial equivalence. In contrast, CE marking technical files require a summary technical document or STED. The STED is a summary of each test that was performed. If you aren’t sure what testing is required, we created a test plan webinar to address this question specifically. Most of the work will be duplicated between your two test plans, but any outliers should be identified. For example, biocompatibility will need to include a biological evaluation plan (BEP) and biological evaluation report (BER), but this is optional for a 510k submission. There are also FDA requirements that are not required for CE marking, such as material mediated pyrogenicity testing and bacterial endotoxin testing for each production lot. In general, the possible testing categories are:

- biocompatibility

- sterilization

- shelf-life

- distribution

- reprocessing

- software

- cybersecurity

- wireless coexistence

- interoperability

- EMC

- electrical safety

- non-clinical performance

- human factors

- animal studies

- human clinical studies

There are a few other sections of your 510k and CE marking submissions that are nearly identical:

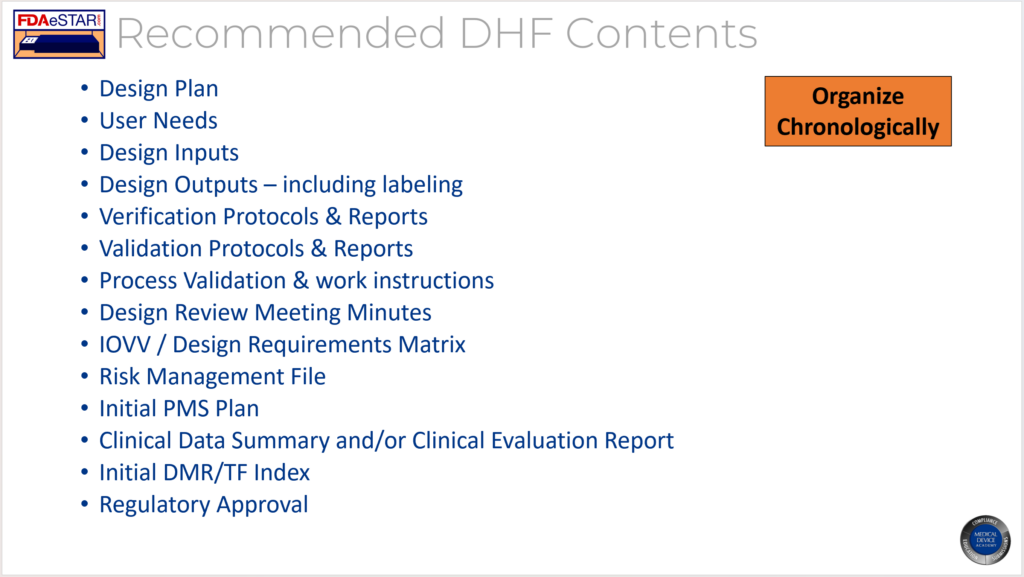

How to organize your medical device files when combining 510k with CE marking

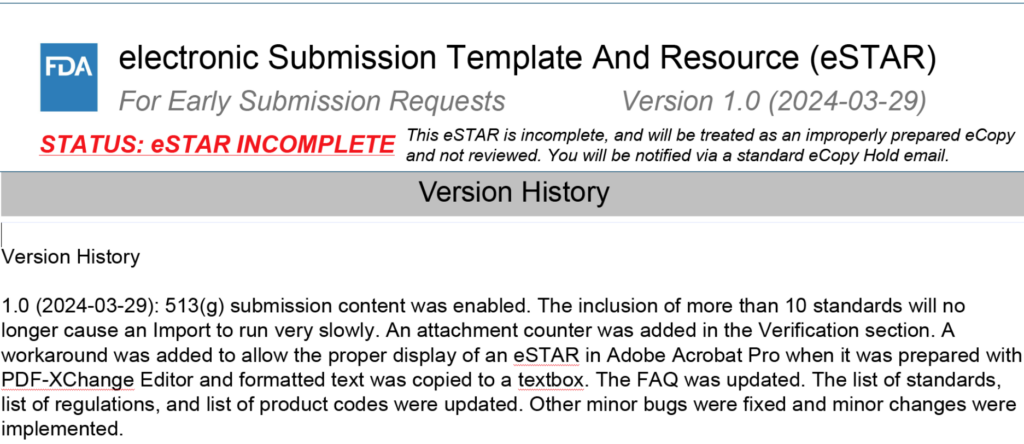

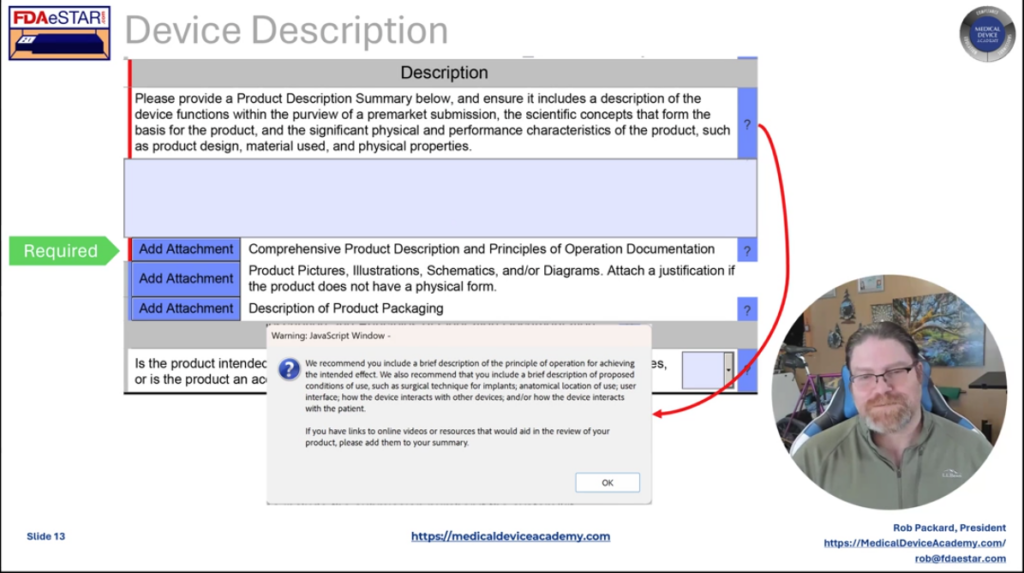

The new FDA eSTAR has a unique PDF template that must be used for organizing your submission but Patrick Axtell, the person that helped create the FDA eSTAR templates, is also the Coordinator for the IMDRF Regulated Product Submission Working Group. He has inserted links in the eSTAR sections that cross-reference to the Regulated Product Submission Table of Content (i.e., RPS ToC). Therefore, best practice is to organize your medical device file in accordance with the RPS ToC:

-

Non-In Vitro Diagnostic Device Regulatory Submission Table of Contents (nIVD ToC)

-

In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Device Regulatory Submission Table of Contents (IVD ToC)

Identify sections unique to an FDA eSTAR 510k

There are only a few sections of the FDA eSTAR 510k that are unique. The following is a list of those sections:

- Substantial Equivalence Comparison Table – only table is required with FDA eSTAR

- Truthful and Accuracy Statement – template is provided by the FDA

- 510(k) Summary – automatically generated by the FDA eSTAR

- User Fee Cover Sheet Form 3601 – generated by the FDA DFUF website when you pay the FDA user fee

- Declarations of Conformity – automatically generated by the FDA eSTAR (unless you are only partially compliant with a standard)

Technical Files for CE Marking also have a few unique sections, such as:

- GSPR Checklist

- Classification Rationale

- CE Marking Application to Notified Body

- Declaration of Conformity

- Table of Contents (i.e., TF Index)

Combining 510k with CE marking – how to construct your regulatory plan

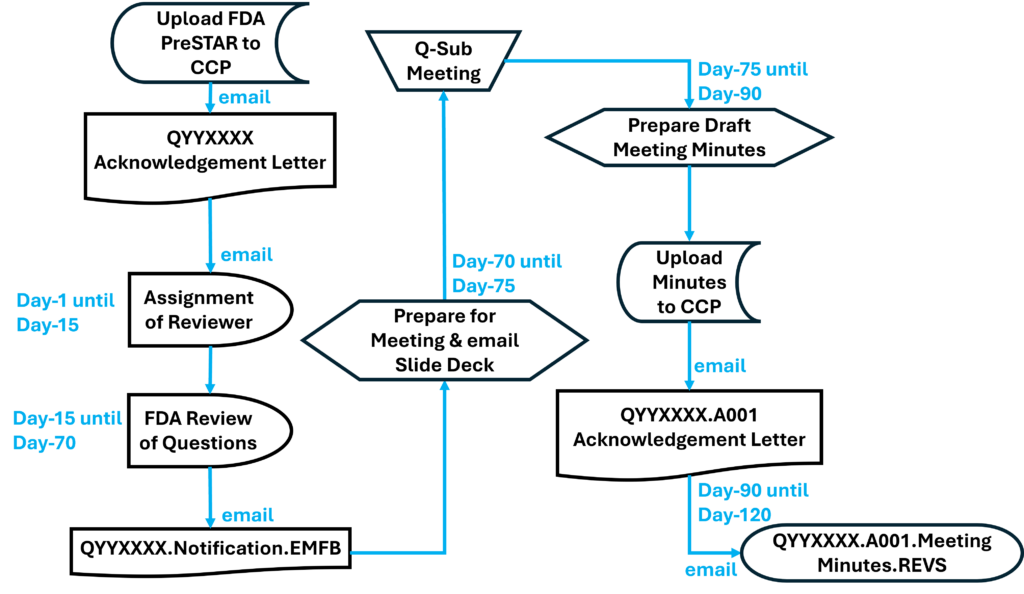

In one of my previous blogs, I explained how the new FDA eSTAR template as a project management tool to verify that all of the section of a 510k submission are complete. Unfortunately, there is no CE Marking equivalent, but you can use your TF/MDR Index as a project management tool when you are constructing a combined plan for a 510k submission and CE Marking. The first step is to create a Index based on a recognized standard (EN standard or ISO standards). Historically we used the GHTF guidance document released by study group 1: N011:2008. When the EU MDR came into force, we added cross-references to the EU MDR in our TF/MDR Index. The GHTF guidance mirrors the format required in Annex III of the new EU MDR. I do not recommend using the NB-MED 2.5.1/rec 5 guidance document. Even though the content is similar to the GHTF guidance, the format is quite different. There is also a new IMDRF guidance document for Essential Principles of Safety and Performance that you should consider referencing.

Project and task management for your combined regulatory plan

If you are going to outsource sections of either submission, the sections should be written and reviewed by someone familiar with both types of submissions. The headers and footers will be unique to the type of submission, but I write the text in Google Docs without formatting for ease of sharing and so I can use my Chromebook.

If you have an in-house team that prepares your 510k submissions and Technical Files, you might consider training the people responsible for each section on the requirements for each type of submission. This eliminates rewriting and reformatting later. I like to assign who is writing each section in a separate column of my project management software. Then I will sort the sections by the expected date of completion. All the safety and performance testing, and any sections requiring validation, will typically be finished at the end of the project. Therefore, it is important to dedicate unique resources to those sections rather than asking one person to write several of those sections. You also will want to make sure any supporting documentation they need is completed early so that the project’s critical path doesn’t change.

Additional training for combining 510k with CE marking

We provide an on-demand 510k course series consisting of 33 FDA eSTAR webinars that you can purchase as a bundle or individually. We also have various training webinars about CE marking on our webinars page.

Combining 510k with CE Marking Submissions Read More »