Supplier Qualification: How To Get The Best Results

In this article, you will learn strategies for better supplier qualification to obtain the highest quality components and services.

Supplier Qualification in ISO 13485:2016

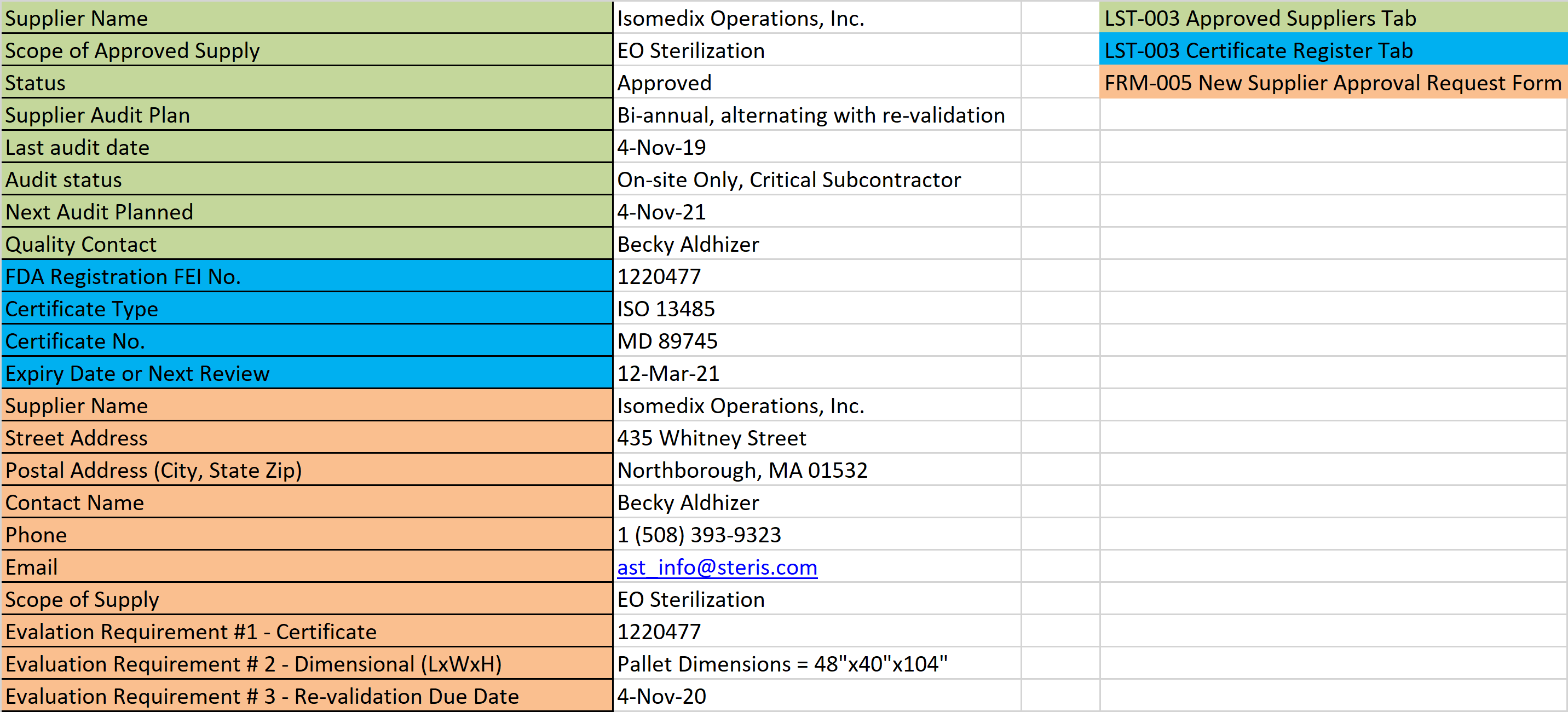

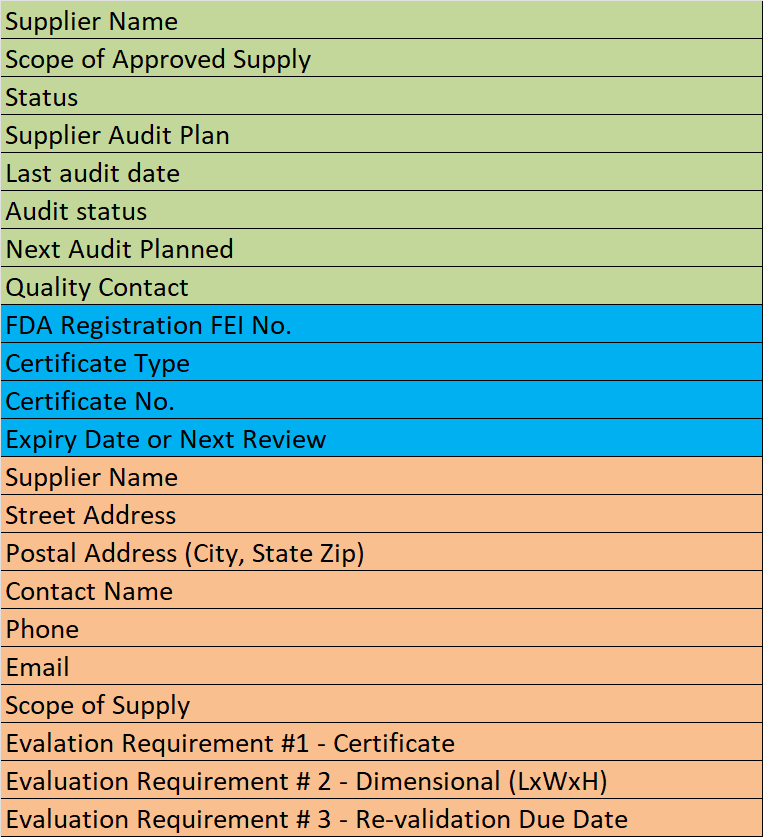

Section 7.4 of EN ISO 13485:2016 states that companies shall “evaluate and select suppliers… based on their ability to supply product in accordance with the organization’s requirements.” Supplier qualification is one of the most important purchasing controls. This requirement is quite vague, but the medical device industry has developed a surprisingly limited number of approaches to address the requirement of this clause.

The most common approach is to ask for some combination of the following:

- ISO certification,

- a copy of the Supplier’s Quality System Manual,

- completion of a Supplier Questionnaire and

- performing a Supplier Audit.

Unfortunately, all four selection criteria are flawed.

ISO Certification

I think the best way to explain why these criteria are flawed is to use an analogy. Let’s compare qualifying a new supplier with recruiting a new employee. ISO certification is sort of like a college degree. You can make some general assumptions about a potential job candidate based upon which school they got their engineering degree from, but the degree is still just a piece of paper on the wall. As the old joke goes:

” What do you call the person that graduated last in their class at medical school?

Doctor

Some registrars have a better reputation than others. Still, the name of the registrar is only as good as its worst client—who had four major nonconformities during their last audit and is about to lose that certificate. To improve this approach to supplier qualification, a potential customer could ask for a copy of the most recent audit report. This information is dependent upon the quality of the audit, but this would be a significant improvement over requesting a copy of the certificate.

![]() CAUTION: Audits are still just samples—tiny samples.

CAUTION: Audits are still just samples—tiny samples.

Again, like degrees, certification must be relevant. ISO 9001:2015 may be a ‘nice-to-have’ quality for potential suppliers. However, it doesn’t hit the mark if you need them to have ISO 13485:2016 certification. Perhaps you need a European Normative version, or A11:2021 as well. For example, sometimes any law degree might be appropriate. Sometimes you specifically need a degree in healthcare law.

This makes it important to establish the criteria for your supplier evaluation early on in the process. Not just because it is required for standard compliance. It is difficult to evaluate a supplier with no guidance on how or what to evaluate them against.

Supplier Quality Manual

The second selection criteria mentioned is The Quality Manual. The Quality Manual is analogous to a resume. The purpose of a resume is two-fold: 1) to provide an interviewer with information, so they can ask the interviewee questions without looking like an idiot, and 2) to provide objective evidence that a company did not illegally discriminate against a candidate that the hiring manager did not like.

I suppose you could argue that the purpose is to help candidates get a job, but in my own experience, less than 10% of resumes submitted result in a job interview—let alone a job offer. The purpose of a Quality Manual is NOT to help a company get new customers. If I am wrong about this, I need to do a much better job of marketing my Quality Manuals in the future.

Some suppliers have the nerve to say that their Quality Manual is proprietary. Humbug! Proprietary information should not be in the Quality Manual. You can copy a manual from another company and edit a few of the details. I will gladly write you a Quality Manual in less than a week that will pass any auditor’s review. You can even buy a Quality Manual online (In fact, Medical Device Academy sells one… Online! POL-001 Quality Manual). This almighty document just explains the intent of the Quality System—which is to conform to the requirements of the ISO Standard. Several auditors will tell you that this can be done in just four pages.

When you request a Quality Manual from a supplier, your primary intent for supplier qualification should be to use this document for planning a supplier audit. Any other purpose is just a waste of your time—unless you need to write a Quality Manual of your own.

Supplier Qualification Questionnaire

The third selection criteria I mentioned was: a supplier questionnaire or supplier survey. Questionnaires are analogous to employment applications. Coincidently, supplier questionnaires are often required by companies when a Quality Manual or ISO Certificate is not available. Do you find the similarities eerie?

Questionnaires are typically 15-20 page documents that someone has plagiarized from a previous employer. I have seen various versions of this questionnaire, but several of them appear suspiciously similar. Hmmm?

I am not sure what the original intent of this type of document was, but I think it was intended to capture detailed information about potential suppliers for a company in the Fortune 500®.

For most companies, 80% of the information on the questionnaire is meaningless. Customer requirements for a supplier are typically few in number and specific to the product or service being purchased. Therefore, please use your MRP system as a template and ensure that the questionnaire answers all the information you need to add the supplier to your system as an approved supplier. You should also have a product or service specification that gives you some more questions to ask.

Ideally, your questionnaire will be organized in the same order that you enter the information into the MRP system. Then this questionnaire will make the data entry easier for the purchasing agent, adding the supplier to the database. Questionnaires and surveys are great, but brevity is next to Godliness.

Supplier Qualification Audits

Finally, we come to the auditor’s favorite—supplier audits. Audits are similar to job interviews. Ideally, you want a cross-functional audit team, and you might need to visit more than once. Unfortunately, most companies cannot afford to audit every supplier. Some companies supplement with remote audits. I guess I think of a desktop audit as a “phone interview.” I use phone interviews to prescreen candidates before I pay more money and waste other people’s time with on-site interviews. Desktop audits of suppliers should not be used as a replacement for an on-site audit, so your supplier quality engineers do not have to spend so many nights at the Hampton Inn.

If audits are your best selection criteria, how can you make the most of your auditing resources? Also, how can you audit for supplier qualification if you only have enough auditors to audit 5% of the approved supplier list? I have the following suggestion: “Start at the end.” You might consider reviewing our article on hiring an auditor.

ISO 13485:2016 Clauses 8.5.2 / 8.5.3 CAPA

What I mean by this cryptic, four-word phrase is that auditors should start at the end of the ISO Standard with sections 8.5.2 & 8.5.3 (Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) Process). This is the heart of a Quality System. If you disagree, remember that FDA inspectors are required to look at the CAPA system during every Level 1 inspection. Registrars also look at the CAPA process during every assessment—not just the certification audits. The purpose of the CAPA process is to fix problems, so they don’t come back—ever.

If you think that a new supplier is never going to make a mistake, you might as well quit looking. You want suppliers with strong CAPA systems. If a supplier has a strong CAPA system, problems will be fixed quickly and permanently. To sample the CAPA process, an auditor only needs the following: 1) the CAPA procedure(s), 2) the CAPA log(s), and 3) a handful of completed CAPA records—selected not so randomly from the log(s). This can all be done remotely in a desktop audit. If suppliers are resistant to giving you the log or actual records, ask them to redact any sensitive information. If you have executed a nondisclosure agreement, the supplier should agree with this approach.

ISO 13485:2016 Clause 8.4 Analysis of Data

Working from the back of the Standard, the next process to sample is clause 8.4 (Analysis of Data). There are four requirements of this clause. If the company has a requirement for customer satisfaction to be measured (ISO 9001:2008 section 8.4a), this is a great place to focus. There are also requirements to look at the trend of product conformity (8.4b), process metrics (8.4c), and trends in supplier data—such as on-time delivery and raw material nonconformities (8.4d). The quality of the analysis will tell an auditor as much about the company as the data itself. This process audit can also be performed remotely as a desktop audit.

A lot has changed since this article was first written. For example, if your potential supplier isn’t using ISO 9001:2015 you may want to verify that other areas of their quality management system aren’t outdated as well.

ISO 13485:2016 Clause 8.3 Control of Nonconforming Materials

Clause 8.3, Control of Nonconforming Materials, is the third area to look at. To sample this area, you will need the “Holy Trinity” again: 1) procedure, 2) log, and 3) records. In this desktop audit, you want to look very closely at any nonconforming materials that are reworked or accepted “as is” (i.e., UAI). Either of these two dispositions should be ULTRA-RARE. Everything else should be processed efficiently as scrap or returned to the Vendor (i.e., – RTV).

If a potential supplier passes all three “tests” described above, you are ready to address clause 8.2.4—Monitoring & Measurement of Product. In this section, there is a requirement to maintain records of product releases and to verify that product requirements are met. for supplier qualification, if you think you can effectively audit this by paperwork alone, the supplier is a good candidate for “desktop only.” However, if the lot release paperwork, batch record, or Device History Record (DHR) is a 50-page tome—then you better make your flight plans.

The good news is that very few suppliers will pass the first three tests and implode during the on-site audit. Also, with three process audits complete, you should be able to reduce the duration of your on-site audit. Finally, for low-risk suppliers, you have a strong basis for provisional approval of suppliers to proceed with prototype runs before you schedule an on-site audit. If you need a procedure for supplier qualification, please check our Supplier Quality Management Procedure (SYS-011).

For more information on supplier controls, quality systems, auditing, and regulatory submissions visit our YouTube Channel!

Supplier Qualification: How To Get The Best Results Read More »