Benefit-Risk Analysis – ISO 14971:2019, Clause 7.4

This article explains the requirements for a benefit-risk analysis as defined in ISO 14971:2019, Clause 7.4 and in the EU regulations.

What is a benefit-risk analysis?

A benefit-risk analysis is one of the risk management activities explained in ISO 14971:2019. Specifically, this requirement is found in clause 7.4 of the medical device risk management standard. Originally, the requirement was described as “risk-benefit analysis” in the second edition of the medical device risk management standard. The US FDA revised their policies for novel devices (e.g., De Novo and PMA submissions) to emphasize that novel devices must demonstrate clinical benefits or they will not be approved. Therefore, the US FDA revised the wording to place the word “benefit” before the word “risk.” This approach and the revised wording was adopted by the committee that was drafting the third edition of the ISO 14971 standard. The wording was also adopted by 2012 European version of the standard, the EU MDR, and EU IVDR. In general, this risk management activity involves a semi-quantitative comparison of clinical benefits with risks of harm. The ISO 14971 standard indicates that if risks are unacceptable, a device can still be recommended for commercial release by a design team if the clinical benefits outweigh the risk of harm.

Is there discretion as to whether a benefit-risk analysis needs to take place?

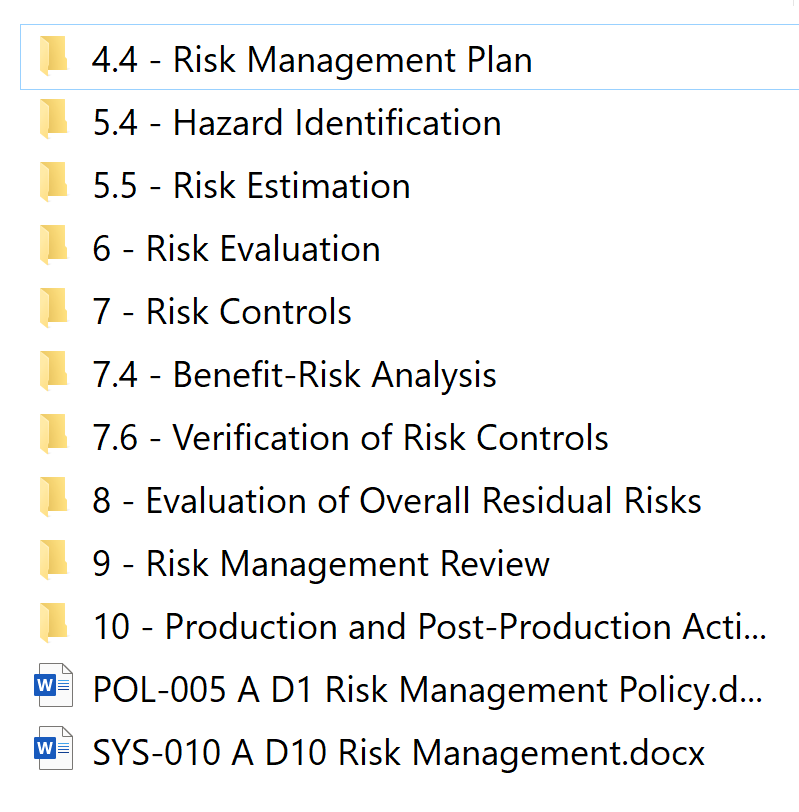

The ISO 14971 Standard implies that a benefit-risk analysis is only required if the risks of harm exceed a threshold of acceptability. In the ISO/TIR 24971:2020 guidance, the committee clarified that acceptability of risk must be documented in a risk management policy (see Annex C2 for guidance and recommended content for a risk management policy). However, the EU MDR and IVDR regulations require that you perform a benefit-risk analysis for each individual risk and overall residual risk of a medical device. This is stated in Annex I, the General Safety and Performance Requirements. Therefore, if your company distributes devices only in the USA that are Class 1 or Class 2, and the submission type is not a De Novo or Humanitarian Device Exemption (HDE), then you are only required to perform a benefit-risk analysis if the risks of harm are unacceptable. If the device requires a De Novo application, and HDE, or a Class 3 PMA, then you are required to submit a benefit-risk analysis to the FDA in your premarket submission. For companies that distribute devices in Europe, the companies do not have discretion with regard to performing a benefit-risk analysis and they must include it in the risk management file. Since some of Medical Device Academy’s clients are seeking approval for a De Novo, HDE, or PMA, or the companies are distributing in the EU, our risk management procedure does not allow discretion regarding whether a benefit-risk analysis needs to be performed. The template we created for this is TMP-034 in SYS-010.

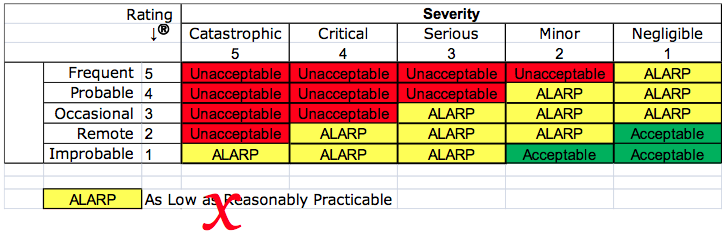

As Low As Reasonably Practicable (ALARP)

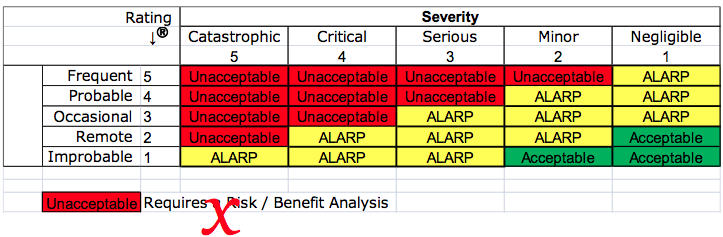

Your company may have a risk management procedure which includes a matrix for severity and probability. The matrix is probably color-coded to identify red cells as unacceptable risks that require a benefit-risk analysis, yellow cells that are ALARP, and green cells that are acceptable. This practice was criticized in 2012 by the European Commission. “Acceptability” of risk is no longer permitted using the principles of “ALARP.”

The EU regulations require that the analysis of benefit-risk ratios be performed for each risk and all residual risks—not just the risks you identify as unacceptable. However, the EU regulations also do not permit that financial considerations be used as part of the determination of risk acceptability. Financial considerations are implied in the ALARP principle. To clarify this, notes were added to ISO 14971:2019, the guidance on risk acceptability was moved to ISO/TIR 24971:2020, and the concept of ALARP was removed from the risk management standard and the guidance. Therefore, we recommend that your risk management policy reference the need for a benefit-risk analysis, regulatory requirements, the requirements of recognized medical device standards, and stakeholder requirements–not ALARP.

Integrating benefit-risk analysis into your design process

The best way to integrate benefit-risk considerations into your design process is by performing a clinical evaluation. In addition to using clinical literature, clinical study data, and post-market surveillance as inputs for your clinical evaluation, your company should also be using residual risks as inputs to the evaluation. The clinical evaluation should be used to assess the significance of these residual risks, and verify that there are not any risks identified in the clinical evaluation that were not considered in the risk analysis.

In order to document that your company has performed a benefit-risk analysis for each residual risk, you will need to reference the risk management report in the clinical evaluation and vice-versa. Both documents will need to provide traceability to each risk identified in the risk analysis, and conclusions of risk acceptability will need to be based upon the conclusions of the clinical evaluation.

Once your device is commercialized, you will need to update the clinical evaluation with adverse events and other post-market surveillance information. As part of updating clinical evaluations, you will need to determine the acceptability of the risk when weighed against the clinical benefits. These conclusions will then need to be updated in the risk management report—including any new or revised risks.

If you are interested in benefit-risk analysis training, we offer a benefit-risk analysis webinar as part of our 510(k) course series.

Benefit-Risk Analysis – ISO 14971:2019, Clause 7.4 Read More »