Audit Scheduling Options: Are you running out of time?

An auditor quit, and you need some audit scheduling options to complete your audit schedule by the end of the year. Sound familiar?

What will happen if you don’t finish your audit schedule by December 31?

It’s October 14, and there are 78 days left in 2025. You have four supplier audits and three internal audits to complete. Unfortunately, one of the lead auditors on your team just resigned. It will probably take a couple of months to fill the position. Top management wants to know how you are going to complete the audit schedule on time. Before you panic, ask yourself one question: “What will happen if you don’t finish your audit schedule by December 31?”

Consequences of audit failure?

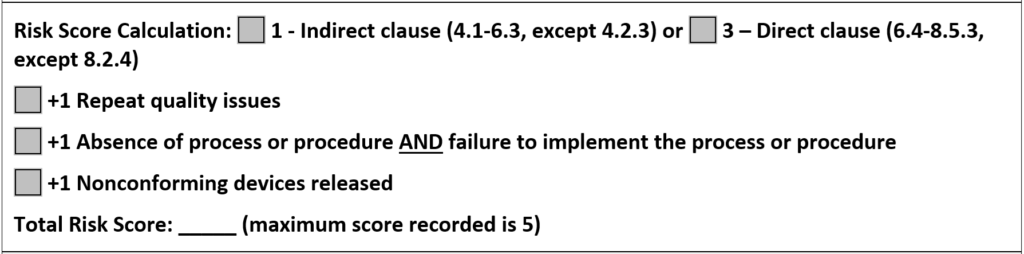

Most companies fear receiving an FDA 483 inspection observation or a nonconformity from a third-party auditor because they did not complete their audit schedule as planned. This might happen, but what are the consequences? During opening and closing meetings, we remind clients that there is only one possible outcome of any audit:

Opening a CAPA takes time and resources, but top management should never make the situation worse by reprimanding (or firing) someone because of an audit finding. If an employee is not doing their job, the quality system’s monitoring and measurement should identify the problem before the audit. Disciplinary action is not a corrective action. Top Management is responsible for providing the resources to maintain the effectiveness of the quality system. Regardless of why the audit schedule was not completed, the quality system needs to be robust enough to withstand the resignation of a single employee. Top management needs to temporarily reassign the former employee’s responsibilities to other employees and/or seek outside help. It may even be necessary to reschedule some activities, such as audits. Top management needs alternatives, including audit scheduling options, so they can create a transition plan while a replacement is recruited or promoted from within. That transition plan also needs to be documented.

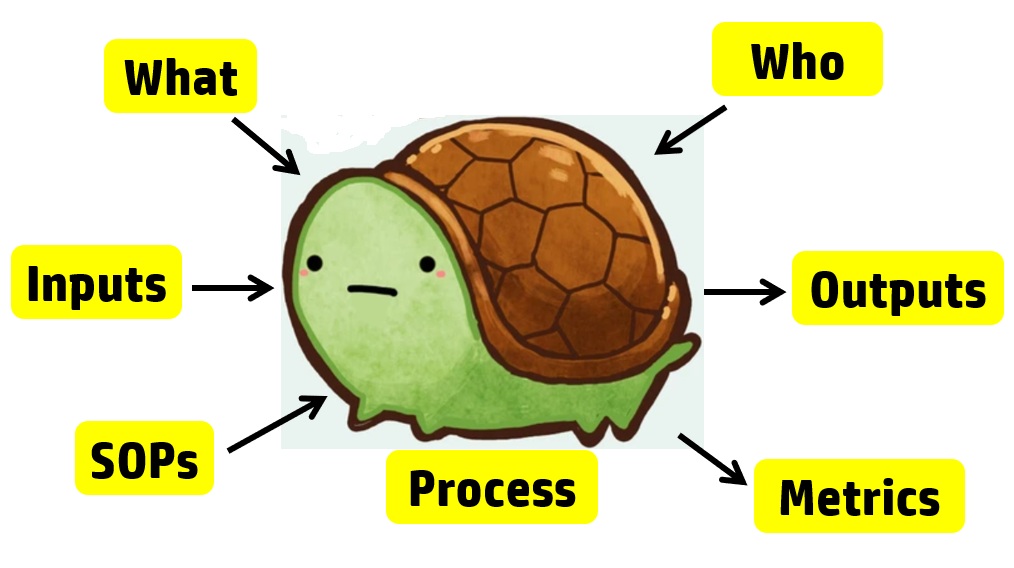

Using a risk-based approach to audit scheduling

Not all audits are equally important. If you have seven audits (i.e., two second-party and three first-party audits) left to complete, first evaluate the importance of each audit and assess the risks of delaying any of them. Any routine audits can be rescheduled. Just update your audit schedule to reflect new dates for the routine audits. Non-routine audits include: 1) supplier qualification, 2) investigation of supplier nonconformities, 3) CAPA effectiveness checks, and 4) investigation of internal processes with quality problems. If your incomplete scheduled audits were non-routine, they should be prioritized. Below is a list of audit scheduling options to consider:

- Consider other ways to qualify a new supplier than auditing (e.g., check references, review certifications, rely on a third-party audit report)

- Hire a consultant to conduct audits (both first and second party audits)

- Consider other ways to verify the effectiveness of a CAPA (e.g., quantitative acceptance criteria in a process validation report or process metrics compared before and after implementation of corrective actions)

- Place the product associated with suppliers or processes under quarantine until audits can be conducted.

- Conduct remote audits or reduce audit duration to complete them with fewer resources.

There are some fantastic cartoons and jokes about doing more with less, but if you intend to complete seven audits before the end of the year, you might need some help.

Training more auditors can increase your audit scheduling options.

Seventy-eight days might not be enough time to train a new auditor and complete all seven audits, but you can complete lead auditor training, and the newly trained auditor can help. If you are assigning a new auditor to conduct an audit, we recommend assigning them to conduct virtual audits via teleconference recordings (e.g., Zoom). These audits could be supplier audits or internal audits. This would allow an experienced lead auditor to review the recordings after the audit is completed. If the experienced auditor identifies any gaps or audit trails that should have been pursued, they can review the recordings with the auditor-in-training to identify follow-up actions if needed and to help them learn from their mistakes before their next audit. Historically, new lead auditors required a “shadow” to observe them during training. Today, we can use virtual auditing, and the observer’s feedback is actually better.

What if you need more auditors?

As we mentioned above, you can train new lead auditors. However, if you have one or more auditors who are qualified as lead auditors, you can schedule team audits instead. It takes less time to train an audit team member than it does to train a lead auditor. In a team audit, the audit can be completed more quickly. A team audit is an excellent solution for internal audits, because supplier audits usually require a single auditor. Adding a second auditor to a supplier audit would not save significant time, because travel to the supplier is still required. For an internal audit, the audit duration can be reduced from 3 or 4 days to 1.5 or 2 days. It is also possible to conduct partial internal audits that take less than a day.

Consider changing the duration of your audit schedule.

The last quarter of the year is historically hectic for everyone — especially quality assurance auditors. Therefore, we try to avoid scheduling audits near the end of the year. It’s much easier to schedule audits in the first quarter of the year (i.e., January – March). Another audit scheduling option is to create an 18-month schedule rather than a 12-month one. As stated in the YouTube video embedded above, an 18-month audit schedule ensures that several months are remaining in your audit schedule at any time.

Did you consider scheduling remote supplier audits?

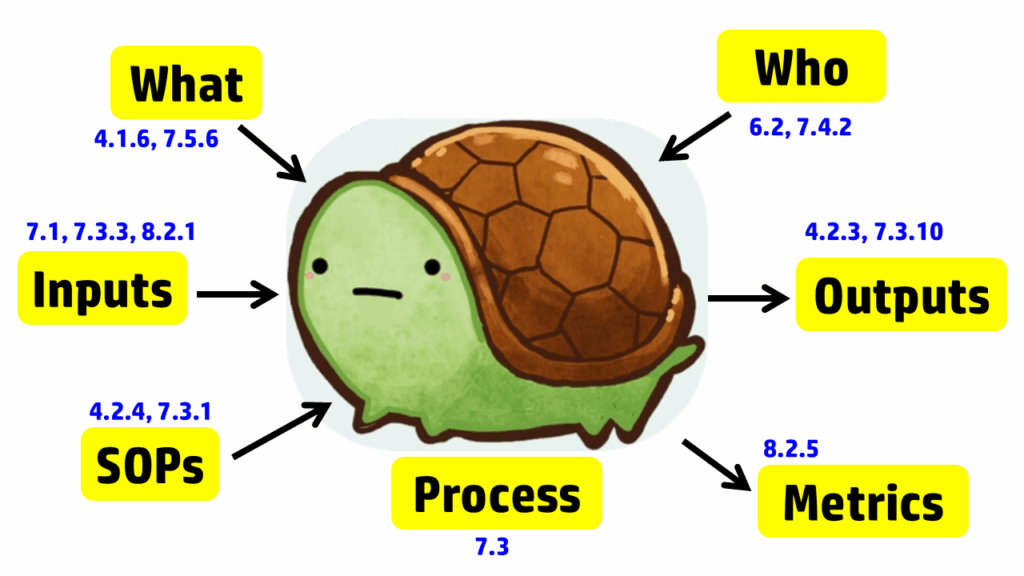

If you were only planning on-site supplier audits, considering remote supplier audits expands your audit scheduling options. Remote audits are always permitted for first- and second-party audits, but they are most effective when on-site audits of the supplier have been conducted previously. However, a remote audit is not the same as asking a supplier to complete a survey. ISO 19011:2018 provides guidance on remote auditing in the annexes. For a remote audit, you should still sample the same number of records—if not more. You should conduct interviews by phone, Zoom, or some similar technology. You should analyze any available data to help identify which processes appear to be effective and which need improvement. Suppose you are performing a remote audit for the first time. In that case, I recommend focusing on the same processes you would not generally audit in a conference room, rather than on those you would typically audit where they occur—such as production controls. Regardless of which method you use, you should always request data.

Metrics to consider for your quality auditing process

In parallel with your efforts to catch up on your audit schedule, top management should consider implementing a process metric for “on-time delivery” of audits and audit reports. This is an effective metric for managing an audit program, and it is especially important to monitor it when you have turnover among trained lead auditors. If any auditor or audit report is delivered late, investigate the reasons for the audit being overdue. If the occurrence was preventable, then I recommend initiating additional countermeasures to improve the audit process. This might include opening a CAPA. This will have two effects. First, your third-party auditors will see that you have identified the problem and taken appropriate corrective action(s). If you also discuss this during a Management Review, this information can be used effectively to change the grading of an audit finding to a “minor” or to potentially eliminate the finding altogether. Second, it will ensure that this doesn’t occur again.

Audit Scheduling Options: Are you running out of time? Read More »