Auditing Design Controls – 7 Step Process

This blog reviews seven steps for effectively auditing design controls utilizing the ISO 13485 standard and process approach to auditing.

Third-party auditors (i.e., – a Notified Body Auditor) don’t always practice what we preach. I know this may come as a huge shock to everyone, but sometimes we don’t use the process approach. Auditing design controls is a good example of my own failure to follow was it true and pure. Instead, I use NB-MED 2.5.1/rec 5 as a checklist, and I sample Technical Files to identify any weaknesses. The reason I do this is that I want to provide as much value to the auditing client as possible without falling behind in my audit schedule.

Often, I would sample a new Technical File for a new product family that had not been sampled by the Technical Reviewer yet. My reason for doing this is that I could often find elements that are missing from the Technical File before the Technical Reviewer saw the file. This gives the client an opportunity to fix the deficiency before submission and potentially shortens the approval process. Since NB-MED documents are guidance documents, I could not write the client up for a nonconformity, unless they were missing a required element of the M5 version of the MDD (93/42/EEC as modified by 2007/47/EC). This is skirting the edge of consulting for a third- party reviewer, but I found it was a 100% objective way to review Technical Files. I also found I could review an entire Technical File in about an hour.

What’s wrong with this approach to auditing design controls?

This approach only tells you if the elements of a Technical File are present, but it doesn’t evaluate the design process. Therefore, I supplemented my element approach with a process audit of the design change process by picking a few recent design changes that I felt were high-risk issues. During the process audit of the design change process, I sampled the review of risk management documentation, any associated process validation documentation, and the actual design change approval records. If I had time, I looked for the following types of changes: 1) vendor change, 2) specification change, and 3) process change. By doing this, I covered the following clauses in ISO 13485:2016: 7.4 (purchasing), 7.3.9 (design changes), 7.5.6 (process validation), 7.1 (risk management), and 4.2.5 (control of records).

So what is my bastardized process approach to auditing design controls missing? Clauses 7.3.1 through 7.3.10 of ISO 13485:2016 are missing. These clauses are the core of the design and development process. To address this, I would like to suggest the following process approach:

Step 1 – Define the Design Process

Identify the process owner and interview them. Do this in their office–not in the conference room. Get your answers for steps 2-7 directly from them. Ask lots of open-ended questions to prevent “yes/no” responses.

Step 2 – Process Inputs

Identify how design projects are initiated. Look for a record of a meeting where various design projects were vetted and approved for internal funding. These are inputs into the design process. There should be evidence of customer focus, and some examples of corrective actions taken based upon complaints or service trend analysis.

Step 3 – Process Outputs

Identify where Design History Files (DHF) are stored physically or electronically, and determine how the DHF is updated as the design projects progress.

Step 4 – What Resources

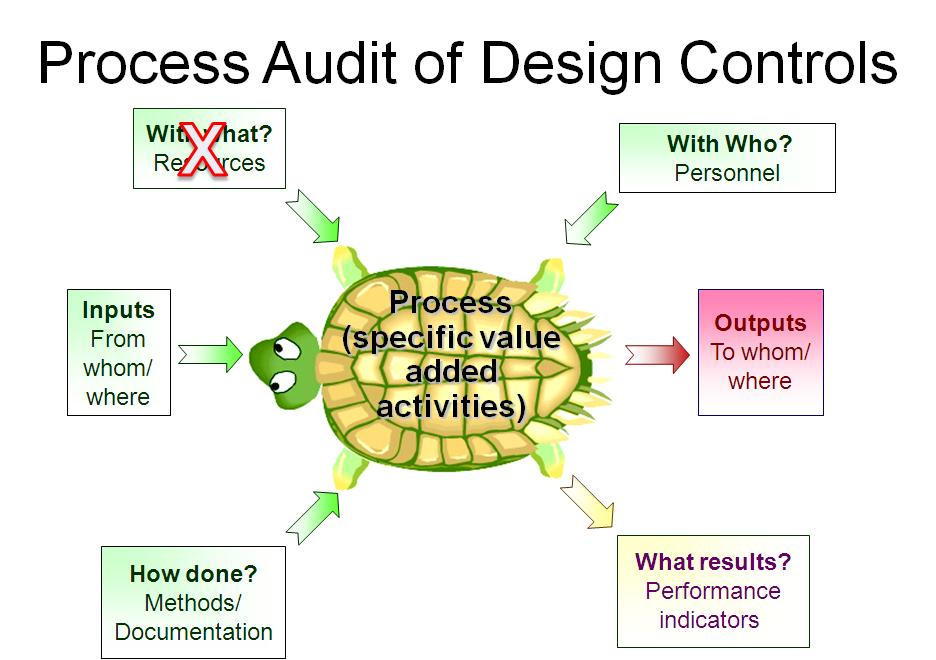

This is typically the step of a process audit where their auditor needs to identify “what resources” are used in the process. However, only companies that have software systems for design controls have resources dedicated to Design and Development. I have indicated this in the “Turtle Diagram” presented above.

Step 5 – With Whom, Auditing Training Records

Identify which people are assigned to the design team for a design project. Sometimes companies assign great teams. In this case, the auditor should focus on the team members that must review and approve design inputs (see Clause 7.3.2) and design outputs (see Clause 7.3.3). All of these team members should have training records for Design Control procedures and Risk Management procedures.

Step 6 – Auditing Design Controls Procedures and Forms

Identify the design control procedures and forms. Do not read and review these procedures. Auditors never have the time to do this. Instead, ask the process owner to identify specific procedures or clauses within procedures where clauses in the ISO Standard are addressed. If the process owner knows exactly where to find what you are looking for, they’re training was effective, or they may have written the procedure(s). If the process owner has trouble locating the clauses you are requesting, spend more time sampling training records.

Step 7 – Process Metrics

Ask the process owner to identify some metrics or quality objectives they are using to monitor and improve the design and development process. This is a struggle for many process owners–not just design. If any metrics are not performing up to expectations, there should be evidence of actions being taken to address this. If no metrics are being tracked by the process owner, you might review schedule compliance.

Many design projects are behind schedule, and therefore this is an important metric for most companies. Now that you have completed your “Turtle Diagram,” if you have more time to audit the design process, you can interview team members to review their role in the design process. You could also sample-specific Technical Files as I indicated above. If you are performing a thorough internal audit, I recommend doing both. To learn more about using the process approach to auditing, you can register for our webinar on the topic.

Auditing Design Controls – 7 Step Process Read More »