Regulatory pathway & MedTech investor pitch deck

This article explains how to prepare a regulatory pathway analysis and an investor pitch deck for a MedTech startup.

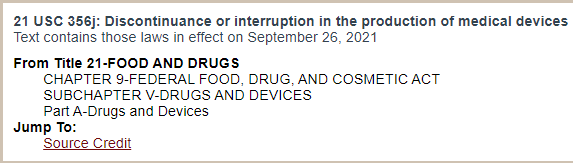

Regulatory Pathway Case Study

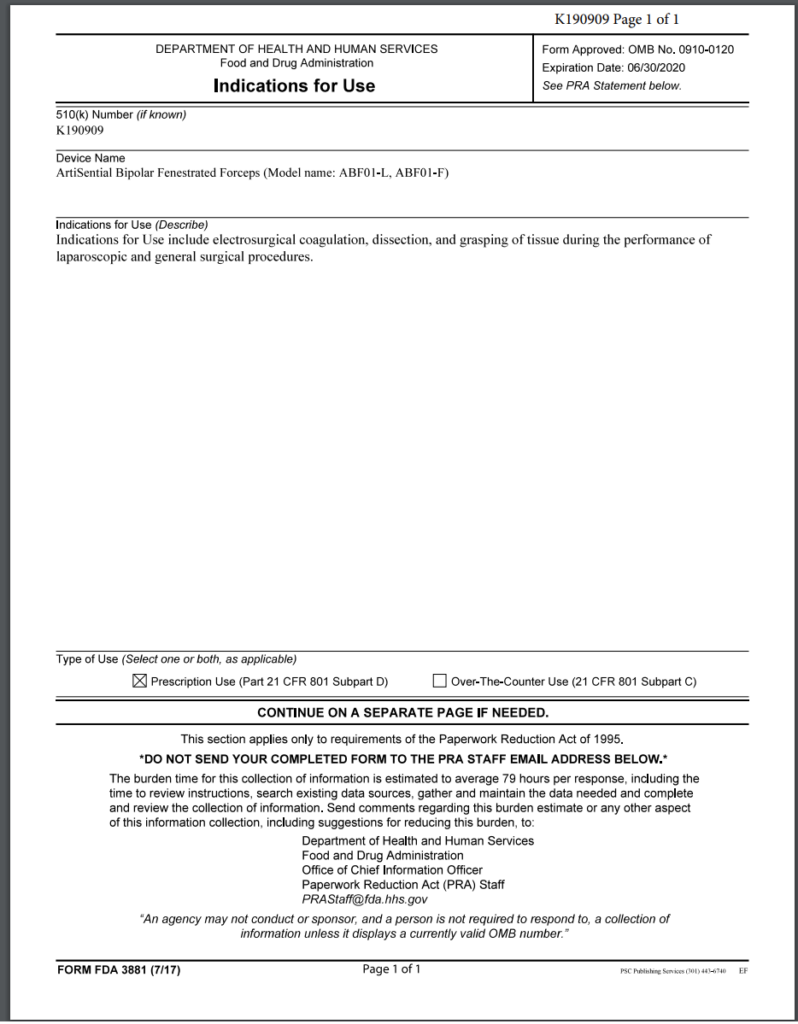

This article uses two case study examples to explain how to determine the correct regulatory pathway for your medical device through the US FDA. One of the case study examples is bipolar forceps for use with an electrosurgical generator. A picture of the forceps is provided above. The second case study example is resin for repairing dentures. Rather than providing the second example in detail, we provided the information as we would summarize it in an investor pitch deck. You can also download the pitch deck template at the end of the article.

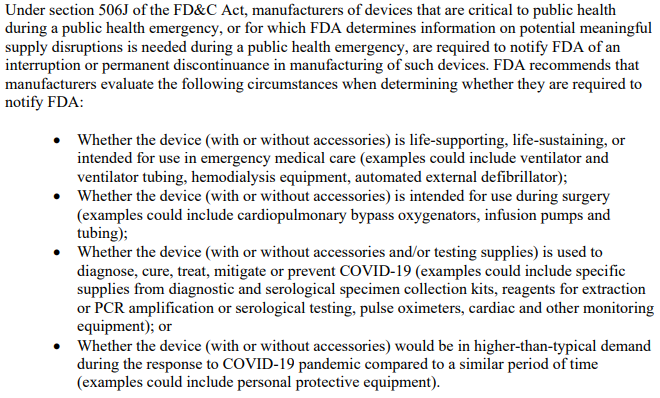

What is the regulatory pathway for your device?

Every consultant likes to answer this type of question with the answer, “It depends.” Well, of course, it depends. If there were only one answer, you could Google that question, and you wouldn’t need to pay a regulatory consultant to answer the question. A more helpful response is to start by asking five qualifying questions:

- Does your product meet the definition of a device?

- What is the intended purpose of your product?

- How many people in the USA need your product annually?

- Is there a similar product already on the market?

- What are the risks associated with your product?

The first question is important because some products are not regulated as medical devices. If your product does not diagnose, treat, or monitor a medical condition, it may not be considered a device. For example, the product might be considered a general wellness product or clinical decision support software. In addition, some products have a systemic mode of action, and these products are typically categorized as a drug rather than a device–even if the product includes a needle and syringe.

The intended purpose of the device directly impacts the product classification and regulatory pathway

The intended purpose of a product is the primary method used by the US FDA to determine how a product is regulated. This also determines which group within the FDA is responsible for reviewing your product’s submission. The US regulations use the term “intended use” of a device, but the decision is based upon the “indications for use,” which are more specific. To understand the difference, we created a video that explains it.

Devices intended for very small patient populations fall into a rare regulatory pathway.

Even regulatory consultants sometimes forget to ask how many people need your product annually, but population size determines the regulatory pathway. Any patient population of less than 8,000 patients annually in the USA is eligible for a humanitarian device exemption, which offers a special regulatory pathway and pricing constraints. If your product is intended for a population of <8,000 people annually, your device could qualify for a humanitarian device exemption, and the market is small enough that there may not be any similar products on the market.

If your device is equivalent to a competitor product, you may be eligible for 510(k) clearance.

If similar products are already on the US market, determining the regulatory pathway is much easier. We can look up the competitor product(s) in the FDA’s registration and listing database. In most cases, you must follow the same pathway your competitors took, and the FDA database will tell us your regulatory pathway.

The FDA divides devices into three risk classifications (i.e., Class 1, 2, and 3)

If all the products on the US market have different indications for use, or the technological characteristics of your product differ from those of other devices, then you need to categorize the risks associated with your product. For low-risk devices, general controls may be adequate. For medium-risk devices, the FDA requires special controls. For the highest-risk devices, the FDA typically requires a clinical study, a panel review of your clinical data, and pre-market approval (PMA).

What is the US FDA regulatory pathway for your device?

The generic term used for regulator authorization is “approval,” but the US FDA reserves this term for Class 3 devices with a Premarket Approval (PMA) submission. The reason for this is that only these submissions include a panel review of clinical data to support the safety and effectiveness of the device. Approval is limited to ~30 devices each year, and approximately 1,000 devices have been approved through the PMA process since 1976, when the US FDA first began regulating medical devices.

Most Class 2 devices are submitted to the FDA as Premarket Notifications or 510k submissions. This process is referred to as “510k clearance,” because clinical data is usually not required with this submission, and there is no panel review of safety and effectiveness data. A 510 (k) was originally planned as a rare pathway that would only be used by devices that are copies of other devices already sold on the market. However, the 510 (k) pathway became the de facto regulatory pathway for 95% or more of devices sold in the USA.

For moderate and high-risk devices that are intended for rare patient populations (i.e., <8,000 patients per year in the USA), the humanitarian device exemption process is the regulatory pathway.

Class 1 devices typically do not require a 510k submission; most of these devices are exempt from design controls, and some are exempt from quality system requirements. These devices still require listing on the FDA registration and listing database; however, there is no FDA review to ensure that you have correctly classified and labeled Class 1 devices.

How do you find a predicate for your 510k submission?

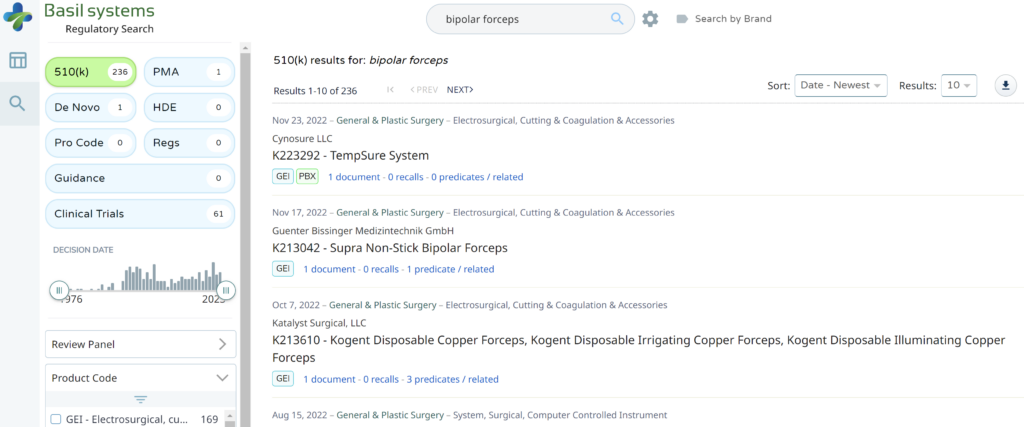

As stated above, one of the most critical questions is, “Is there a similar product already on the market?” For our example of bipolar forceps, the answer is “yes.” There are approximately 169 bipolar forceps that have been 510k cleared by the FDA since 1976. If you are developing new bipolar forceps, you must prepare a 510k submission. The first step of this process is to verify that a 510k submission is the correct pathway and to find a suitable competitor product to use as a “predicate” device. A predicate device is a device that meets each of the following criteria:

- it is legally marketing in the USA

- it has indications for use that are equivalent to your device

- the technological characteristics are equivalent to your device

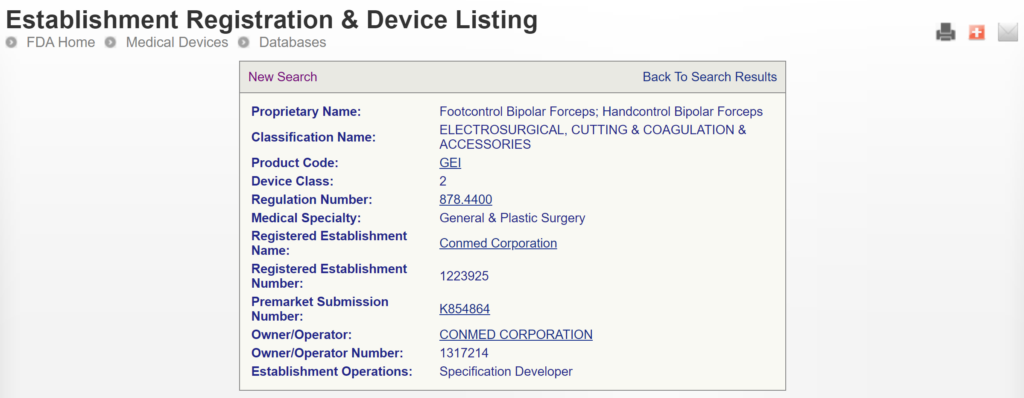

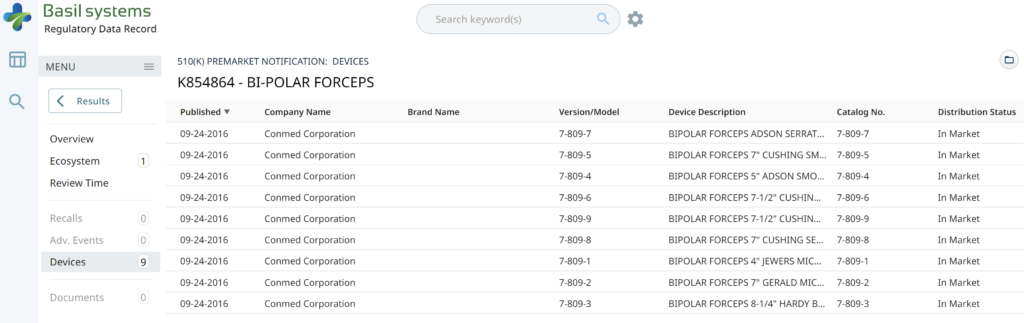

There are two search strategies we use to verify the product classification of a new device and to find a suitable predicate device. The first strategy is to use the free, public databases provided by the FDA. Ideally, you instantly think of a direct competitor that sells bipolar forceps for electrosurgery in the USA (e.g., Conmed bipolar forceps). You can use the registration and listing database to find a suitable predicate in this situation. First, you type “Conmed” into the database search tool for the name of the company, and then you type “bipolar forceps” in the data search tool for the name of the device.

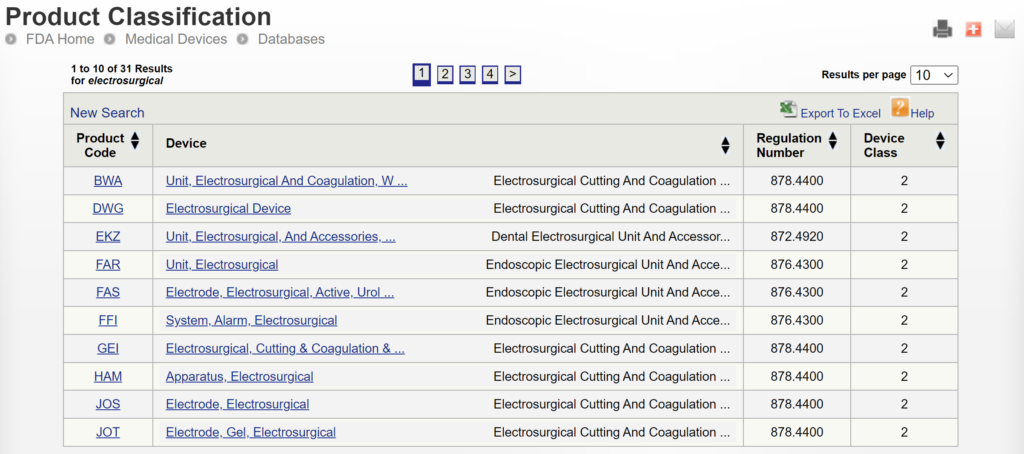

If you are unaware of any competitor products, you will need to search using the product classification database instead. Unfortunately, this approach will result in no results if you use the terms “bipolar” or “forceps.” Therefore, you will need to be more creative and use the word “electrosurgical,” which describes a broader product classification that encompasses both monopolar and bipolar surgical devices, which come in various sizes and shapes, including bipolar forceps. The correct product classification is seventh out of 31 search results.

The most significant disadvantage of the FDA databases is that they can only be searched separately. The search is also a Boolean-type search rather than using natural language algorithms that we all take for granted. The second strategy is to use a licensed database (e.g., Basil Systems).

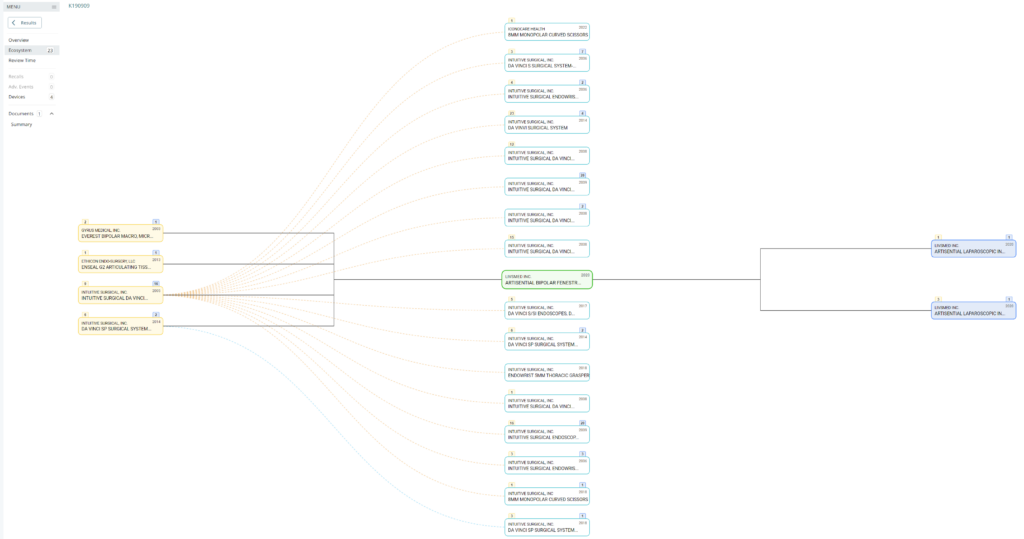

Searching these databases is more efficient, and the software will provide additional information that the FDA website does not offer, such as a predicate tree, review time, and models listed under each 510k number are provided below:

What does the predicate tree look like for the predicate device you selected?

How to create an investor pitch deck.

A pitch deck is brief. You want to generate interest and encourage questions from the audience. If the audience specifies a time limit, practice your pitch until you can “hit the post.” For Project MedTech, the target is a 6-minute pitch. Replace the image with your own and be creative with your image cropping. Replace our logo with your own. Replace “Medical Device Academy, Inc.” with your company name. Replace “MedTech Pitch Deck” with the name of the group or person you are pitching.

Management Team

No need to label every slide. It should be obvious that this is your management team. Remember to focus on the relevant background, rather than everything. It’s just a brief summary, and this might be an opportunity to use the morph transition function to zoom in on each photo, name, and title as you say something NOT IN THE SLIDE about each of the people on the team. Consider a little self-deprecating humor (i.e., how each of them compensates for your weaknesses). The presenter does not need to talk about themselves because the quality of the pitch speaks volumes.

Competitor Devices

In general, use very few words. The focus of the presentation should be on the presenter, not reading the slides. After all, you submit a slide deck, but you want the opportunity to pitch investors. Black backgrounds with a few high contrast words is easy to read and won’t detract from the you—the presenter. In this slide, “a story” is highlighted to emphasize an important point and to show you how a dash of yellow draws attention to what’s important. “[Dentures]” should be replaced by the common name for your type of device. Don’t make potential investors think too hard. Your selection of pictures will help demonstrate that you know who your competitors are (i.e., competitive analysis). “We have no competition” is a mistake, because that means the market doesn’t exist yet, or it is too small to attract any competitors.

Subject Device

The ideal picture will immediately explain what makes your device unique and show investors what problem(s) you solved. If you can demonstrate this quickly in a presentation or video, do it. Vocal variety can also be used very effectively here by quietly telling the audience how your product is unique (i.e., it’s a secret). Concluding that secret with a silent 6-second pause is LOUDER than yelling. For example, you could whisper: “Our dentures won’t fall out.”

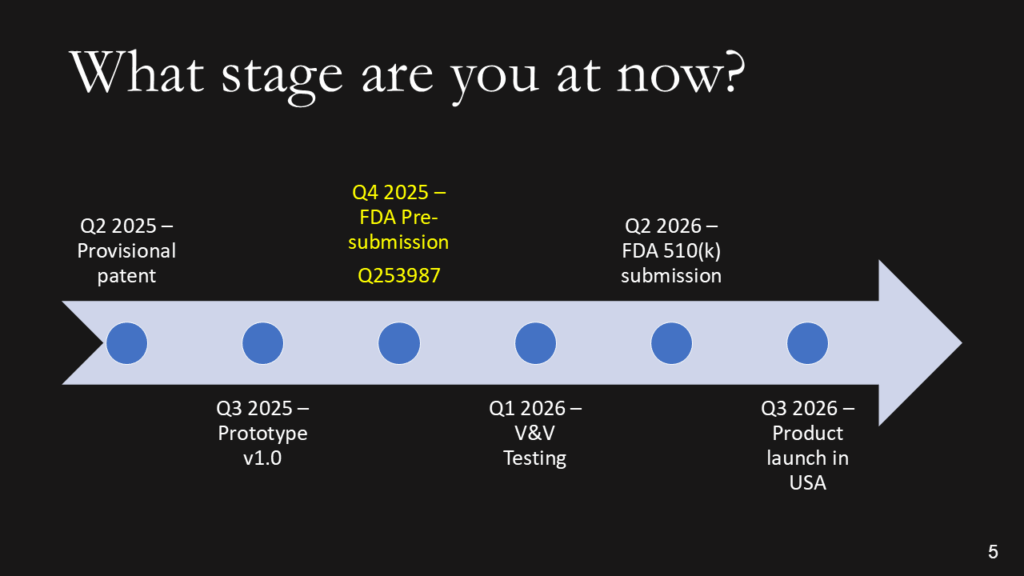

What stage of development is your device?

We don’t want the history of the universe. We need to know where you are, when you plan to submit to the FDA, and when you expect to start generating revenue. Adding the date of a patent or provisional patent with the document # is a clever way to say that you have a patent without wasting time with the words. The addition of the Q-sub number adds credibility. If you are conducting clinical studies, it is essential to note the cost of these studies, as they can be significant. If you are prepared to identify reimbursement milestones, add them. Resist building this out to two slides if you are a start-up. You should have revenues already if you need two slides.

After providing a timeline with regulatory milestones, investors will expect you to explain the regulatory pathway of your device.

How do you create a regulatory pathway strategy for medical devices?

The best strategy for obtaining 510k clearance is to select a predicate device with the same indications for use that you want and was recently cleared by the FDA. Therefore, you will need to review FDA Form 3881 for each of the potential predicate devices you find for your device. In the case of the bipolar forceps, there are 169 devices to choose from; however, FDA Form 3881 is not available for 100% of those devices, as the FDA database only displays FDA Form 3881 and the 510(k) Summary for devices cleared since 1996. Therefore, you should select a device cleared by the FDA within the past ten years, unless there are no equivalent devices with recent clearance.

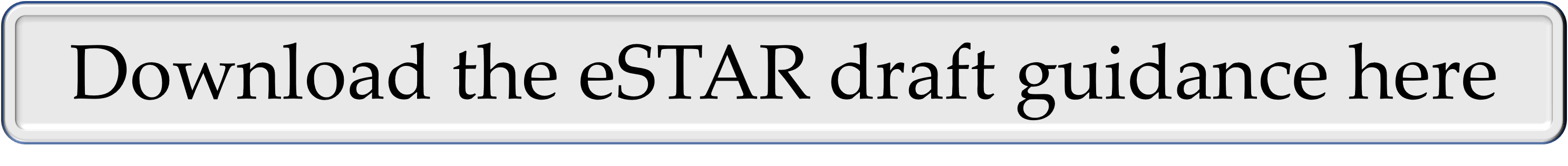

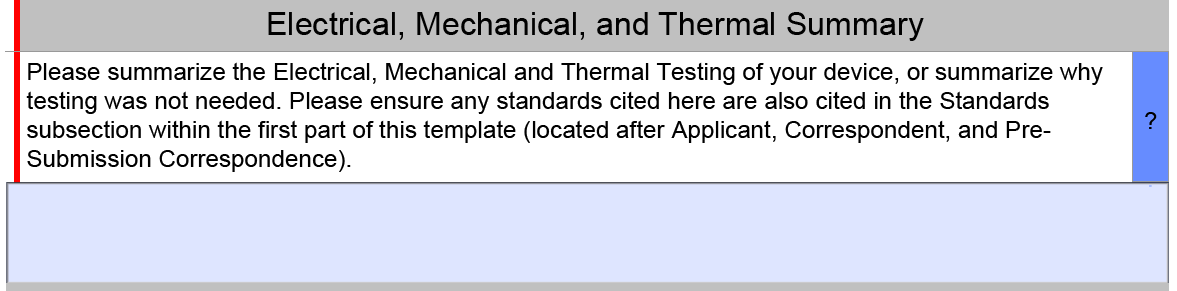

Note: The FDA no longer uses FDA Form 3881 in the FDA PreSTAR or eSTAR, but a similar section exists in both submission templates.

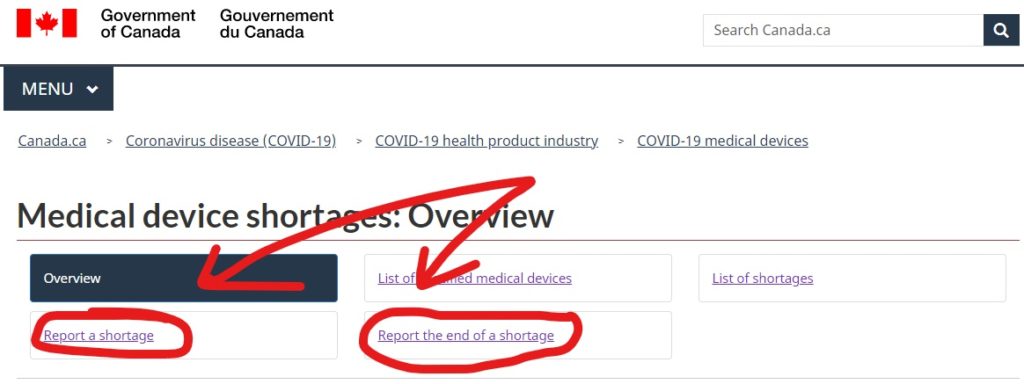

In addition to identifying the correct product classification code for your device and selecting a predicate device, you will also need to develop a testing plan for verifying and validating your device. For electrosurgical devices, there is an FDA special controls guidance that defines the testing requirements and the content required for a 510k submission. Once you have developed a testing plan, confirm that the FDA agrees with your regulatory strategy and testing plan in a pre-submission meeting.

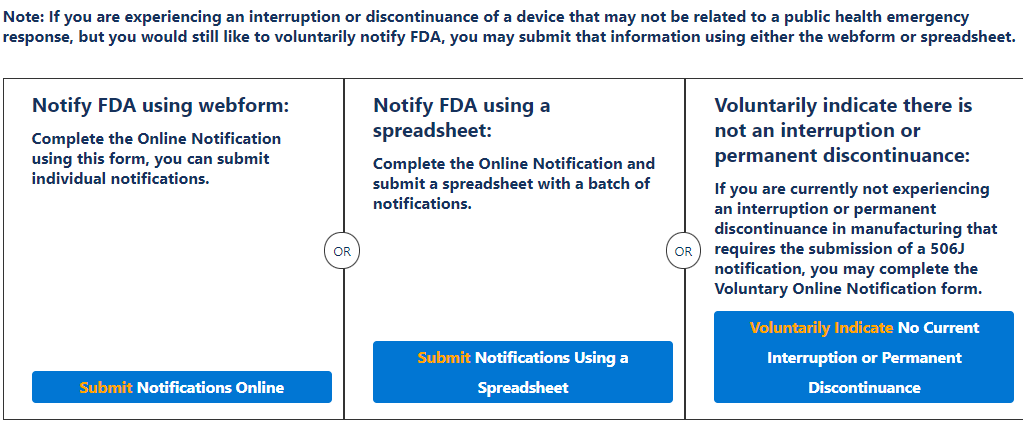

What type of 510k submission is required for your device?

There are three types of 510k submissions:

- Special 510k – 30-day review target timeline

- Abbreviated 510k – 90-day review target timeline (requires summary reports and use of recognized consensus standards)

- Traditional 510k – 90-day review target timeline

The special 510k pathway is intended for minor device modifications from the predicate device. However, this pathway is only eligible to your company if your company also submitted the predicate device. Originally, it was only permitted to submit a Special 510k for modifications that required the review of one functional area. However, the FDA recently completed a pilot study evaluating if more than one functional area could be reviewed. The FDA determined that up to three functional areas could be reviewed. However, the FDA determines whether they can complete the review within 30 days or if you need to convert your Special 510k submission to a Traditional submission. Therefore, you should also discuss the submission type with the FDA in a pre-submission meeting if you are unsure whether the device modifications will allow the FDA to complete the review in 30 days.

In 2019, the FDA updated the guidance document for Abbreviated 510k submissions. However, this pathway requires that the manufacturer use recognized consensus standards for the testing, and the manufacturer must provide a summary document for each test report. The theory is that abbreviated reports require less time for the FDA to review than full test reports. However, if you do not provide sufficient information in the summary document, the FDA will place your submission on hold and request additional information. This occurs in nearly 100% of abbreviated 510k submissions. Therefore, there is no clear benefit for manufacturers to take the time to write a summary for each report in the 510k submission. This also explains why less than 2% of submissions were abbreviated submission types in 2022.

The traditional type of 510k is the most common type of 510k submission used by manufacturers, and this is the type we recommend for all new device manufacturers.

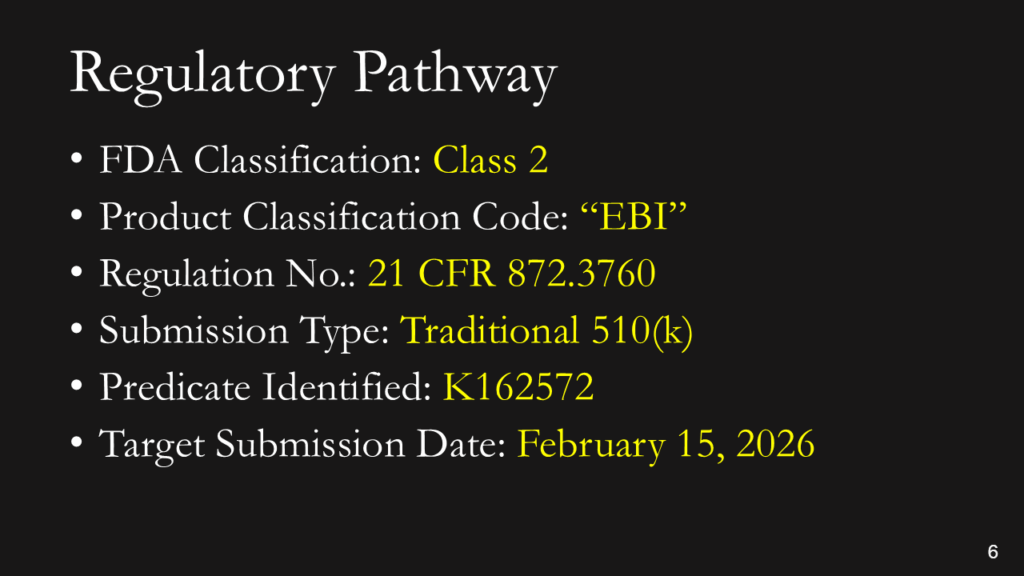

What is the regulatory pathway?

You don’t have to explain this. You could say, “This is a Class 2 device in the USA that requires a 510(k) submission. We have already identified a potential predicate, and we expect to submit our 510(k) in February.” If you don’t know the pathway this clearly, you should read our blog: https://medicaldeviceacademy.com/regulatory-pathway/. For most devices, we can answer this question in minutes. There are ~4,000 510(k) submissions each year, ~60 De Novo Submissions, and ~25 new PMAs (not including supplements). HDEs are even more rare. Therefore, if you plan to submit a De Novo application, you should already have a pre-submission or 513(g) classification request from the FDA to support it. Pre-subscriptions are always in the best interest of investors because they reduce the risk of having to repeat testing.

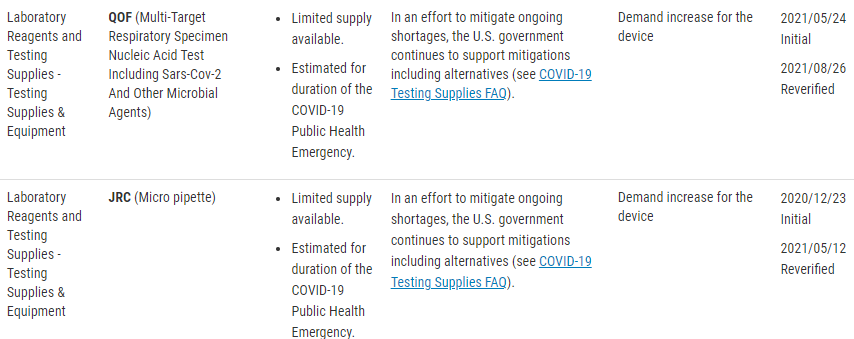

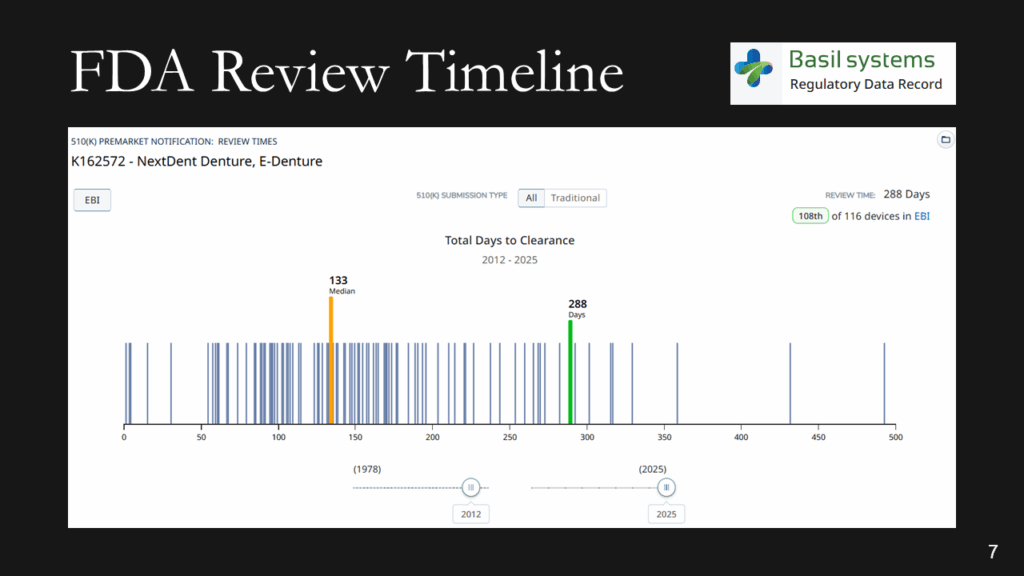

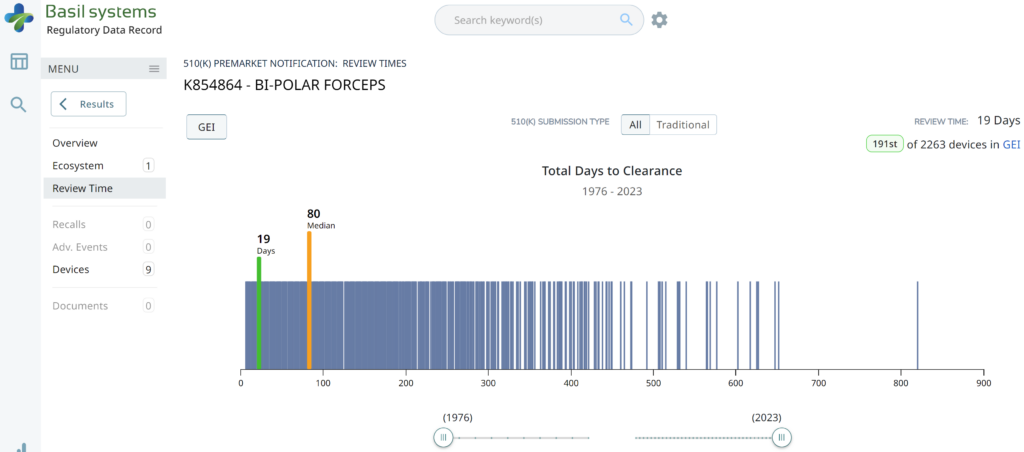

What is the expected FDA review timeline?

The FDA review timeline is variable. The target is 90 days for FDA review, but your submission can be placed on hold for various reasons. Therefore, historical data is the best indicator of the likely review timeline. The median review timeline is most likely. I only use data since 2012, as the RTA process, implemented in 2012, was a significant change to the FDA process. The eSTAR is a change in format, but it has made the process faster and more predictable. Basil Systems is the best tool for estimating the FDA review timeline and performing searches, but it’s only affordable for consultants who do this work daily and for large firms. The denture repair resin had 116 devices, but the example below for biopolar forceps has 2,263.

The two slides above in our MedTech investor pitch deck template are the only ones that specifically address the regulatory pathway. Another advantage of the Basil Systems software is that its database is lightning-fast, whereas the FDA database is a free government database (i.e., not quite as fast). Basil Systems also provides information that is hard to find in other places, such as the model number:

Wouldn’t having the model numbers for every device listed in the US FDA database be helpful?

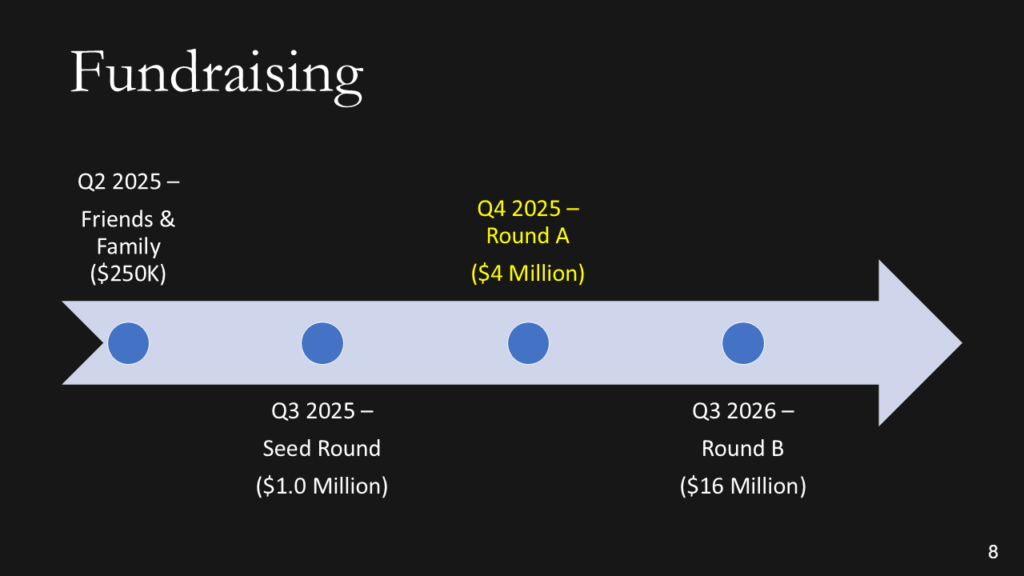

Fundraising efforts

Keep it simple. You aren’t sharing your CAP table, and if you aren’t confident when asking for money, nobody will give it to you.

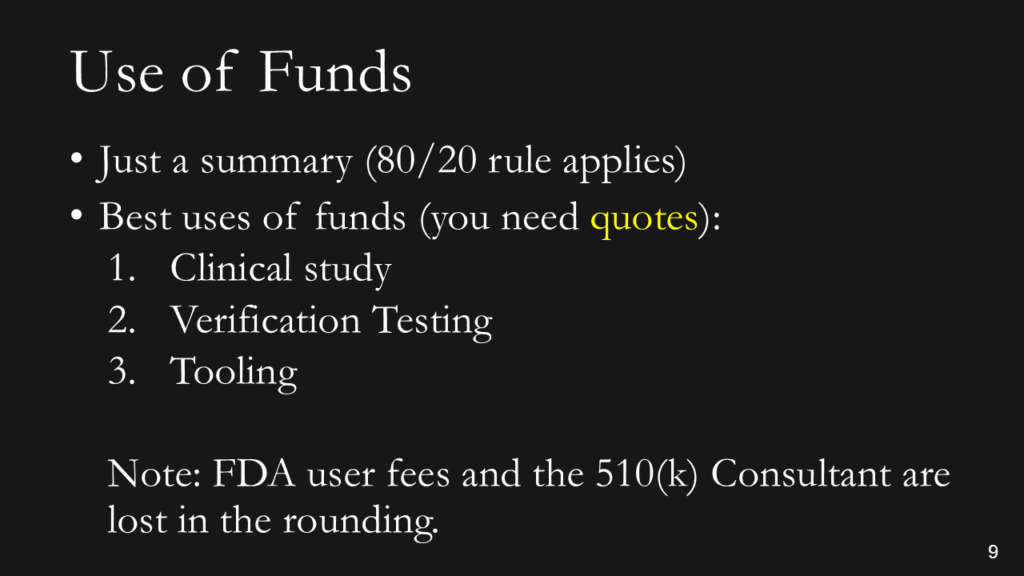

Use of funds

You need to explain where 80% of your money is going (not 100%). This is intended for potential investors, not an annual shareholder meeting or board meeting. You can always offer to answer more detailed questions after the presentation. To pay your salary is a horrible reason for using funds (suck it up and eat ramen), and to cover cash flow is the second-worst use of investor funds (that’s what loans are for). Sales, marketing, and developing sales channels are a good use of funds, but you have to be experienced in do this and have a specific plan you are prepared to defend. You also need to know who your potential suppliers will be, or you will not be prepared for fundraising. You need to have quotes in hand and be ready to spend that money.

Business model

Most companies present a 5-year P&L Projection in graph form, and they all look the same: “A Hockey Stick.” Nobody can accurately predict a P&L summary before they have a product that is ready to sell. Therefore, if you are raising Round A, please describe your business model in simple terms (i.e., cost of goods sold and pricing model). For market size, don’t tell us you have a billion-dollar market. Instead, be specific about number of customers and how many devices they use per year. That will make it REAL. For the market share %, you need to do better than…”if we just capture 1% of the market,” and 10% is not a conservative market share for a start-up. 1-10 units is conservative.

Contact us

Make it easy for people to contact you. You might not have your own YouTube channel, but you should have everything else on this page. No excuses!

Click on the button below for a copy of Medical Device Academy’s investor pitch deck template.

Regulatory pathway & MedTech investor pitch deck Read More »