Software Service Provider Qualification and Management

What is your company’s approach to qualifying a software service provider and managing software-as-a-service (SaaS) for cybersecurity?

The need for qualifying and managing your software service provider

Most of the productivity gains of the past decade are related to the integration of software tools into our business processes. In the past, software licenses were a small part of corporate budgets, and the most critical software tools helped to manage material requirements planning (MRP) functions and customer relationship management (CRM). Today, there are software applications to automate every business process. Failure of a single software service provider, also known as “Software-as-a-Service” or (Saas), can paralyze your entire business. In the past, business continuity plans focused on labor, power, inventory, records, and logistics. Today our business continuity plans also need to expand for the inclusion of software service providers, internet bandwidth, websites, email, and cybersecurity. This new paradigm is not specific to the medical device industry. The medical device industry has become more dependent upon its supply chain due to the ubiquity of outsourcing, and what happens to other industries will eventually filter its way into this little collective niche we share. With that in mind, how do we qualify and manage a software service provider?

Threats to software service providers (Kaseya Case Study)

Two years ago the WannaCry ransomware attack affected 200,000 computers, 150 countries, and more than 80 hospitals.

Kaseya isn’t a hospital. Kaseya is a software service provider company. So why is this example relevant to the medical device industry?

The ransomware attack on Kaseya was severe enough that both CISA and the FBI got involved, and it compromised some Managed Service Providers (MSPs) and downstream customers. This supply chain ransomware attack even has its own Wikipedia page. The attack prompted Kaseya to shut down servers temporarily. None of this is a critique of Kaseya or their actions. They were merely the latest high-profile victim of a cyberattack in the news. Now cybercriminals are attacking your supply chain. We want to emphasize the concepts and considerations of this type of attack as it pertains to your business.

What supplier controls do you require for a software service provider?

If you are a manufacturer selling a medical device under the jurisdiction of the U.S. FDA, you need to comply with 21 CFR 820.50 (i.e. purchasing controls). The FDA requires an established and maintained procedure to control how you are ensuring what your company buys meets the specified requirements of what you need. Many device manufacturers only consider suppliers that are making physical components, but a software service provider may be critical to your device if your device is software as a medical device (SaMD), includes software, or interacts with a software accessory. A software service provider may also be involved with quality system software, clinical data management, or your medical device files. Do you purchase software-as-a-service or rely upon an MSP for cloud storage?

You need to determine if your software service provider is involved in document review or approval, controlling quality records, Protected Health Information (PHI), or electronic signature requirements. You don’t need a supplier quality agreement for all of the off-the-shelf items your company purchases. For example, it would be silly to have Sharpie sign a supplier quality agreement because you occasionally purchase a package of highlighters. On the other hand, if you are relying upon Docusign to manage 100% of your signed quality records, you need to know when Docusign updates its software or has a security breach. You should also be validating Docusign as a software tool, and there should be a backup of your information.

21 CFR 820.50 requires that you document supplier evaluations to meet specified and quality requirements per your “established and maintained” procedure. The specified requirements for this supplier might include the following:

- How much data storage do you need?

- How many user accounts do you need?

- Do you need unique electronic IDs for each user?

- Do you need tech support for the software service?

- Is the software accessed with an internet browser, is the software application-based, or both?

- How much does this software service cost?

- Is the license a one-time purchase? Or is it a subscription?

The quality requirements for a supplier like this may look more like these questions;

- How is my information backed up?

- Can I restore previous file revisions in the case of corruption?

- How can I control access to my information?

- Can I sign electronic documents? If yes, is it 21 CFR Part 11 compliant?

- Does this supplier have downstream access to my information? (can the supplier’s suppliers see my stuff?)

- Do I manage PHI? If so, can this system be made HIPAA compliant? What about HITECH?

- What cybersecurity practices does this supplier utilize?

- How are routine patches and updates communicated to me?

A risk-based approach to supplier quality management

ISO 13485:2016 requires that you apply a risk-based approach to all processes, including supplier quality management. A risk-based approach should be applied to suppliers providing both goods and services. For example, you may order shipping boxes and contract sterilization services. Both companies are suppliers, but in this example, the services provided by the contract sterilizer are associated with a much higher risk than the shipping box supplier. Therefore, it makes sense that you would need to exercise greater control over the sterilizer. Software service providers are much like contract sterilizers. SaaS is not tangible but the service provided may have a high level of risk and potential impact on your quality management system. Therefore, you need to determine the risk associated with SaaS before you can evaluate, control, and monitor a software service supplier.

First, you need to document the qualification of a new supplier. It would be nice if your cloud service provider had a valid ISO 13485:2016 certification. You would then have an objectively demonstratable record of their process controls and know that they are routinely audited to maintain that certification. They would also understand and expect to undergo 2nd party supplier audits because they operate in the medical device industry. Alternatively, a software service provider may have an ISO 9001:2015 certification. This is a general quality system certification that may be applied to all products or services. In the absence of quality system certification, you can audit a potential supplier. For some suppliers, this makes sense. However, many companies that are outside of the medical device industry do not even have a quality system because it is not required or typical of their industry. For the ones that do, though, you can likely leverage their existing certifications and accreditations.

Cybersecurity standards you should know

Most cloud service providers will not have ISO 13485 certification, because it is a quality management standard specific to the medical device industry. However, you might look for some combination of the following ISO standards that may be relevant to a software service provider:

- ISO/IEC 27001 Information Technology – Security Techniques – Information Security Management Systems – Requirements

- ISO/IEC 27002:2013 Information Technology. Security Techniques. Code Of Practice For Information Security Controls

- ISO/IEC 27017:2015 Information Technology. Security Techniques. Code Of Practice For Information Security Controls Based On ISO/IEC 27002 For Cloud Services

- ISO/IEC 27018:2019 Information Technology – Security Techniques – Code Of Practice For Protection Of Personally Identifiable Information (PII) In Public Clouds Acting As PII Processors

- ISO 22301:2019 Security And Resilience – Business Continuity Management Systems – Requirements

- ISO/IEC 27701:2019 Security Techniques. Extension to ISO/IEC 27001 and ISO/IEC 27002 For Privacy Information Management. Requirements And Guidelines

Does your software service provider have SOC reports?

The acronym “SOC” stands for Service Organization Control, and these reports were established by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. SOC reports are internal controls that an organization utilizes and each report is for a specific subject. SOC reports apply to varying degrees for SaaS and MSP Suppliers

The SOC 1 Report focuses on Internal Controls over Financial Reporting. Depending on what information you need to store on the cloud, this report could be more applicable to the continuity of your overall business than specifically to your quality management system.

The SOC 2 Report addresses what level of control an organization places on the five Trust Service Criteria: 1) Security, 2) Availability, 3) Processing Integrity, 4) Confidentiality, and 5) Privacy. As a medical device manufacturer, these areas would touch on control of documents, control of records, and process validation, among other areas of your quality system. Some suppliers may not share a SOC 2 report with you, because of the amount of confidential detail provided in the report.

The SOC 3 Report will contain much of the same information that the SOC 2 Report contains. They both address the five Trust Service Criteria. The difference is the intended audiences of the reports. The SOC 3 is a general use report expected to be shared with others or publicly available. Therefore, it doesn’t go into the same intimate level of detail as the SOC 2 report. Specifically, information regarding what controls a system utilizes is very brief if identified at all compared to the description and itemized list of controls in the SOC 2 Report.

Other ways to qualify and manage your software service provider

SOC reports will help paint a picture of the organization you are trying to qualify for. You will also need to evaluate the supplier on an ongoing basis. It is essential to know if the supplier is subject to routine audits and inspections to maintain applicable certifications and accreditations. For example, if their ISO certificate lasts for three years, you should know that you should follow up with your supplier for their new certificate at least every three years. On the other hand, if they lose certification, it may signify that the supplier can’t meet your needs any longer and you should find a new supplier.

There is a long list of standards, certifications, accreditations, attestations, and registries that you can use to help qualify a SaaS or MSP supplier. One such registry is maintained by Cloud Security Alliance (i.e. the CSA STAR registry). “STAR” is an acronym standing for Security, Trust, Assurance, and Risk. CSA describes the STAR registry in their own words:

“STAR encompasses the key principles of transparency, rigorous auditing, and harmonization of standards outlined in the Cloud Controls Matrix (CCM) and CAIQ. Publishing to the registry allows organizations to show current and potential customers their security and compliance posture, including the regulations, standards, and frameworks they adhere to. It ultimately reduces complexity and helps alleviate the need to fill out multiple customer questionnaires.”

Some of the questions your supplier qualification process should be asking about your SaaS and MSP suppliers include:

- Why do I need this software service?

- Which standards, regulations, or process controls need to be met?

- What is required for qualifying suppliers providing SaaS or an MSP?

- How will you monitor a software service provider?

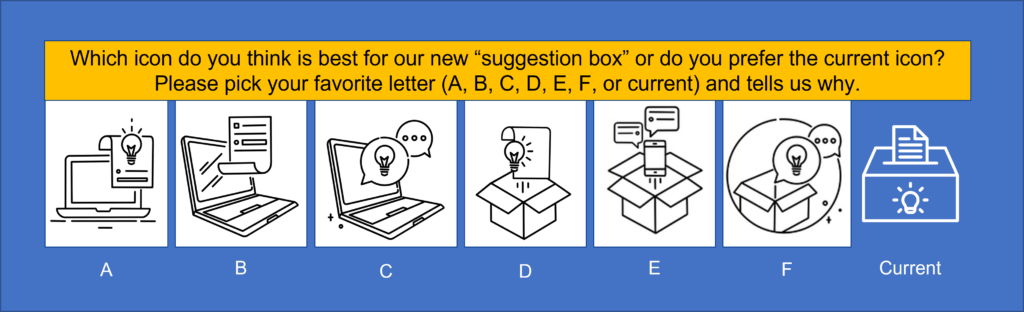

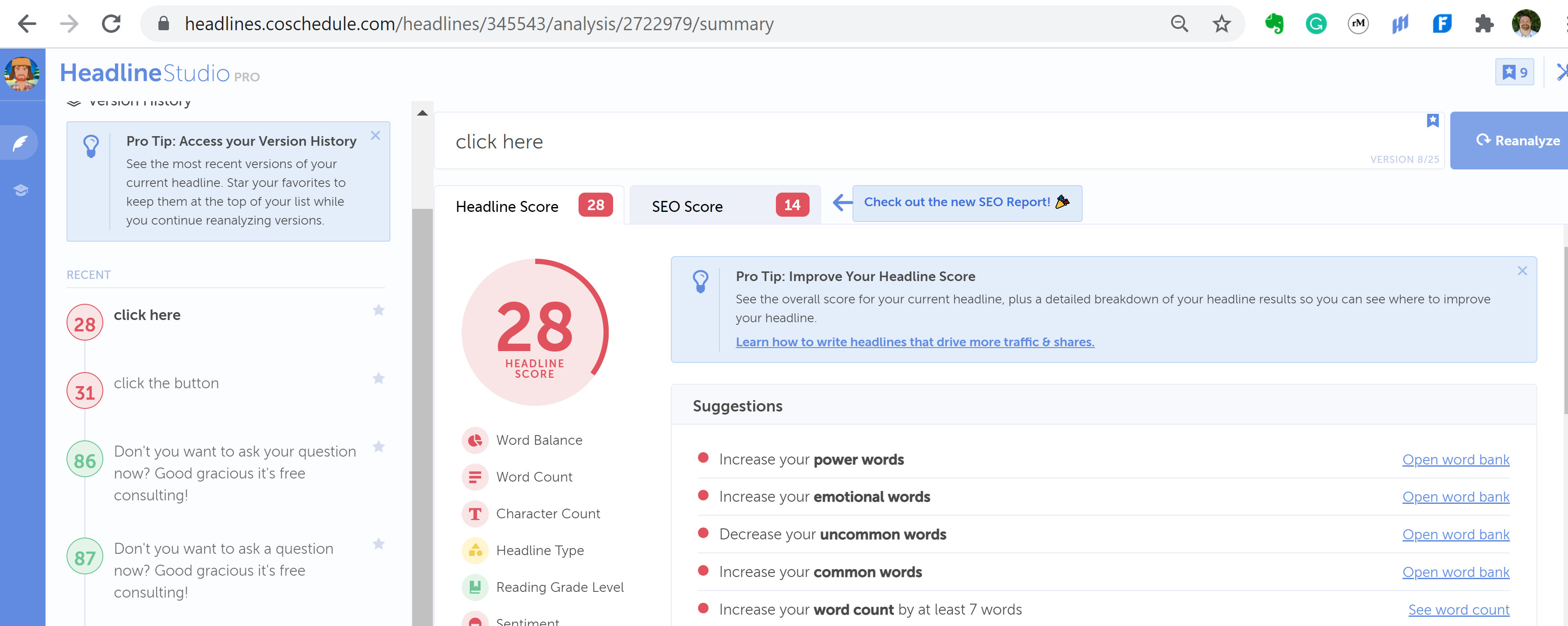

ISO certification, SOC reports, and the CSA STAR registry are supplier evaluation tools you can use for supplier qualification and monitoring. When you use these tools, make sure that you ask open-ended questions instead of close-ended questions. Our webinar on supplier qualification provides several examples of how to convert your “antique” yes/no questions into value-added questions.

Your software service provider should be able to provide records and metrics demonstrating the effectiveness of their cybersecurity plans. Below are three examples of other types of records you might request:

- Cloud Computing Compliance Controls Catalogue or “C5 Attestation Report”

- System Security Plan for Controlled Unclassified Information in accordance with NIST publication SP 800-171

- Privacy Shield Certification to EU-U.S. Privacy Shield or Swiss-U.S. Privacy Shield

The privacy shield certification may be especially important for companies with CE Marked devices in order to comply with the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or Regulation 2016/679.

A final consideration for supplier qualification is, “Who are the upstream suppliers?” It is essential to know if your new supplier or their suppliers will have access to Protected Health Information (PHI). Since you have less control of your supplier’s subcontractors, you may need to evaluate how your supplier manages their supply chain and which general cybersecurity practices your supplier’s subcontractors adhere to.

Additional cybersecurity, software validation, and supplier quality resources

For more resources on cybersecurity, software validation, and supplier quality management please check out the following resources:

- Live Cybersecurity webinar – August 19

Software Service Provider Qualification and Management Read More »