Three (3) important technical file and 510k submission differences

This article explains the three (3) critical technical file and 510k submission differences: 1) risk, 2) CER, and 3) PMCF.

There are many differences between a technical file and a 510k submission, including the fact that technical files are audited annually while a 510k submission is reviewed only once. ISO 14971 requires a risk management file, whether you are selling a medical device in the EU or the USA, but the US FDA doesn’t require that you submit a risk management file as part of the 510k submission. If you design and develop a medical device with software, you must submit a risk analysis if the software has a moderate level of concern or higher. However, risk analysis is only a small portion of a risk management file.

Only 10-15% of 510k submissions require clinical studies, but 100% of medical devices with CE Marking require a clinical evaluation report (CER) as an essential requirement in the technical file. The clinical evaluation report (CER) is an essential requirement (ER) 6a in Annex I of the Medical Device Directive (MDD). Even class 1 devices that are non-sterile and have no measuring function require a clinical evaluation report (CER). Yes, even adhesive tape with a CE Mark requires a clinical evaluation report in the technical file.

Annex X, 1.1c of the Medical Device Directive (MDD), requires that medical device manufacturers perform a post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) study or provide a justification for not conducting a post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) study. In the past, companies attempted to claim that their device is equivalent to other medical devices, and therefore a post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) study is not required. However, in January 2012, a guidance document (MEDDEV 2.12/2) was published to provide guidance regarding when a PMCF study needs to be conducted. This guidance makes it clear that PMCF studies are required for many devices–regardless of equivalence to other devices already on the market.

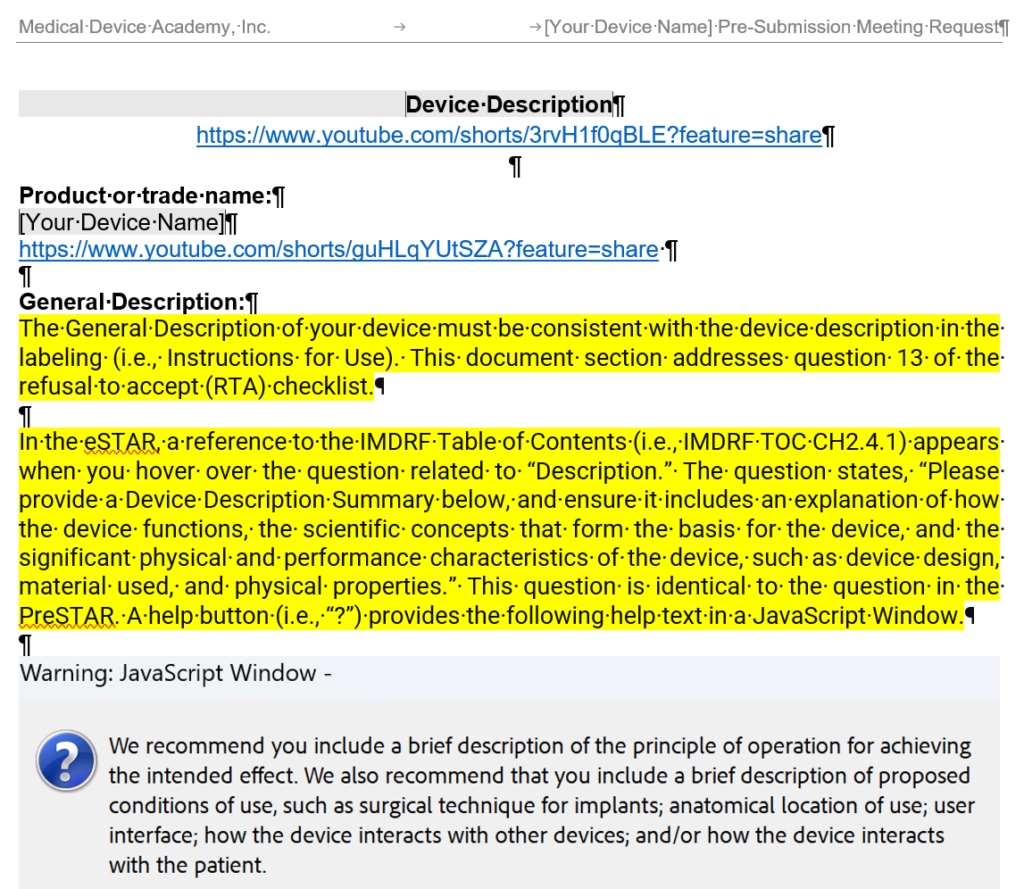

Risk management file for technical file and 510k submission

The FDA only requires documentation of risk management in a 510k submission if the product contains software, and the risk is at least a “moderate concern.” Even though you are required to perform a risk analysis, a knee implant would not require submission of the risk analysis with the 510k. If a product is already 510k cleared, you may be surprised to receive audit nonconformities related to your risk management documentation for CE Marking. The most common deficiencies with a risk management file are:

- compliant with ISO 14971:2007 instead of EN ISO 14971:2012

- reduction of risks as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP) instead of reducing risks as far as possible (AFAP)

- reducing risks by notifying users and patients of residual risks in the IFU

- only addressing unacceptable risks with risk controls instead of all risks–including negligible risks

If you are looking for a risk management procedure, please click here. You might also be interested in my previous blog about preparing a risk management file.

Clinical evaluation report (CER) for technical file and 510k submission

The FDA does not require a clinical evaluation report (CER), and up until 2010, only some CE Marked products were required to provide a clinical evaluation report (CER). In 2010 the Medical Device Directive (MDD) was revised, and now a clinical evaluation report (CER) is a general requirement for all medical devices (i.e., Essential Requirement 6a). This requirement can be met by performing a clinical study or by performing a literature review. Since 510k devices only require a clinical study 10-15% of the time, it is unusual for European Class 1, Class IIa, and Class IIb devices to have clinical studies. This also means that very few clinical studies are identified in literature reviews of these low and medium-risk devices.

The most common problem with the clinical evaluation reports (CERs) is that the manufacturer did not use a pre-approved protocol for the literature search. Other common issues include an absence of documented qualifications for the person performing the clinical evaluation and failure to include a copy of the articles reviewed in the clinical evaluation report (CER). These requirements are outlined in MEDDEV 2.7/1, but the amount of work required to perform a clinical evaluation that meets these requirements can take 80 hours to complete.

If you are looking for a procedure and literature search protocol for preparing a clinical evaluation report (CER), please click here. You might also be interested in my previous blog about preparing a clinical evaluation report (CER).

Post-Market Surveillance (PMS) & Post-Market Clinical Follow-up (PMCF) Studies for technical file and 510k submission

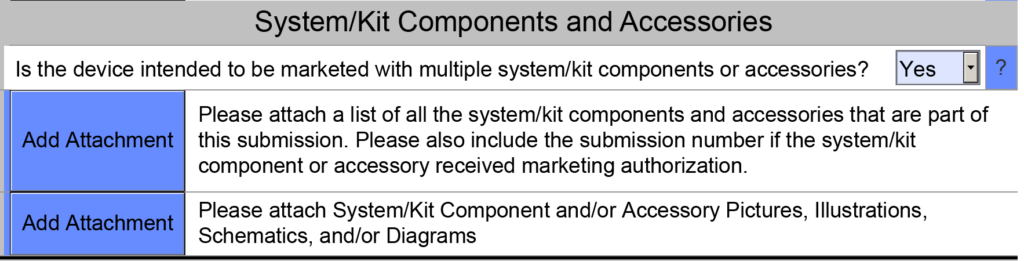

Post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) is only required for the highest risk devices by the FDA. For CE Marking, however, all product families are required to have evidence of post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) studies or a justification for why post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) is not required. The biggest mistake I see is that manufacturers refer to their post-market surveillance (PMS) procedure as the post-market surveillance (PMS) plan for their product family, and they say that they do not need to perform a post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) study because the device is substantially equivalent to several other devices on the market.

Manufacturers need to have post-market surveillance (PMS) plan that is specific to a product or family of products. The post-market surveillance (PMS) procedure needs to be updated to identify the frequency and product-specific nature of post-market surveillance (PMS) for each product family or a separate document that needs to be created for each product family. For devices that are high-risk, implantable, or devices that have innovative characteristics, the manufacturer will need to perform some post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) studies. Even products with clinical studies might require post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) because the clinical studies may not cover changes to the device, accessories, and range of sizes. MEDDEV 2.12/2 provides guidance on the requirements for post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) studies. Still, most companies manufacturing moderate-risk devices do not have experience obtaining patient consent to access medical records to collect post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) data–such as postoperative imaging.

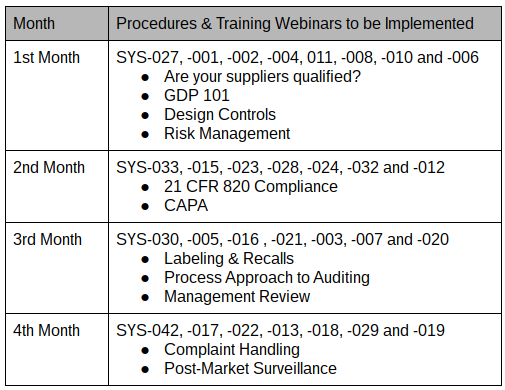

Procedures & Webinars

If you are looking for a procedure for post-market surveillance (PMS), please click here. If you are interested in learning more about post-market surveillance and post-market clinical follow-up (PMCF) studies, we also have a webinar on this topic.

Three (3) important technical file and 510k submission differences Read More »