Audit Findings – How to communicate good and bad findings.

This blog describes best practices for communicating audit findings during an audit, in the closing meeting, and in the audit report.

Would you like to be surprised by an auditor with a major nonconformity? Of course not! Nobody likes that kind of surprise. However, do you know how to effectively communicate your audit findings during the audit, in the closing meeting, and in your audit report?

Audit findings should be communicated at the time the objective evidence is gathered, and it should be clearly stated whether you think the finding is a nonconformity or an opportunity for improvement. Give the auditee an opportunity to correct you.

Audit Finding Example

If you are auditing the process for creating a medical device file, and you are unable to find evidence of product specifications (i.e., ISO 13485:2016, Clause 4.2.3b), then you should restate the requirement and explain why this is a nonconformity. It may be a nonconformity because that requirement is not included in the procedure or index for your medical device file. It may be a nonconformity because the product specification is obsolete and needs to be updated. It may be a nonconformity because you were unable to find the product specification anywhere in the device master record (DMR) index or technical file index. You might also be surprised to learn that product specifications are included in the product user manual, but the process owner forgot that because they were very nervous. The morning after the audit, the process owner may be prepared to show you exactly what you were looking for, including procedural requirements and training.

How do you respond when findings are resolved

Some auditors are irritated when they spend time following the audit trail, and after they have taken the time to write a nonconformity, the auditee finally produces the evidence requested. Some auditors say, “It’s too late. You were unable to provide the record when it was requested.” That’s not a value-added finding. The right approach is to say, “Excellent! Now we don’t need to issue a nonconformity or investigate the root cause for a missing product specification.” You might also add, “As a follow-up to this audit, consider ways you can make the product specifications and other required technical documentation easier to find during an audit.” If a similar scenario is repeated during the audit, you might consider writing an OFI beginning with the word “Consider.” However, be careful of suggesting solutions. Medical Device Academy adds cross-references to requirements in each procedure, but that is time-consuming and not required.

How to grade an audit finding

In our example above, if evidence of the product specification was not found, that would be a nonconformity. If several other requirements in the medical device file were not available, it would still be a nonconformity. Some people would grade a single lapse as a “minor,” but if multiple requirements are missing they would grade the finding as a “major.” This is not enough to deserve the grading of a “major” but grading subjectivity is difficult to avoid. The specification might exist, but it was accidentally omitted from the file. The specification might not be documented for the file sampled, but it may be easily identified for other product files. The specification might only be missing, because a new employee forgot it and the file was not thoroughly reviewed yet. Therefore, the auditor should consider the missing element an “audit trail.” They should review previous audit reports for similar nonconformities, sample additional requirements, sample other files, and review training records before determining the grading.

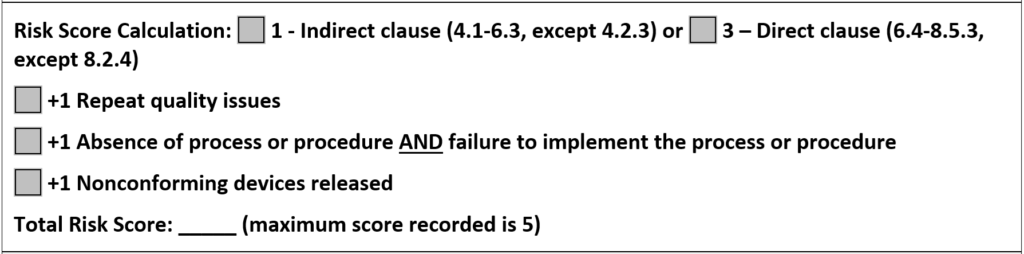

Why do the GHTF and MDSAP guidance documents use quantitative grades?

In 2012, the Global Harmonization Task Force (GHTF) published a guidance document for grading auditing findings. That guidance proposed a quantitative scoring system with a range of 1-5. Initially, I thought this system was overly complicated. Later, the Medical Device Single Audit Program (MDSAP) adopted the same quantitative scoring system. Since many of our clients adopted MDSAP, we had to learn the MDSAP audit approach and we had to learn how to grade audit findings quantitatively. After using the new system, I realized that the quantitative approach was faster because the objective grading reduced the time required to make a decision on the grade of the finding.

Direct and indirect impact on product safety and performance

Experienced auditors have most of ISO 13485 memorized, and they usually know which requirements are included in Clauses 4.1-6.3, and which requirements are found later in the standard. Therefore, identifying whether the finding is “direct” or “indirect” is easy. Clauses 4.1-6.3 are indirect clauses, with the exception of 4.2.3 which is direct. There is also one exception to the direct clauses; Clause 8.2.4 is the only clause within Clauses 6.4-8.5.3 that is indirect. It would be easy to persuade someone that there should be additional exceptions, but it would just make the process slower and subjective. Using the clause number for each requirement to determine the initial scoring makes the process faster and more reliable.

When do escalation rules apply?

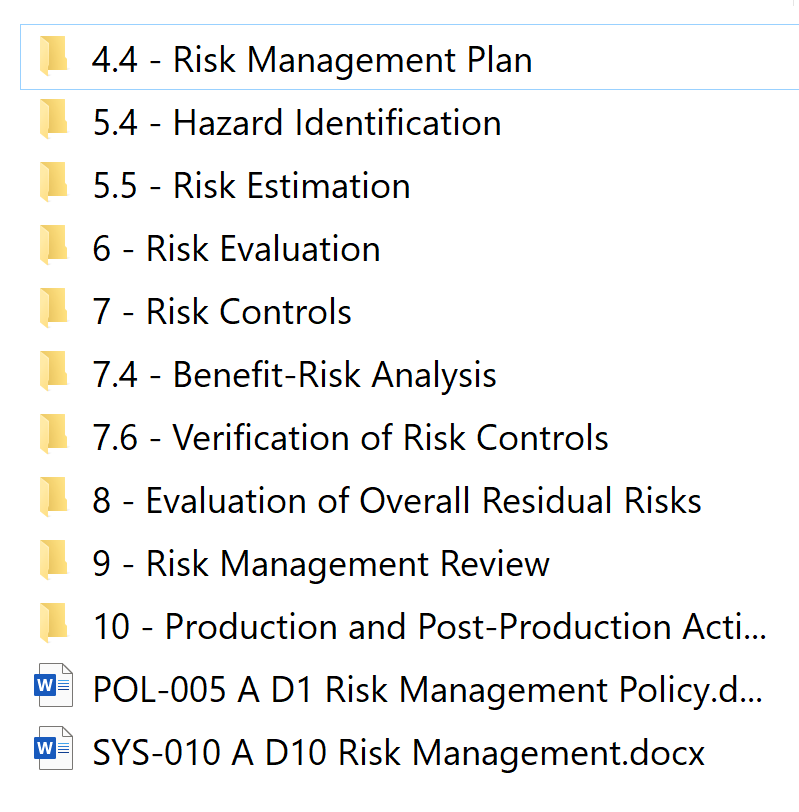

There are three escalation rules to consider when grading a nonconformity in the GHTF or MDSAP audit approach. The image below is included in our CAPA form to help remind people of the scoring. The first rule is specific to a repeat nonconformity in the past three (3) years. The second escalation rule is controversial because many people believe the absence of a procedure or records should be sufficient by itself to escalate a finding. However, it’s just a grade, and if the finding is escalated, we want there to be no doubt that the process is not able to meet the requirements. The final escalation rule is the most serious because shipping nonconforming products requires implementation of a recall or field service corrective action (FSCA). Medical Device Academy applies these same three escalation rules when deciding whether a finding is a “major” if a client does not use the MDSAP audit scoring system. This ensures that our grading is objective and it is based on international guidance. We use this same scoring system for internal auditing, supplier auditing, and CAPAs.

Audit findings must include more than nonconformities

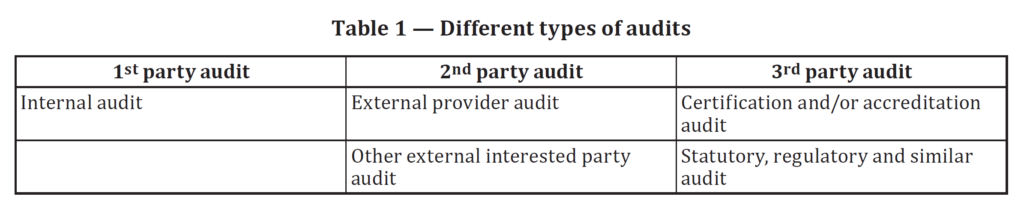

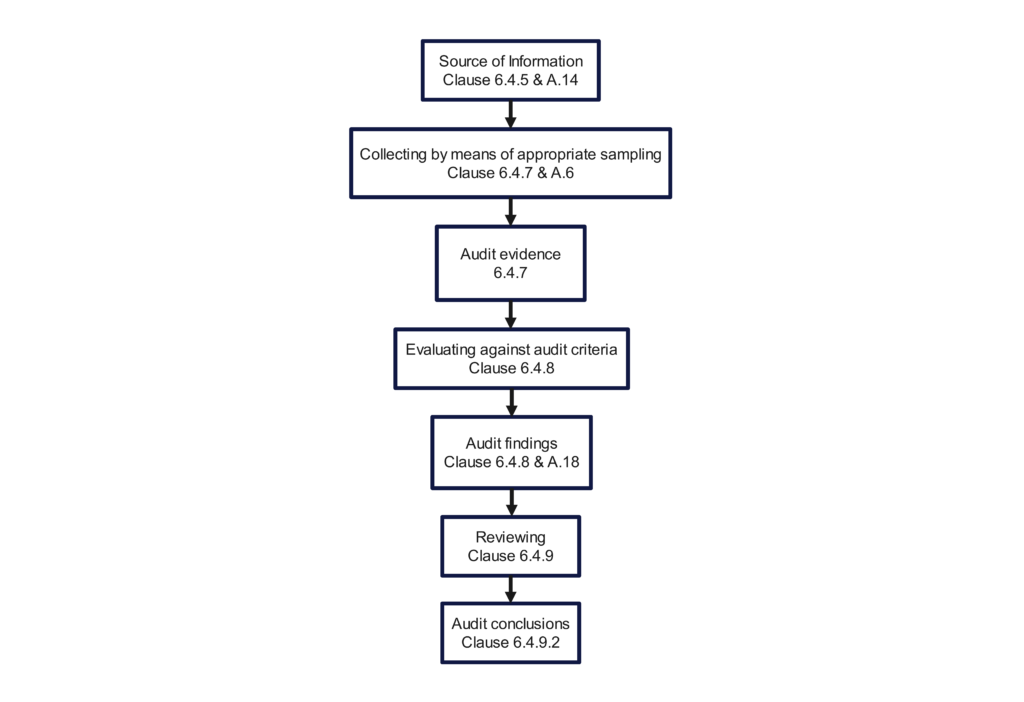

In the paragraphs above, we discussed the grading of nonconformities; however, reporting audit findings involves more than just grading nonconformities. ISO 19011:2011 is the official guidance document for auditors of Quality Management Systems, and ISO 13485 is the quality system standard for medical device manufacturers. Section 6.4.2 of this Standard explains best practices for an opening meeting.

- Method of reporting audit findings, including grading, if any

- Conditions under which the audit may be terminated

- Time and place of the closing meeting

- How to deal with possible findings during the audit

- System for feedback from the auditee on findings or conclusions of the audit

- Process for complaints and appeals

The opening meeting is the ideal opportunity to outline how you and your team will present audit findings and to clarify that you will discuss both the strengths and weaknesses of the quality system verbally in the closing meeting and in the audit report. If the auditee is new to auditing, you might even explain the three-part structure of how nonconformities are written.

Conditions for Termination

The option to terminate an audit is typically reserved for a certification audit where multiple major nonconformities are identified, and there is no point in continuing. Termination is highly discouraged because it is better to be aware of all minor and major nonconformities immediately, rather than waiting until the certification audit is rescheduled. The certification body will charge you for their time anyway.

Another reason for termination is when an auditor acts unreasonably or inappropriately. This is rare, but it happens. If the audit is terminated, you should communicate this to upper management at both the certification body and the company, regardless of which side of the table you sit on. For FDA inspections, this is not an option. For audits performed by Notified Bodies, there is the possibility of suspension of a certificate in response to audit termination. Therefore, I always recommend appealing after the fact, instead of termination. Appealing also works for FDA inspections.

Closing Meeting

The closing meeting should be conducted as scheduled, and the time/location should be communicated to upper management in the audit agenda and during the opening meeting. Top management won’t be happy about nonconformities, but failure to communicate when the closing meeting will be conducted will irritate them further. You should also ensure that a teleconference invitation is set up in advance for the closing meeting, allowing top management to participate remotely if necessary.

At the closing meeting, the auditee should never be taken by surprise. If an issue remains unfulfilled at the closing meeting, the auditee should expect a minor nonconformity—unless the issue warrants a major nonconformity. Since a minor nonconformity can result from a single lapse in fulfilling a requirement, it is challenging for an auditee to argue that an issue does not warrant a minor nonconformity. Typically, the argument is that you are not consistent with other auditors. The most common response to that issue is, “Audits are just a sample, and previous auditors may not have seen the same objective evidence.” The more likely scenario, however, is that the previous auditor interprets the requirements, rather than reviewing them with the client and ensuring both parties agree before a finding is issued.

If a finding is major, the auditee should have very few questions. Additionally, I often find that the reason for a major nonconformity is a lack of management commitment to address the root cause of the problem. Issuing a major nonconformity is sometimes necessary to get management’s attention.

Regardless of the grading, all audit findings will require a corrective action plan—even an FDA warning letter requires a CAPA plan. Therefore, a major nonconformity is not a disaster. You just need to create a more urgent plan for action.

How to deal with audit findings

All guides and auditees should be informed of potential findings at the time an issue is identified. This is important so that an auditee has the opportunity to clarify the evidence being presented. Often, nonconformities result from miscommunication between the auditor and the auditee. This often occurs when the auditor lacks a thorough understanding of the process being audited. It is a tremendous waste of time for both sides when this occurs. If there is an actual nonconformity, it is also important to gather as much objective evidence as possible for the auditor to write a thorough finding and for the auditee to prepare an appropriate corrective action plan in response to the discovery.

Feedback from the Auditee

As an auditor, I encourage auditees to provide honest feedback directly to me and to management, so that I can continue to improve. If you are providing feedback about an internal auditor or a supplier auditor, you should always give feedback directly to the person before going to their superior. You are both likely to work together in the future, and you should give the person every opportunity to hear the feedback firsthand.

When providing feedback from a third-party certification audit, you should know that there will be no negative repercussions against your company if you complain directly to the certification body. At most, the certification body will assign a new auditor for future audits and investigate the need for taking action against the auditor. In all likelihood, any action taken will be “retraining.” I never fired somebody for a single incident—unless they broke the law or did something unsafe. The key to providing feedback, however, is to be objective. Give specific examples in your complaint, and avoid personal feelings and opinions.

Complaints and appeals of audit findings

As an auditor, one of the most important (and difficult) things to learn is how to issue a nonconformity—especially a major. This is typically done at the closing meeting of an audit; however, the closing meeting is not where the process of issuing the nonconformity begins. Issuing a nonconformity starts in the opening meeting.

As the auditee, you should ask for the contact information of the certification body during the opening meeting. Ask with a smile—just in case you disagree, and so you can provide feedback (which might be positive). As the auditor, you should always provide the certification body’s contact information (if they are a third-party auditor). If you are conducting a supplier audit or an internal audit, you probably know the auditor’s boss, and there is perhaps no formal complaint or appeals process. In the case of a supplier audit, the customer is always right—even when they are wrong.

Additional Auditor Training

If you would like to learn more about auditing methods and best practices, consider registering for our Lead Auditor Training Course.

Audit Findings – How to communicate good and bad findings. Read More »