Smile, because you should never be scared of a surprise FDA inspector

If you have a surprise FDA inspector visit, you should never be scared because there is no difference between the best and worst-case outcome.

Why are you scared of an FDA inspector?

There are a number of reasons why you might be scared of an FDA inspector, but if you keep reading you will learn why 95% of your fear is self-induced. A small percentage of device manufacturers evaluate the performance of quality managers based on the outcome of FDA inspections, but you have no control over whom the FDA Office of Regulatory Affairs (ORA) assigns to perform your inspection. If your company belongs to this 5% minority, you need to change top management’s approach to regulators or you need to find a new employer. For the majority of us, we are scared of embarrassment, failure, or being “shut down.”

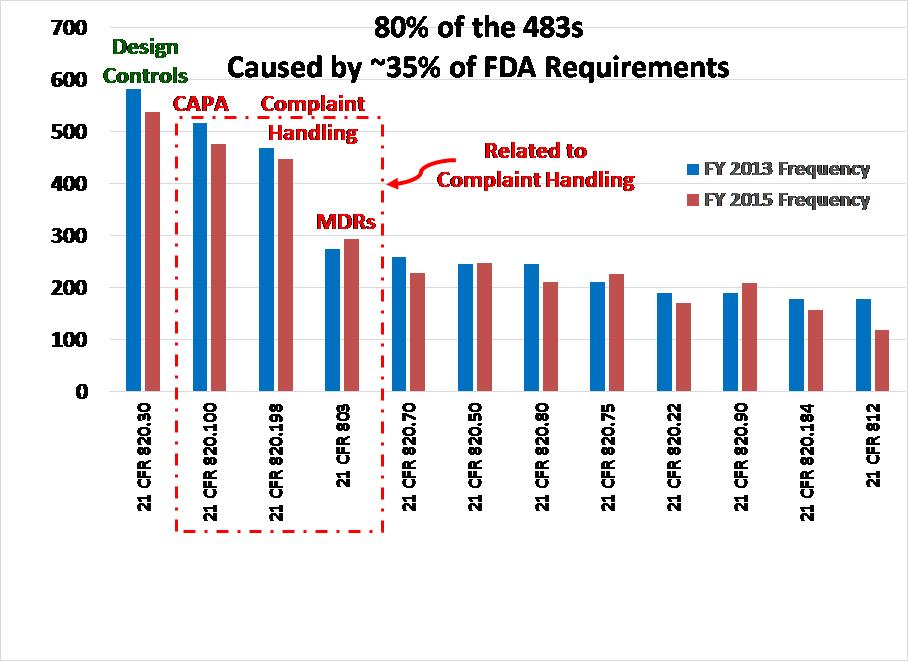

There are rare examples of where the FDA has taken action to stop the distribution of medical devices, but this is only done as a last resort. Usually, companies cooperate with the FDA with the hope of being able to resolve quality issues and resume distribution after corrective actions are implemented. Not only is this type of action rare, but there will be a prior visit to your facility and prior written communication from ORA before you receive a warning letter–let alone removal of your company’s device(s) from the market. You can’t pass or fail an FDA inspection. The FDA inspector is verifying compliance with the FDA Quality System Regulation (i.e. 21 CFR 820) as well as the requirements for medical device reporting (i.e. 21 CFR 803), reports of corrections and removals (i.e. 21 CFR 806), investigational device exemptions (i.e. 21 CFR 812), and unique device identification (UDI). FDA inspectors only have time to sample your records, and with any sampling plan, there is always uncertainty. When you do receive an FDA 483 inspection observation you should not consider it to be a condemnation of your company. Likewise, an absence of 483 observations is not a reason to celebrate.

Why you should not be embarrassed when you receive a 483 from an FDA inspector

The most irrational response to an FDA 483 inspection observation is embarrassment. Our firm specializes in helping start-up medical device companies get their first product to market. This includes providing training and helping them to implement a quality system. When our clients have their first FDA inspection, it is not uncommon to receive an FDA Form 483 inspection observation. Start-ups have limited resources and limited experience, and most of the employees have never participated in an FDA inspection before. Experience matters and immature quality systems have only a limited number of records to sample. Any mistakes are easy for an inspector to find.

Instead of feeling embarrassed, acknowledge and embrace your inexperience. For example, during the opening meeting with an FDA inspector, you might say, “We are a new company, and this is our first FDA inspection. I am also a first-time quality manager. If you find anything that we are doing incorrectly, please let us know and we will make immediate corrections and start working on our CAPA plan.” You can say this with a smile :), and you can genuinely mean what you said because it’s true.

Anticipation is always worse than reality

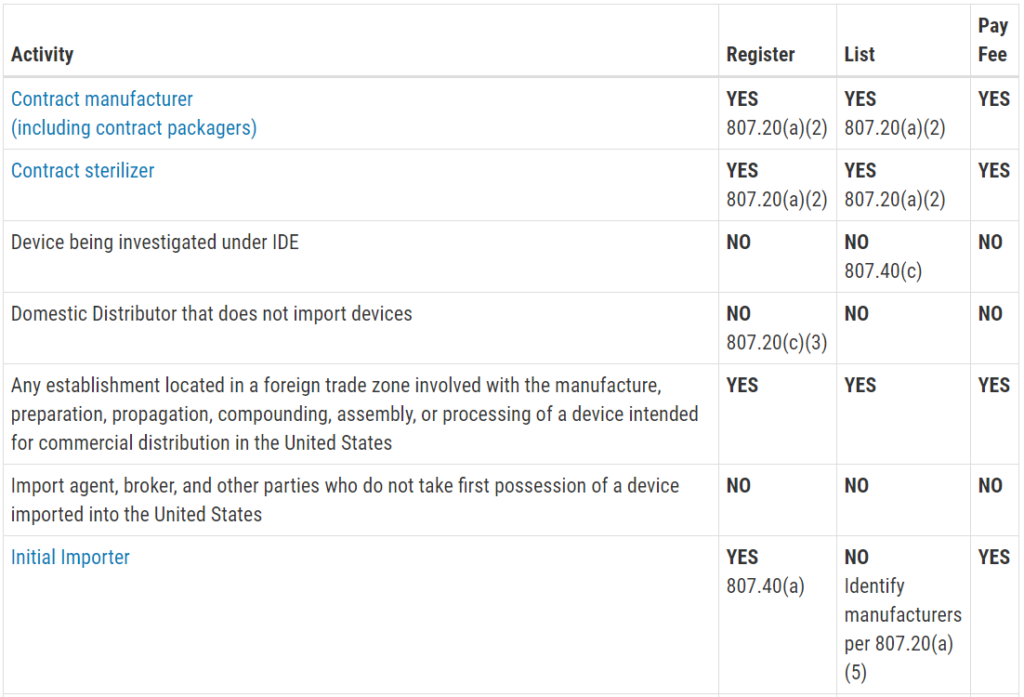

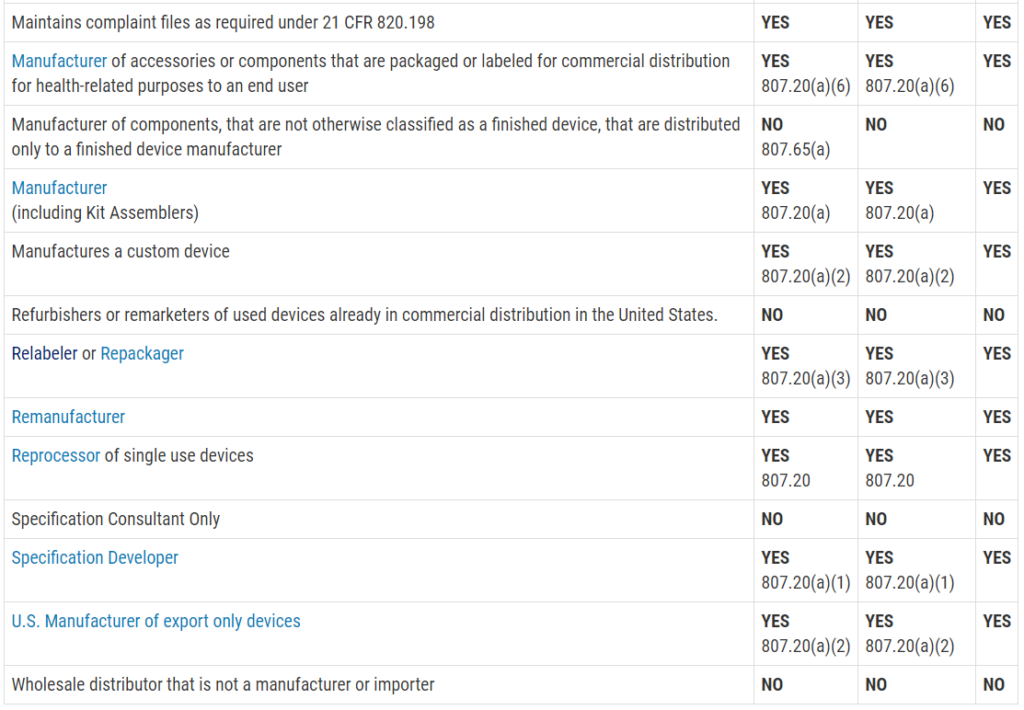

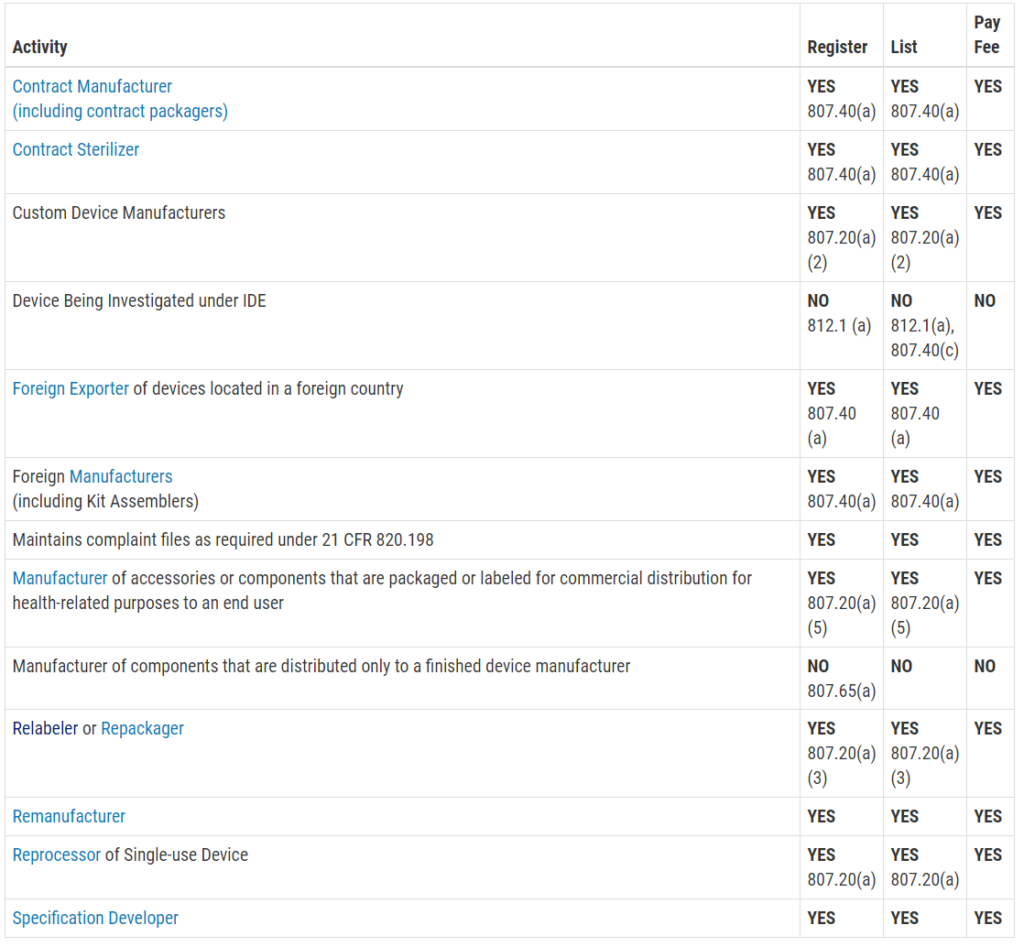

Another reason you are scared of an FDA inspection is that you don’t know exactly when the inspection will be. Only Class III PMA devices, and a few Class II De Novo devices with novel manufacturing processes, require a pre-approval inspection. For the rest of the Class II devices, ORA prioritizes inspections based on risk. There are a few companies prioritized for inspection within the first six months of your initial FDA registration, such as reprocessors of single-use devices and contract sterilizers. For the rest of the Class II device manufacturers, your first inspection should be approximately two years after your company registers with the FDA. If you are located outside the USA (OUS), your first inspection might take three years to schedule. Finally, Class I device manufacturers and contract manufacturers, are unlikely to ever be inspected by the FDA. If you didn’t know what the typical timeline was for ORA to schedule your first inspection, you probably just breathed a HUGE sigh of relief when you read this paragraph.

Even if you already know the approximate timeline and priorities for FDA inspections, it’s normal to feel a little anxiety when the date of your first visit is unknown. Your boss and the rest of the top management are probably feeling just as much anxiety as you are, or even more if they have no idea what the timeline and priorities are. You should make sure that everyone in your company understands what they are supposed to do during an FDA inspection, and if you forget to tell them you might cause a lot of unneeded drama when they find out an FDA inspector is in the front lobby. Preparing for an FDA inspection is no different from conducting a fire drill. Everyone should know the procedure, and you should practice (i.e. conduct a mock FDA inspection). Practice ensures that everyone knows what to do during the first 30 minutes of an FDA inspection, and nobody in your company will panic when an FDA inspector actually arrives.

Let’s define “surprise” visits by an FDA inspector

A surprise visit from an FDA inspector is extremely rare, but in the USA inspectors will call on Friday to confirm that your company will be open the following Monday for an inspection. The FDA has jurisdiction over medical device manufacturers located in the USA, and they are not required to give advanced notice. However, inspectors need time to prepare in advance for their inspection–just like an ISO 13485 auditor. Therefore, before an inspector arrives on-site for a routine (Level 2) inspection, the inspector will first make a courtesy call to the official correspondent identified in your establishment registration.

What happens when an FDA inspector travels outside the USA

In the case of OUS medical device manufacturers, the FDA inspector does not have jurisdiction. Therefore, they will contact the official correspondent 6-8 weeks in advance to schedule an inspection. Inspectors will typically make contact via email, and you may be given a couple of weeks to choose from for the FDA inspection. The duration of your inspection should be 4.5 days. The inspector will arrive on Sunday, and the inspection will begin on Monday morning. The inspector has four major process areas to cover, and Friday morning will be focused on generating a preliminary report of 483 inspection observations. The reason why you can predict this OUS routine with a degree of certainty is two-fold: 1) these are government workers following a procedure, and 2) the FDA inspector needs time to get to the airport for their flight home.

What is the outcome of an FDA inspection?

FDA inspections have three possible outcomes:

- No action indicated – there were no FDA 483 inspection observations identified by the FDA inspector

- Voluntary action indicated – there was at least one FDA 483 inspection observation identified by the FDA inspector, and the FDA inspector requests submission of a CAPA plan to prevent recurrence

- Official action indicated – there was at least one FDA 483 inspection observation identified by the FDA inspector, and the FDA inspector requires submission of a CAPA plan to prevent recurrence; if a plan is not received in 15 business days, a warning letter will automatically be generated on the 16 day

Even in the rare instances with there is “no action indicated” (i.e. best case scenario), I have always noticed one or more things during an FDA inspection that were overlooked and we needed to initiate a new corrective action plan(s). In the other two possible scenarios, the FDA inspector identified the need for one or more corrective action plans. Therefore, regardless of whether your FDA inspection results in the best-case scenario or the worst-case, you will always need to initiate a new corrective action plan(s).

If the outcome is always a CAPA, what should you do?

Give your FDA inspector a big smile and say, “We are a new company, and this is our first FDA inspection. I am also a first-time quality manager. If you find anything that we are doing incorrectly, please let us know and we will make immediate corrections and start working on our CAPA plan.” Making sure that you have a genuine smile is just as important as what you say. Smiling will relax you and the anxiety and stress you are feeling will gradually melt away. Smiling will encourage the FDA inspector to trust you. Maybe your smile will even be contagious.

If you need help responding to an FDA 483 inspection observation, or you want to conduct a mock-FDA inspection, please use our calendly app to schedule a call with a member of our team. We are also hosting a live webinar on FDA inspections on July 26, 2021 @ Noon EDT.

About the Author

Robert Packard is a regulatory consultant with 25+ years of experience in the medical device, pharmaceutical, and biotechnology industries. He is a graduate of UConn in Chemical Engineering. Robert was a senior manager at several medical device companies—including the President/CEO of a laparoscopic imaging company. His Quality Management System expertise covers all aspects of developing, training, implementing, and maintaining ISO 13485 and ISO 14971 certification. From 2009-2012, he was a lead auditor and instructor for one of the largest Notified Bodies. Robert’s specialty is regulatory submissions for high-risk medical devices, such as implants and drug/device combination products for CE marking applications, Canadian medical device applications, and 510(k) submissions. The most favorite part of his job is training others. He can be reached via phone 802.258.1881 or email. You can also follow him on Google+, LinkedIn or Twitter.

Smile, because you should never be scared of a surprise FDA inspector Read More »