eSTAR Project Management

Using the new FDA eSTAR template also requires a new process for eSTAR project management to prepare your 510k and De Novo submissions.

Outline of ten (10) major changes resulting from the new FDA eSTAR template

As of October 1, 2023, all 510k and De Novo submissions to the FDA now require using the new FDA eSTAR template and the template must be uploaded to the FDA Customer Collaboration Portal (CCP). Yesterday the FDA published an updated guidance explaining the 510k electronic submission requirements, but there are ten (10) major changes to Medical Device Academy’s submission process resulting from the new eSTAR templates:

- We no longer need a table of contents.

- We no longer use the volume and document structure.

- We are no longer required to conform to sectioning or pagination of the entire submission.

- We no longer worry about the RTA screening or checklist (it doesn’t exist).

- We no longer bother creating an executive summary (it’s optional).

- We no longer have a section for Class 3 devices, because there are no Class 3 510(k) devices anymore.

- We no longer use FDA Form 3514, because that content is now incorporated into the eSTAR.

- We no longer create a Declaration of Conformity, because the eSTAR creates one automatically.

- We no longer recommend creating a 510(k) Summary, because the eSTAR creates one automatically

- We no longer use FedEx, because we can upload to FDA CCP electronically instead.

What is different in the 510k requirements?

Despite all the perceived changes to the FDA’s pre-market notification process (i.e., the 510k process), the format and content requirements have not changed much. The most significant recent change to the 510k process was the requirement to include cybersecurity testing.

Outline of eSTAR Project Management

There were 20 sections in a 510k submission. Medical Device Academy’s consulting team created a template for the documents to be included in each section. eSTAR project management is different because there are no section numbers to reference. To keep things clear, we recommend using one or two words at the beginning of each file name to define the section it belongs in. The words should match up with the bookmarks used by the FDA. However, you should be careful not to make the file names too long. Below is a list of all of the sections:

- Administrative Information;

- Device Description;

- Predicates and Substantial Equivalence;

- Benefits, Risks, and Mitigation Measures;

- Labeling;

- Reprocessing, Sterility, and Shelf-life;

- Biocompatibility;

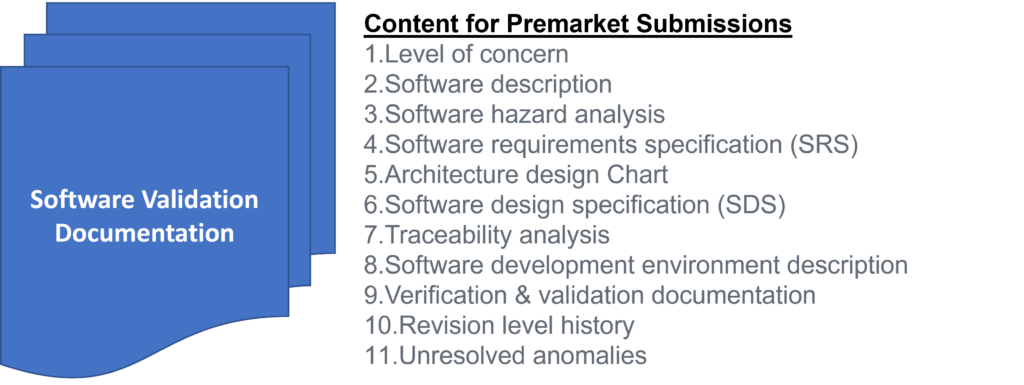

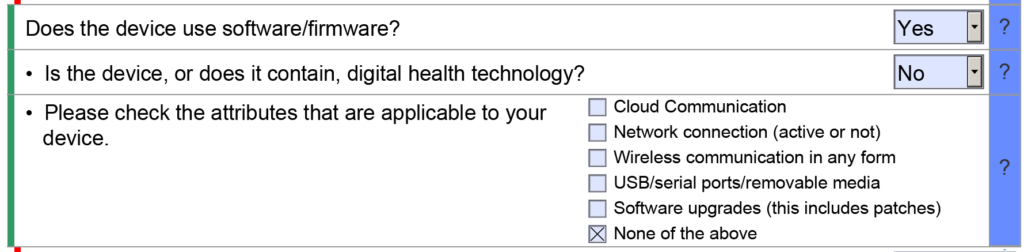

- Software/Firmware

- Cybersecurity

- Interoperability

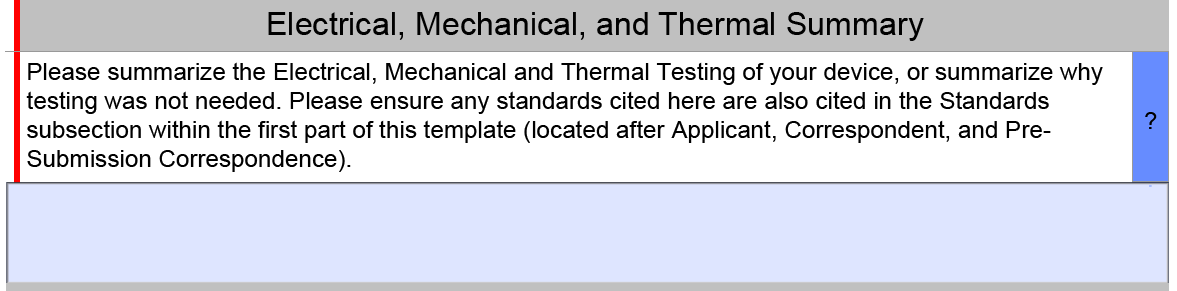

- EMC, Wireless, Electrical, Mechanical, and Thermal Safety;

- Performance Testing;

- Quality Management; and

- Administrative Documentation.

The Benefit, Risks, and Mitigation Measures Section only applies to De Novo Classification Requests. The Quality Management Section includes subsections for Quality Management System Information, Facility Information, Post-Market Studies, and References. However, only the References subsection will be visible in most submissions because the other three subsections are part of the Health Canada eSTAR pilot. Other sections and subsections will be abbreviated or hidden depending on the dropdown menu selections you select in the eSTAR. For example, the cybersecurity section will remain hidden if your device does not have wireless functionality or a removable storage drive.

A Table of Contents is no longer required for 510k submissions

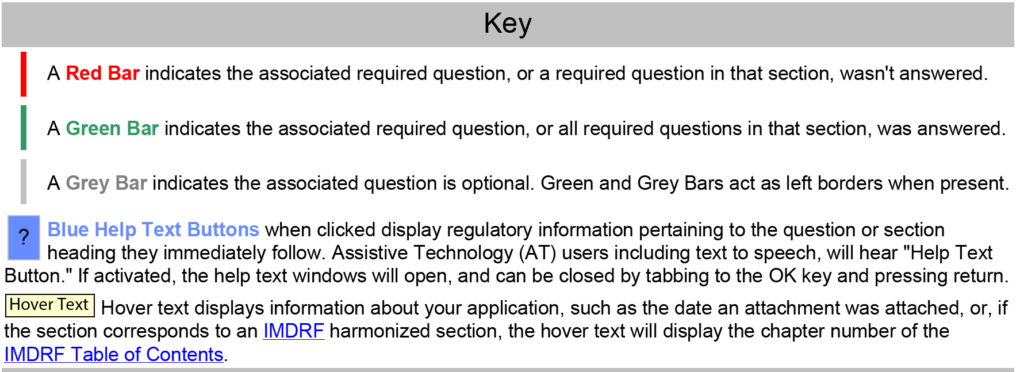

510k submissions using the FDA eCopy format required a Table of Contents, and Medical Device Academy used the Table of Contents as a project management tool. Sometimes, we still use our Table of Contents template to communicate assignments and manage the 510k project. The sections of the Table of Contents would also be color-coded green, blue, yellow, and red to communicate the status of each section. FDA eSTAR project management uses a similar color coding process with colored bars on the side of the template to indicate if the section is incomplete, complete, or optional.

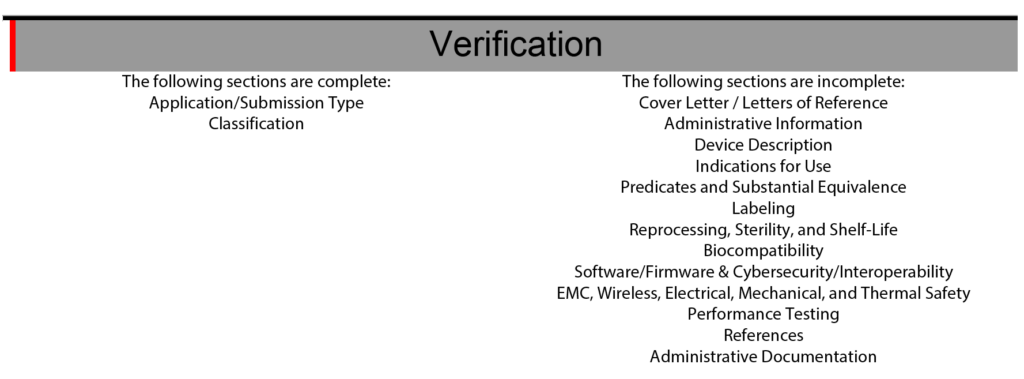

The eSTAR also has a verification section at the end of the template to help with eSTAR project management. The verification section lists each of the 13 major sections of an FDA eSTAR. When the sections are completed, the section’s name automatically moves from the right side of the verification section to the left side. During the past two years (2021 – 2023) of implementing the eSTAR template, I have slowly learned to rely only on the eSTAR to communicate the status of each section. To assign responsibilities for each section of the 510k submission, we still use the Table of Contents simple lists and project management tools like Asana. Using the eSTAR verification section to check on the status of each 510k section also increases our team’s proficiency with the eSTAR every time we use it.

Using Dropbox for eSTAR project management

PreSTAR templates for a Q-Sub meeting are approximately half the length (i.e., 15 pages instead of 30+ pages) of an eSTAR template, and the 510k submission requires far more attachments than a Q-Sub. Therefore, we can usually email a revised draft of the PreSTAR to a team member for review, but we can’t use email to share a nearly complete eSTAR with a team member. Therefore, Medical Device Academy uses Dropbox to share revisions of the eSTAR between team members. Some of our clients use One Drive or Google Drive to share revisions. We also create sub-folders for each type of testing. This keeps all of the documents and test reports for a section of the eSTAR in one place. For example, the software validation documentation will be organized in one sub-folder of the Dropbox folder for a 510k project.

When using FDA eCopies instead of the FDA eSTAR template, we used twenty subfolders labeled and organized by volume numbers 1-20. Some of those 20 sections are now obsolete (e.g., Class III Summary), and others (e.g., Indications for Use) are integrated directly into the eSTAR template. Therefore, a team may only need 8-10 sub-folders to organize the documents and test reports for a 510k project. We typically do not attach these documents and test reports until the very end of the submission preparation because if the FDA releases a new version of the eSTAR, the attachments will not export from an older version of the eSTAR to the new version.

Coordination of team collaboration is critical to successful eSTAR project management

In the past, Medical Device Academy always used a volume and document structure to organize an FDA eCopy because this facilitated multiple team members simultaneously working on the same 510k submission–even from different countries. Many clients will use SharePoint or Google Docs to facilitate simultaneous collaboration by multiple users. Unfortunately, the eSTAR cannot be edited by two users simultaneously because it is a secure template that can only be edited in Adobe Acrobat Pro. Therefore, the team must communicate when the eSTAR template is being updated and track revisions. For communication, we use a combination of instant messenger apps (e.g., Slack or Whatsapp) and email, while revisions are tracked by adding the initials and date of the editor to the file name (e.g., nIVD 4.3 rvp 12-5-2023.pdf).

Importance of peer reviews

Each section of the FDA eSTAR must be completed before the submission can be uploaded to the Customer Collaboration Portal (CCP). If the FDA eSTAR is incomplete, the CCP will identify the file as incomplete. You will not be able to upload the file. If questions in the eSTAR are incorrectly answered, then sections that should be completed may not be activated because of how the questions were answered. Below are two examples of how the eSTAR questions can be incorrectly answered.

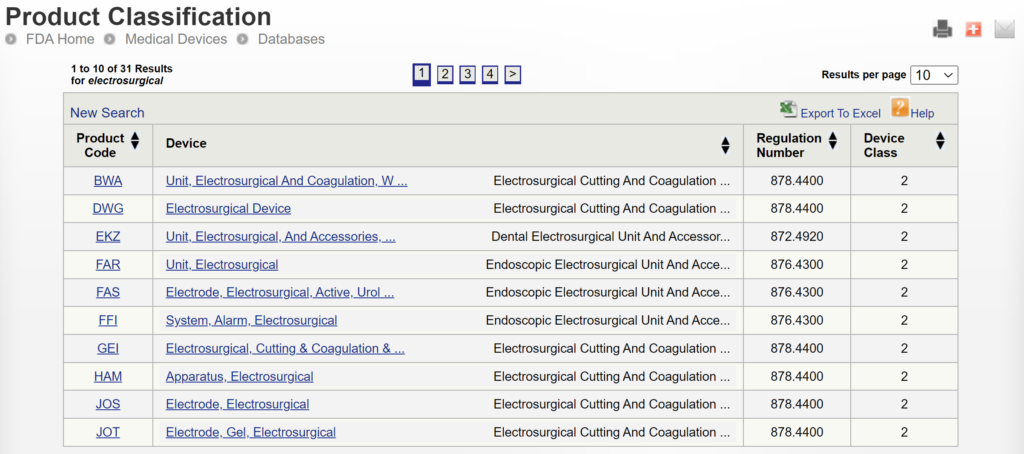

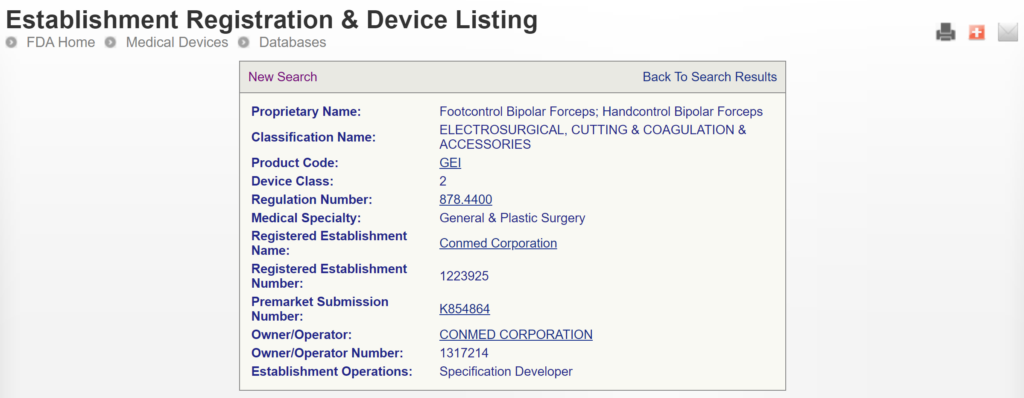

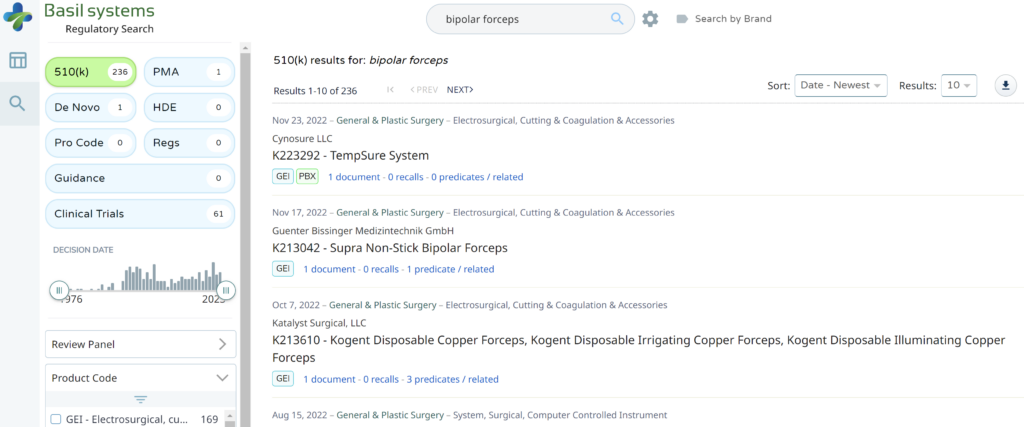

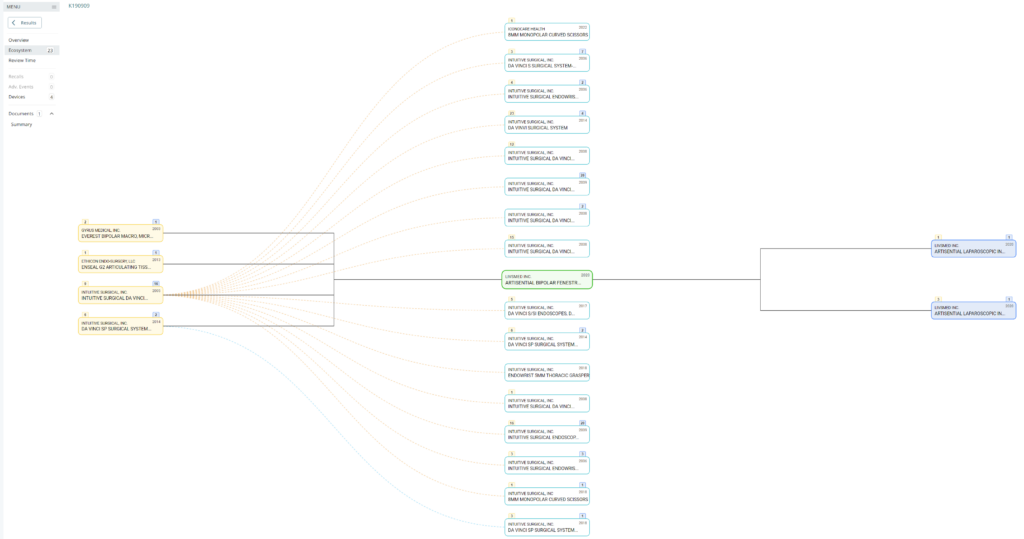

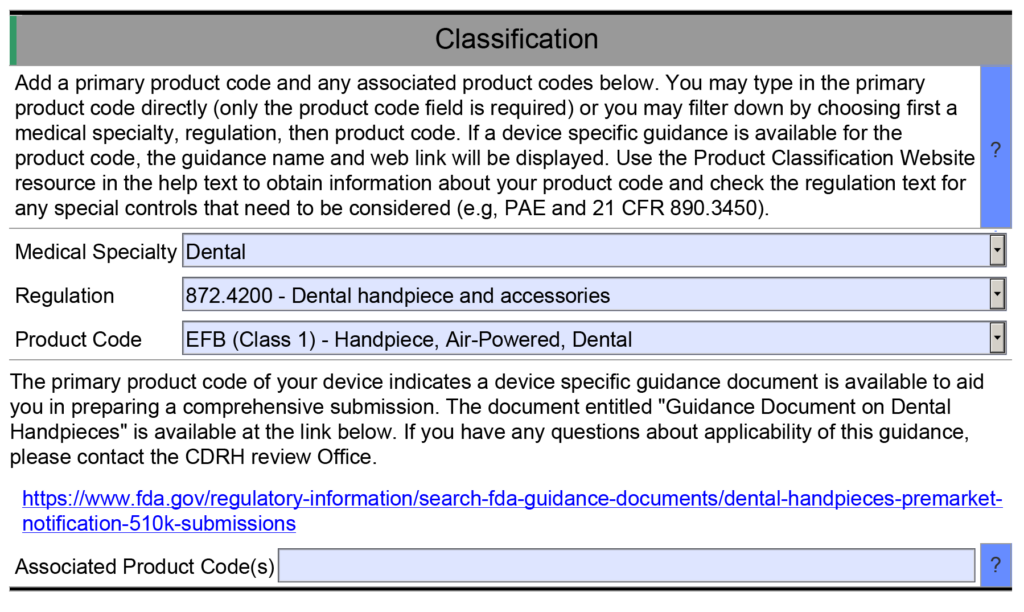

- Example 1 – One of the helpful resource features of the FDA eSTAR is that many fields are populated with a dropdown menu of answers. One example is found in the Classification section of the eSTAR. This section requires the submitter to identify the device’s classification by answering three questions: 1) review panel, 2) classification regulation, and 3) the three-letter product code. Each of these fields uses a dropdown menu to populate the field, and the dropdown options for questions two and three depend on answers to the previous question. However, if you manually type the product code into the field for the third question, then the eSTAR will not identify any applicable special controls guidance documents for your device. Unless you are already aware of an applicable special controls guidance document, you will answer questions in the eSTAR about special controls with “N/A.” The eSTAR will only identify a special controls guidance document for your device if you select a product code from the dropdown menu, but the FDA reviewer knows which special controls guidance documents are applicable. This is why the FDA performs a technical screening of the eSTAR before the substantive review begins.

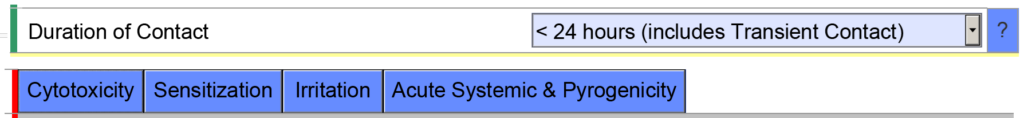

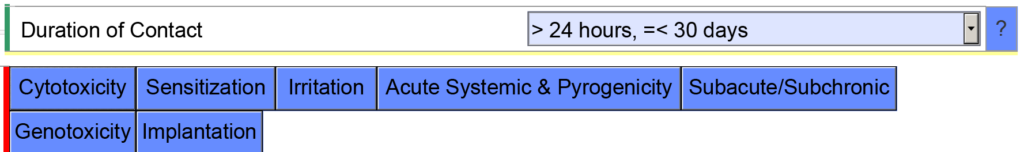

- Example 2 – If you indicate the cumulative duration of contact for an externally communicating device < 24 hours, the eSTAR template will expect you to evaluate the following biocompatibility endpoints: cytotoxicity, sensitization, irritation, systemic toxicity, and pyrogenicity.

However, if you indicate the cumulative duration of contact is < 30 days, the eSTAR template will be populated with additional biocompatibility endpoints. The eSTAR doesn’t know what the cumulative duration of use is, but the FDA reviewer will. This is why the FDA performs a technical screening of the eSTAR before the substantive review begins.

To make sure that all of the sections of your submission are complete, it’s helpful to have a second person review all of the answers to make sure that everything was completed correctly. Even experienced consultants who prepare 510k submissions every week can make a mistake and incorrectly answer a question in one of the eSTAR fields. Therefore, you shouldn’t skip this critical QC check.

Additional 510k Training

The 510k book, “How to Prepare Your 510k in 100 Days,” was completed in 2017, but the book is only available as part of our 510k course series consisting of 58+ webinars. Please visit the webinar page to purchase individual webinars.

eSTAR Project Management Read More »