ALARP vs As far as possible – Deviation #3

This third blog in a seven-part series reviews deviation #3, ALARP vs. “As far as possible,” with regard to risk reduction.

In 2012, the European National (EN) version of the Medical Device Risk Management Standard was revised, but there was no change to the content of Clauses 1 through 9. Instead, the European Commission identified seven content deviations between the 14971 Standard and the requirements of three device directives for Europe. This seven-part blog series reviews each of these changes individually and recommends changes to be made to your current risk management policies and procedure.

In 2012, the European National (EN) version of the Medical Device Risk Management Standard was revised, but there was no change to the content of Clauses 1 through 9. Instead, the European Commission identified seven content deviations between the 14971 Standard and the requirements of three device directives for Europe. This seven-part blog series reviews each of these changes individually and recommends changes to be made to your current risk management policies and procedure.

Note: This is 2013 blog that will be updated in the near future, but the following link is for our current risk management training.

Risk reduction: “As Far As Possible” (AFAP) vs. “As Low As Reasonably Practicable” (ALARP)

The third deviation is specific to the reduction of risk. Design solutions cannot always eliminate risk. This is why medical devices use protective measures (i.e., – alarms) and inform users of residual risks (i.e., – warnings and contraindications in an Instructions For Use (IFU). However, Essential Requirement 2 requires that risks be reduced “as far as possible.” Therefore, it is not acceptable to only reduce risks with cost-effective solutions. The “ALARP” concept has a legal interpretation, which implies financial considerations. However, the European Directives will not allow financial considerations to override the Essential Requirements for the safety and performance of medical devices. If risk controls are not implemented, the justification for this must be on another basis other than financial.

There are two acceptable reasons for not implementing certain risk controls. First, risk control will not reduce additional risk. For example, if your device already has one alarm to identify a battery failure, a second alarm for the same failure will not reduce further risk. The redundant alarms are often distracting, and too many alarms will result in users ignoring them.

The second acceptable reason for not implementing a risk control is that there is a more effective risk control that cannot be simultaneously implemented. For example, there are multiple ways to anchor orthopedic implants to bone. However, there is only enough real estate to have one fixation element at each location. If a femoral knee implant is already being anchored to the femur with metal posts and bone cement, you cannot also use bone screws at the same location on the femur to anchor the implants in place.

ALARP does not reduce risk “As far as possible”

Annex D.8 in ISO 14971, recommends the ALARP concept in Clause 3.4 of the 14971 Standard. Therefore, the risk management standard is contradicting the MDD. This contradiction is the primary reason why medical device companies should discontinue the use of phthalates and latex for most medical devices. Even though these materials are inexpensive solutions to many engineering challenges presented by medical devices, these materials present risks that can be avoided by using more expensive materials that are not hazardous and do not pose allergic reactions to a large percentage of the population. The use of safer materials is considered “state-of-the-art,” and these materials should be implemented if the residual risks, after implementation of the risk control (i.e., – use of a safer material) are not equal to, or greater than, the risk of the cheaper material.

Recommendation for eliminating ALARP

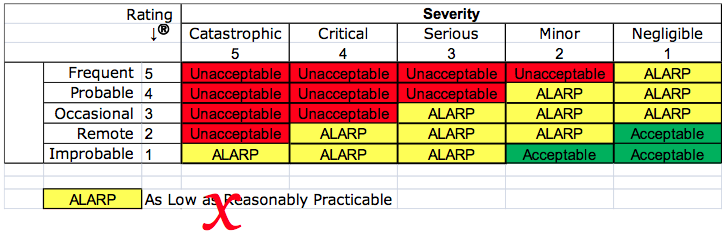

Your company may have created a risk management procedure that includes a matrix for severity and probability. The matrix is probably color-coded to identify red cells as unacceptable risks, yellow cells that are ALARP, and green cells that are acceptable. To comply with EN ISO 14971:2012, the “yellow zone” should not be labeled as ALARP. A short-term solution is to simply re-label these as high, medium, and low risks. Unfortunately, renaming the categories of risk high, medium, and low will not provide guidance as to whether the residual risk is reduced “as far as possible.”

Resolution to this deviation

As companies become aware of this deviation between the 14971 Standard and the Essential Requirements of the device directives, teams that are working on risk analysis, and people that are performing a gap analysis of their procedures will need to stop using a matrix, like the example above. Instead of claiming that the residual risks are ALARP, your company will need to demonstrate that risks are reduced AFAP, by showing objective evidence that all possible risk control options were considered and implemented. Your procedure or work instruction for performing a risk control option analysis may currently state that you will apply your risk management policy to determine if additional risk controls need to be applied, or if the residual risks are ALARP.

This procedure or work instruction needs to be revised to specify that all risk control options will be implemented unless the risk controls would not reduce risks further, or the risk controls are incompatible with other risk controls. Risk control options should never be ruled out due to cost.

ALARP vs As far as possible – Deviation #3 Read More »