How quickly will RTA policy take effect for cybersecurity devices?

Breaking news! The FDA just released new guidance on the refusal to accept (RTA) policy for cybersecurity devices.

Where can I find the new cybersecurity devices guidance?

The new guidance is titled “Cybersecurity in Medical Devices: Refuse to Accept Policy for Cyber Devices and Related Systems Under Section 524B of the FD&C Act,” and you can download a copy of the PDF directly from our website. This is the first time the FDA has created a definition for a “cyber device,” but this guidance is specific to the refusal to accept policy (RTA) rather than guidance for the format and content of pre-market notification (i.e., 510k) If you want to learn about new guidance documents as they are released, we recommend that you sign up for FDA email notifications. If you want to be notified of when our new blogs are posted, subscribe to our blog email notification list on this page.

What is a “cyber device” in the context of this cybersecurity devices guidance and submissions?

This new guidance defines “cyber device” using the following language:

- includes software validated, installed, or authorized by the sponsor as a device or in a device;

- has the ability to connect to the internet; and

- contains any such technological characteristics validated, installed, or authorized by the sponsor that could be vulnerable to cybersecurity threats.

What does “refusal to accept” (RTA) mean?

“Refusal to accept” or (RTA) is a policy that the FDA implemented for pre-market notification submissions (i.e., 510k) in 2012. The process occurs during the first 15 calendar days of the FDA review process. The FDA assigns a preliminary reviewer to perform the RTA screening of the submission, and the person completes an RTA checklist. The FDA substitutes an RTA screening with a technical screening for FDA eSTAR templates, and this is one of the reasons why Medical Device Academy uses the FDA eSTAR templates for all 510k submissions and De Novo classification requests instead of using the older 510k format and content requirements with 20 sections.

When will the FDA begin rejecting submissions during the RTA processes?

The FDA states directly in the guidance document that they will not reject submissions for cybersecurity for the balance of FY 2023 (i.e., before October 1, 2023). The wording used by the FDA is: “The FDA generally intends not to issue “refuse to accept” (RTA) decisions for premarket submissions for cyber devices that are submitted before October 1, 2023, based solely on information required by section 524B of the FD&C Act. Instead, the FDA will work collaboratively with sponsors of such premarket submissions as part of the interactive and/or deficiency review process.” We believe the FDA will update the eSTAR template to include requirements for cybersecurity on October 1, 2023. It will not be possible to submit a 510k that does not include the cybersecurity requirements in future eSTAR templates, because the eSTAR automatically verifies the completion of each section in the template.

Will there be another cybersecurity guidance released soon?

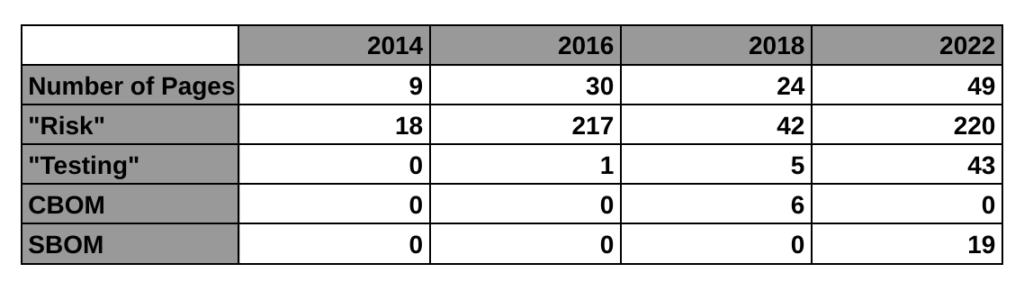

The FDA announced last October that a new cybersecurity guidance would be replacing the 2014 final guidance for cybersecurity. A draft was released in 2018, and an updated draft was released in 2022. The final updated guidance is included in the A-list of FDA priorities for final guidance documents, but the updated final version has not been released yet. The FDA webpage for cybersecurity was updated to include this new guidance on RTA policy for cybersecurity devices. We believe this indicates that the updated final version will be released soon. When it is released, we will publish a new blog about that guidance.

How quickly will RTA policy take effect for cybersecurity devices? Read More »