CE Marking Approval of a Medical Device (Case Study)

This case study explains the process for CE Marking approval of a medical device under the EU MDD regulations.

For this case study, I selected the same hypothetical client that I chose for my case study on Canadian Medical Device Licensing and a 510k submission to the US FDA. The product is a cyanoacrylate adhesive sold by the makers of Krazy Glue®. This hypothetical client wants to expand its target market to include the healthcare industry by repackaging and marketing the product as a topical adhesive in Europe.

My client called to ask if I could help obtain CE Marking approval. In Europe, cyanoacrylate is a medical device when it is used as a topical adhesive. My first step is to determine the device classification as per Annex IX in the Medical Device Directive (93/42/EEC as modified by 2007/47/EC). Instead of relying solely upon the Directive, I use guidance documents published on the Europa website–specifically MEDDEV 2.4/1 rev 9 (the following link explains the European MEDDEV guidance documents – http://bit.ly/Whats-a-MEDDEV).

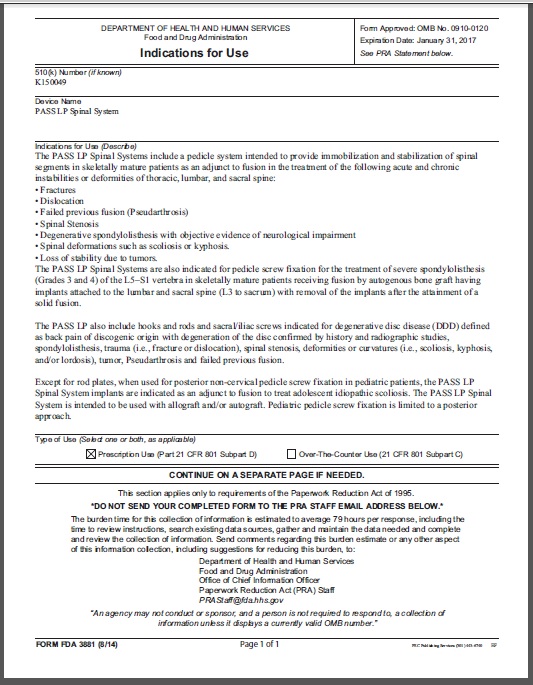

I identified three potential device classifications: 1) Class 1 as per Rule 4 (a non-invasive device which comes into contact with injured skin, if the device is intended to be used as a mechanical barrier, for compression or absorption of exudates); 2) Class 2a as per Rule 7 (a surgically invasive device intended for short-term use [i.e., < 30 days] are in Class 2a; and 3) Class 2b as per Rule 8 (an implantable device). These three applications match the three possible indications that I identified when I was reviewing classifications for Canadian Medical Device Licensing for this product.

If this device were not required to be “sterile,” then a Class 1 device could use the Annex VII route of conformity (i.e., self-declaration). However, even generic bandages are sold as sterile devices. Therefore, whether the device is a sterile Class 1 device or a Class 2a device, obtaining CE Marking approval will still require a Notified Body’s review and approval. The most common route would be the Annex V route of conformity. If my client were to launch their product as a “glue” for internal use, then the device would require an Annex II.3 Full Quality System Certificate or the combination of an Annex V Certificate and a Type Examination Certificate (i.e., Annex III).

STOP!

The previous paragraph was hard to understand, but the source of this jargon is Article 11 of the Medical Device Directive. This one section is the best practices in European legalese. If you want to make something almost unintelligible, copy Article 11. If you’re going to understand this stuff, a flow chart of the various routes to conformity is as good as it gets (still hard to understand, but fewer words). The following simplified table is what I use in my CE Marking webinar:

What you need to know…

My client only has one product family, and they are currently selling the product in Canada for external use by healthcare professionals—not as an implant. Therefore, the device is a Class 2a device requiring an Annex V certificate. My client will need to do the following:

- Select a Notified Body

- Submit a Technical File for review and approval

- Select a European Authorized Representative, because my client does not have a physical presence in Europe

Fortunately, my client already obtained an ISO 13485:2003 certificate with CMDCAS from their current registrar as part of the Canadian Licensing process. Therefore, the changes required for the Quality System consist of adding a few work instructions to meet European-specific requirements, such as vigilance reporting, creating a technical file, and performing clinical evaluations. My client also needs to add the European Requirements as an applicable regulatory requirement in the Quality Manual.

The more significant challenge is an assembly of a Technical File for submission. Since the product is already on the market in Canada, all of the technical requirements have been met. The documentation of these requirements now needs to be converted into a format acceptable to a Notified Body. There are three recommended strategies:

- Whatever the Notified Body prefers. Some of the Notified Bodies have a checklist of requirements for a Technical File. If such a list exists, the client should organize the Technical File in the same order.

- The GHTF STED format (GHTF/SG1/N011:2008). The Global Harmonization Task Force (http://bit.ly/GHTFSTEDGuidance) published this guidance document to standardize the format for submission of regulatory submissions. This is the format required for Class III and IV Canadian medical device license applications. This is also the format specified in the proposed EU Medical Device Regulations that is expected to be released in 2015.

- The NB-MED recommended format (NB-MED 2.5.1/rec 5). This document was created by the “Big 5” Notified Bodies. It provides a template in a two-part format for submissions. This was the format I used most often for auditing files and for creating new files. However, the proposed EU Regulations that are anticipated for release in 2015 are closer to the format of the GHTF guidance. Therefore, I no longer recommend this format.

My client chose option 3 for organizing their Technical File because they have full reports for each of the verification and validation tests that were performed, but creating summaries for each report would take longer than assembling a Technical File with copies of each of these full reports.

In all, I estimate that the overall timescale for completing this project is about 60 days–not including review by the Notified Body. Therefore, I suggested that the client obtain a quotation from their registrar for an Annex V Certificate. In addition, I suggested hiring a consultant from Medical Device Academy to help them with the preparation of a Clinical Evaluation. Before 2010, Clinical Evaluations were only required for high-risk devices. As part of the new MDD, clinical evaluations are now needed for all devices. Since the use of and risks associated with cyanoacrylates is well characterized in published literature, my client may use a literature search method for preparing a Clinical Evaluation as per MEDDEV 2.7/1 rev 3.

My client hired an Authorized Representative to handle European registration, receive customer complaints, and to act as a liaison with the Competent Authority in the event of an adverse event. An Authorized Representative Agreement was signed, and the Authorized Representative recommended a few corrections to procedures they reviewed as part of entering the contract with a new client.

The company also hired another clinical consultant from our firm to complete a literature search and write a Clinical Evaluation in four weeks. The complete Technical File was assembled and submitted to the Notified Body electronically with seven weeks of starting the project. The Notified Body’s first round of questions was received within six weeks. The client and I prepared responses to the questions in a week and submitted them to the Notified Body. Fortunately, the responses were thorough, and the Technical File was well-organized from the start. The Notified completed their final review and recommended the product for CE Marking within three more weeks. The Notified Body conducted two-panel reviews to verify the technical, regulatory, and risk aspects of the submission. Finally, the Annex V certificate was received 12 weeks after the initial submission of the Technical File.

If you are interested in additional training or assistance with CE Marking of medical devices, please email Rob Packard (mail to: rob@fdaestar.com). We have standardized procedures to meet each of the requirements in the European Regulations and a couple of webinar recordings that explain both the Medical Device Directive and how to create a technical file or design dossier.

CE Marking Approval of a Medical Device (Case Study) Read More »