ISO 19011 – Do you need this quality system auditing standard?

Read this article to learn why ISO 19011 standard is a vital guidance for anyone that audits quality systems or manages an audit program.

What is ISO 19011?

ISO 19011 is a seven-part international standard for auditing management systems. The standard defines the eight principles of auditing (e.g., the process approach to auditing), provides guidance on managing audit programs and conducting audits, and includes recommendations for evaluating people for competency. There is also an appendix with details on conducting on-site and remote audits.

If you have ever taken a lead auditor course for ISO 13485, or one of the other quality management system standards, one of the critical handouts for the class should have been ISO 19011. The title is “Guidelines for Auditing Quality Management Systems.” In 2018, ISO 19011 was updated, and the changes were not superficial. If you need to purchase a copy of ISO 19011:2018, the Estonian Center for Standardization and Accreditation is the least expensive source we know.

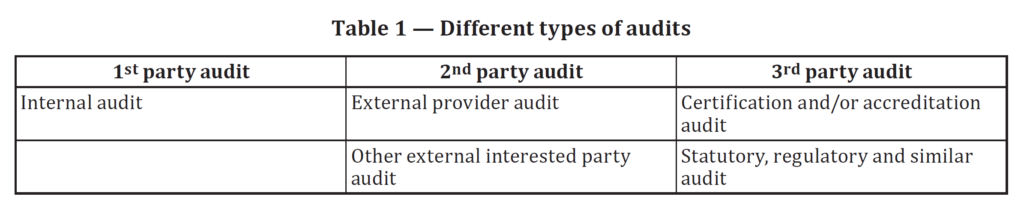

ISO 19011 covers the topic of quality management system auditing. This Standard provides guidance on managing audit programs, conducting internal and external audits, and determining auditor competency. One of the most common points of confusion in the lead auditor course is the difference between first, second, and third-party audits. In the first edition of this Standard, the difference between first, second, and third-party audits was just a note at the bottom of page one and the top of page two. The note was also not clear. In the second edition of 19011, in Table 1 (reproduced below), the difference between these three types of auditing is crystal clear. Table 1 was modified further in the 3rd edition to include a bottom row that remains unchanged in the 3rd edition, released in 2018.

Figure 1, found in Clause 5.1 of the 2nd edition, was combined with Figure 2, found in Clause 6.1 of the 2nd edition. The combined figure is now Figure 1 in the 3rd edition. The combined scope of Figure 1 is now a “Process flow for the management of an audit program” and a “Process flow for conducting an audit.” The figure categorizes the various stages of audit program management and conducting an audit into the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle. We highly recommend this style for presenting any process in your internal procedures as an example of best practices in writing an SOP. The flow chart even references each of the clauses in the Standard.

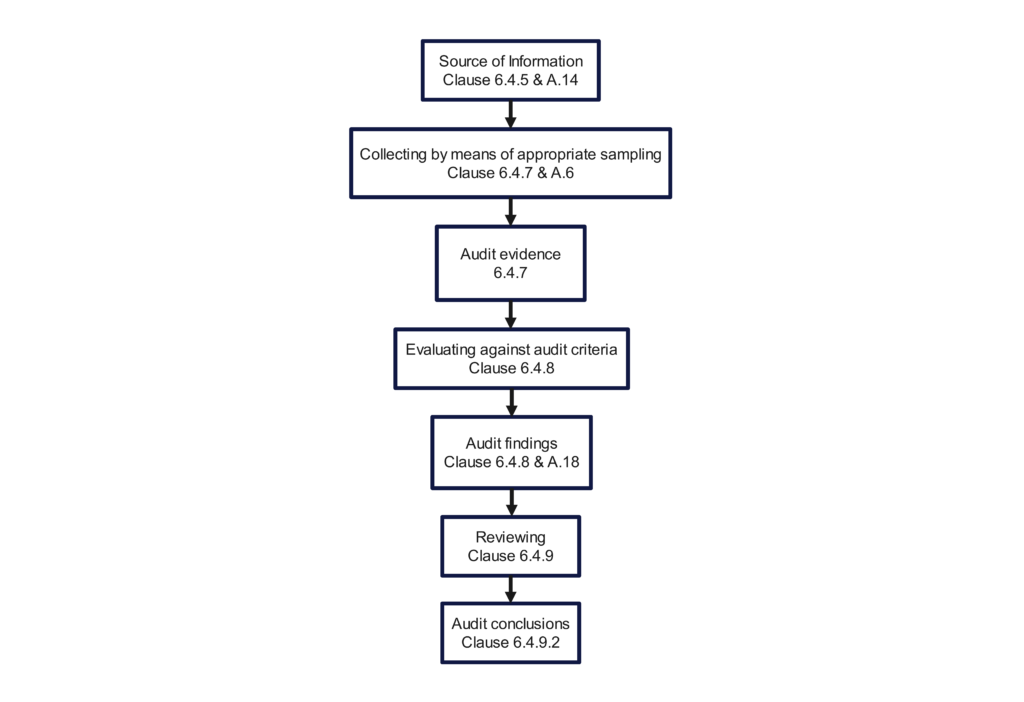

The 2018 version still includes an opening meeting checklist (i.e., Clause 6.4.3) and a closing meeting checklist (i.e., Clause 6.4.10). Figure 3 in the 2nd edition, “Overview of the process of collecting and verifying information,” was a poor example of a flow chart. The committee did not update the figure when the standard was updated for the 3rd edition. Therefore, we updated the figure below to provide additional traceability to the Clauses of the Standard. If you incorporate this figure into your quality auditing procedure, you should substitute references to your procedure’s sections instead of the clauses of the standard.

Competency Requirements in ISO 19011

Many audit procedures neglect to define the qualifications and methods for determining the competency of the audit program manager. Clause 5.3.2 tells you how. Put it in your own procedure. Most of the procedures we read include qualifications for a “Lead Auditor,” but we seldom see anything regarding competency. Unfortunately, this Standard only explicitly addresses the “Lead Auditor” competency in a two-sentence paragraph—Clause 7.2.5. When we teach people how to be Lead Auditors, we spend more than an hour on this topic alone.

The Standard would be more effective by providing an example of how third-party auditors become qualified as a Lead Auditor. Third-party accreditation requires the auditor to be an “acting lead” for audit preparation, opening meetings, conducting the audit, closing meetings, and final preparation/distribution of the audit report. This must be performed for 15 certification audits (i.e., – Stage 2 certification or re-certification), and another qualified lead auditor must evaluate you and provide feedback.

Appendices in ISO 19011

The appendices were the last significant additions to this Standard in 2011 (i.e., 2nd edition). Annex A provided examples of discipline-specific knowledge and skills of auditors. This section was eliminated from the 3rd edition of ISO 19011:

“Due to the large number of individual management system standards, it would not be practical to include competence requirements for all disciplines.” – Copied from the Foreward

I think providing adding a short Annex to each management system standard that defines recommended discipline-specific knowledge would be helpful. Still, that kind of change would need to be initiated with the next version of ISO 9001.

Appendix B in the 2nd edition is now Appendix A in the 3rd edition of ISO 19011. A table (Table A.1 – Audit Methods) compares conducting on-site and remote audits. We were pleased to see that conducting interviews is a significant part of remote auditing in this table. Section A.17 in the appendix provides suggestions for conducting interviews. Still, if you exhibit all 13 professional behavior traits found in Clause 7.2.2, you don’t need advice on speaking with people. For the rest of us mortals, we could use a five-day course on interviewing alone. To improve your skills in this area, ask an experienced auditor with solid interviewing skills to watch and comment on a recording of a virtual audit you perform. Watching yourself audit is cringe-worthy, but we guarantee you will improve.

What are the primary changes to the 2018 version of the standard?

There are seven main differences between the second edition, published in 2011, and the third edition of ISO 19011, released in 2018:

- addition of a seventh principle of auditing in sub-clause 4(g) (i.e., risk-based approach);

- more guidance on audit program management in Clause 5, including audit program risk;

- expansion of Clause 6 on conducting an audit–especially Clause 6.3 on audit planning;

- expansion of auditor competence requirements in Clause 7;

- updating of terminology to emphasize processes rather than objects;

- removal of an annex containing competence requirements for specific quality management systems;

- expansion of Annex A to include guidance on new auditing concepts such as remote audits.

Risk-based auditing is the most significant change in the 2018 version of ISO 19011

One of the main differences between ISO 19011:2018 and the previous 2011 version is the addition of a “risk-based approach” to the principles of auditing. Specifically, clause 4(g) of the guidelines for auditing management systems is, “The risk-based approach should substantively influence the planning, conducting and reporting of audits to ensure that audits are focused on matters that are significant for the audit client, and for achieving the audit program objectives.” A lot of people are unsure of what is meant by a risk-based approach. Still, the key to understanding this is to focus on the definition of risk. From a product perspective, the risk is the “combination of the probability of occurrence of harm and the severity of that harm.” From a process perspective, the risk is the “effect of uncertainty on an expected result” (ISO 9001:2015, clause 3.09). Therefore, auditors should emphasize medical devices with the highest severity of harm and devices with a high probability of hazards or hazardous situations. When an auditor focuses on a process rather than a specific medical device, auditors should emphasize any processes that are not under control and any recent process changes.

What is risk-based auditing?

Risk-based auditing considers the risks of failing to achieve audit objectives and the opportunities created by choosing various audit methods and strategies. For example, a desktop audit of procedures might be appropriate if you are conducting your first internal audit for a new quality system. Alternatively, a desktop audit would be a waste of time if you are auditing a mature quality system where very few changes to procedures have been made in the past year. Using the element approach to auditing is unlikely to add much value. Audits are meant to be a sampling. Therefore, you should focus on areas of importance where previous nonconformities were identified, any new products or processes, and anything that changed significantly.

Auditor selection should also be risk-based

Suppose you are conducting a supplier audit as part of your initial supplier qualification for a critical component supplier or contract manufacturer. In that case, you should consider doing a team audit with a multi-disciplinary team. This is a risk-based approach to the supplier qualification process, which ensures that subject matter experts evaluate each process instead of auditors with a general quality assurance background. This approach also forces more of your personnel to introduce themselves to the new supplier, and the audit will develop more reliable communication channels between your two companies. Alternatively, if you are conducting a routine internal audit of a production process, you might select a new lead auditor to conduct the audit. You don’t expect any significant findings in a routine internal audit of an established production process. In your role as an audit program manager, you need to match the new lead auditor to a process that will force them to look at all aspects of the process approach to auditing. Specifically, process validation, calibration, maintenance, and process monitoring may not apply to other administrative process areas, such as purchasing.

Risk-based auditing should influence your auditing schedule

The frequency of auditing suppliers and internal process areas should reflect the associated risks. Therefore, when you create or update your auditing schedule, you should consider the risk level of the products being audited and the process being audited. Production processes with a moderate or high level of non-conforming products may need to be audited more than once yearly. Still, a supplier with an excellent track record of extremely high quality and on-time delivery may be audited in alternating years. If you previously scheduled a remote audit, you may want to alternate to conducting an on-site audit the next time.

The duration of your audits should not always be the same either. Suppose one production process makes one product in low volume, and another production process makes multiple products in high volume. In that case, you should not schedule a two-hour internal audit for both processes every year. The low-volume production process may only need a one-hour audit once per year. In contrast, the high-volume process may require a four-hour internal audit or multiple annual audits.

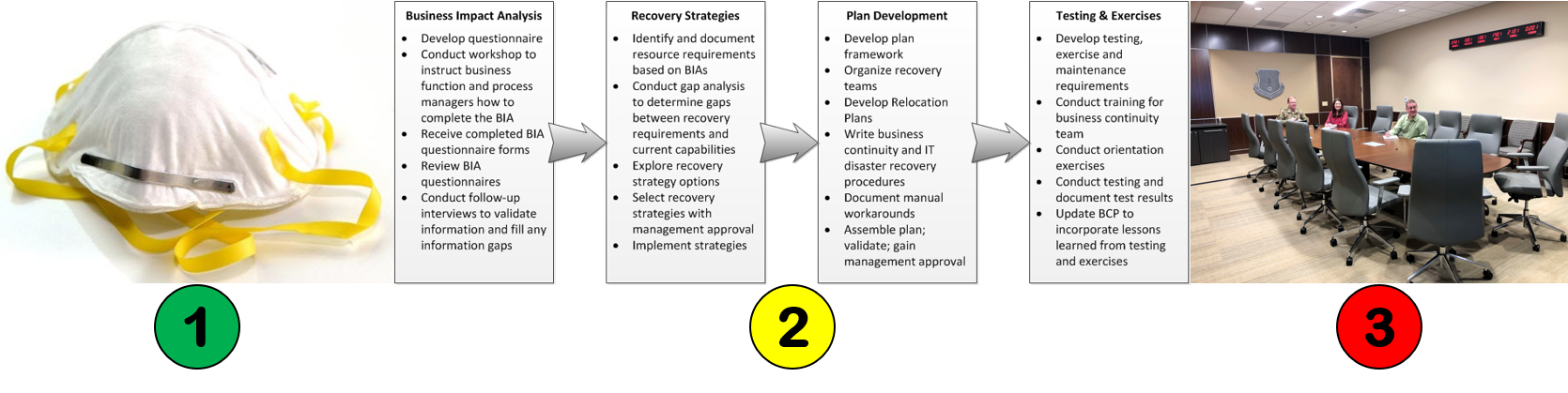

Risk-based auditing applied to remote supplier auditing

The risk-based auditing approach was added to ISO 19011:2018 as the seventh principle of auditing. This represents the most significant change to that standard, but how does it apply to remote auditing? Despite the opportunities created by remote auditing, there are also risks associated with auditing suppliers remotely. People worry about auditees hiding hazardous situations or unacceptable environmental conditions such as filth or disrepair. However, unacceptable cleanliness and maintenance practices don’t happen overnight. Therefore, you should expect a clean and well-maintained facility to remain that way. One approach is to alternate between remote and on-site audits to verify the overall condition of a supplier’s facility. Therefore, the risk of auditees hiding objective evidence is more an issue of trust than a highly probable occurrence.

The more probable risks associated with remote auditing are related to the potential lack of availability of records. This is especially important for paper-based quality systems. Most people try to address this risk by scanning paper documents and records, but scanning documents have limited value. Scanning paper documents is more efficiently performed in a large batch by an automated or semi-automated process. Also, auditors and inspectors typically focus on the most recent records, and auditors and inspectors rarely sample 100% of the records. Therefore, the best risk controls include the following:

- Ask a guide to send a digital picture of the record.

- Use a tripod-mounted HD webcam focused on a music stand or similar surface.

- Ask the auditee to read the document while you take notes.

In our experience, you will probably rely on all three risk controls, but it is unlikely to delay the audit. However, in response to the limited physical access to medical device facilities and personnel, certification bodies are sending out questionnaires to assess the risk of being unable to achieve audit objectives or cover the required scope of surveillance and recertification audits. As the audit program manager, you can reduce these risks by working with supply chain managers to develop new supplier questionnaires that specifically ask questions about the capability of supporting audits remotely. In particular, it would be essential to obtain facility maps to identify areas with inadequate cellular coverage and identify records that are only available in hardcopy format.

ISO 19011 – Do you need this quality system auditing standard? Read More »