ISO 10993-1-2018 Biocompatibility – What’s new?

The new 5th edition of the biocompatibility standard, ISO 10993-1-2018, was released in August, and this article explains the changes and potential impact.

ISO 10993-1-2018 is the 5th edition of the biocompatibility standard for the evaluation of medical devices. The new version, released in August, replaces the 2009 version of the standard. I was unable to find a European version of this standard, but you can expect one to be made available very soon–probably before you read this article. If your company is CE Marking devices, once the European standard is released, you will be required to perform a gap analysis against the new standard and assess whether retesting is required for your products to remain compliant with CE Marking requirements.

The FDA has not yet added ISO 10993-1-2018 to the recognized standards database. Still, the FDA guidance on the use of ISO 10993-1, released in February 2016, already addressed most of the changes contained in the new 5th edition.

Overview of Changes in ISO 10993-1-2018

The 5th edition includes a foreword that explains the changes from the 4th edition. The 5th edition replaces the 4th edition (i.e., ISO 10993-1-2009), and it incorporates the correction that was made in 2010. The most significant changes from the previous version are:

- Table A.1 in Annex A, Evaluation Tests for Consideration, was expanded with the addition of six new columns:

- “physical and/or chemical information”

- “material mediated pyrogenicity”

- “chronic toxicity”

- “carcinogenicity”

- “reproductive/developmental toxicity”

- “degradation”

- Instead of tests to be conducted is identified with an “X,” the updated table now identifies endpoints to be considered with “E.” The only column containing an “X” is the column for physical and/or chemical information. This information is identified as a prerequisite for a risk assessment. The new Annex A is now five pages in length.

- The 3-pages that were Annex B, “Guidance on the risk management process,” has been completely replaced with 13-pages from ISO TR 15499-2016, “Guidance on the conduct of biological evaluation within a risk management process.”

- Twenty-one (21) new definitions for terms were added to the 5th edition–including “3.9 geometry device configuration,” “3.15 nanomaterial,” “3.16 non-contacting,” “3.17 physical and chemical information,” “3.25 toxicological threshold” and “3.26 transitory contact.”

- Additional information on the evaluation of non-contacting medical devices and transitory-contacting medical devices was added.

- Expansion of the standard to include evaluation of nanomaterials and absorbable materials. This consists of the addition of section B.4.3.3 in Annex B for guidance on pH and osmolality compensation for absorbable materials.

- An additional reference to ISO 18562-1, -2, -3 and -4, for “Biocompatibility evaluation of breathing gas pathways in healthcare applications,” was added as well. However, the four standards in the ISO 18562 series should be purchased if you are conducting a biocompatibility evaluation for a device of this type (e.g., respiratory gas humidifiers).

There are also many minor changes in the 5th edition, but Annex C is almost identical to the previous version. The only change I noticed was the addition of “Preference may be given to GLP over non-GLP data” to clause C.2.3.

Correspondence with FDA Guidance on Use of ISO 10993-1-2018

Table A.1 in Annex A is quite similar to Table A.1 in the FDA guidance, and 100% of the columns match except the column for “physical and/or chemical information.” Although the FDA guidance does not have a column in the table indicating that physical and chemical characterization is required as a prerequisite for the risk assessment, it is very clear from the language in the guidance that information about the physical and chemical characteristics of the device “should be provided in sufficient detail for FDA to make an independent assessment during our review and arrive at the same conclusion.” FDA guidance also requires information about the surface properties of the finished device. The FDA included a section specific to “Submicron or Nanotechnology Components,” which is consistent with the ISO 10993-1-2018, where there references throughout the standard to ISO/TR 10993-22, guidance on nanomaterials. The FDA guidance does not, however, include guidance on pH and osmolality compensation for absorbable materials. The FDA guidance also does not include a reference to the ISO 18562 series of standards, but the FDA product classification database was updated in June to include a reference to the ISO 18562 series of standards when they were added to the database of recognized standards.

Correspondence with the European Directive and EU MDR

The 4th edition of the EN version has Table ZA.1 explaining the correlation between the standard and the European Directive. Specifically, Clauses 4, 5, 6 and 7 of the European Standard correspond to Annex I, Essential Requirements 7.1, 7.2 and 7.5 in the MDD. In the new Regulation (EU) 2017/745, these clauses correspond with Annex I, Essential Requirements 10.1, 10.2, and 10.4. Therefore, you should expect the European version of ISO 10993-1-2018 to include a table similar to Table ZA.1, but you should also anticipate that your evaluation of biological risks will need to be updated and additional testing may be required in order to remain compliant for any devices that are CE Marked.

Changes to the biological evaluation process in ISO 10993-1-2018

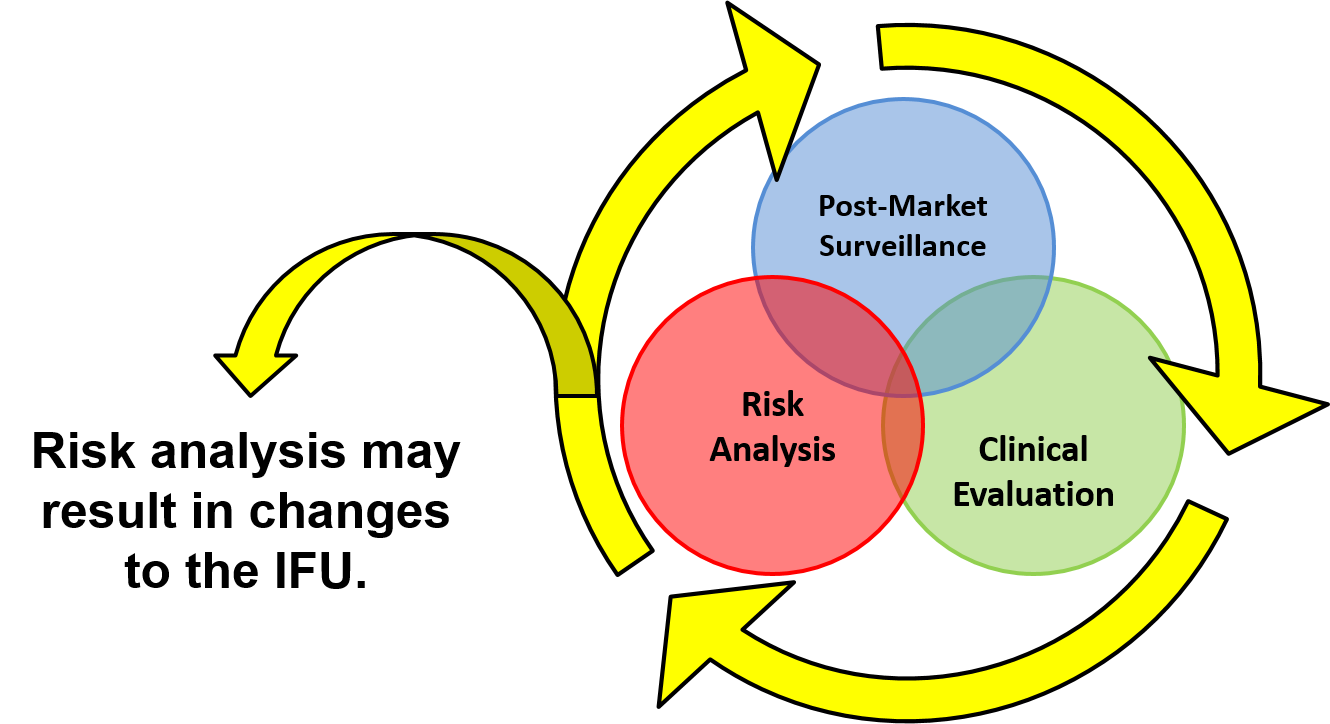

As in the previous version of the biocompatibility standard, Figure 1 is a decision tree that follows the biological evaluation process outlined in the standard. At first glance, the updated Figure 1 appears to be essentially unchanged. However, even though the updated figure has the same shape and the same number of elements, there are subtle changes. For example, the potential effects of geometry are emphasized in the ISO 10993-1-2018. The more significant change in the process is at the end. Where it used to say, “Testing and/or justification for omitting suggested tests,” the updated figure now includes a reference to Annex A under those words. Where it used to say, “Perform Biological Evaluation,” the updated figure now says, “Perform Toxicological Risk Assessment (Annex B).”

Annex B is where the most visible changes are found in the ISO 10993-1-2018. For example, in the previous version of the biocompatibility standard, there was a reference to creating a prospective biological evaluation plan as part of the risk management plan. In the 5th edition, clause B.2.2 outlines the Biological Evaluation Plan–which is sometimes referred to by its acronym of “BEP” by third-party testing labs.

In addition, clause B.4 provides guidance for biological evaluation. This guidance is directly copied from ISO/TR 10993-22, but it answers the frequently asked question of “how do you perform a biological evaluation.” The necessary steps of the biological evaluation, which have not changed, are:

- Material characterization (B.4.1)

- Collection of existing data (B.4.2)

- Device testing considerations (B.4.3)

- Biological safety assessment (B.4.4)

However, the guidance provides details for each step, as well as general guidance on when changes may require a re-evaluation of biological safety, GLPs, and biocompatibility evaluation documentation. In general, the focus of ISO 10993-1-2018 is now on the evaluation of toxicological data in Annex B, rather than passing a few required tests that were previously identified in Table A.1.

Will ISO 10993-1-2018 Require you to Retest for Biocompatibility?

In general, I do not expect that the changes to ISO 10993-1-2018 will require extensive retesting for your company. However, you can expect a significant amount of rewriting of your biological evaluation report to be required. Now you will need to more fully characterize the physical and chemical characteristics of your device, and you will need to provide a more comprehensive biological safety assessment–including an evaluation of toxicological data for each chemical including in the formulation of your device. It’s possible that you may even identify certain chemicals in the material formulation that prevent you from using a material–even though the material may have passed all biocompatibility tests in the past. I will also need to update one of my articles on biocompatibility and a biocompatibility webinar.

ISO 10993-1-2018 Biocompatibility – What’s new? Read More »