The FDA released a new draft 510k predicate selection guidance on September 7, but the draft guidance proposes controversial additions.

On September 7, 2023, a draft predicate selection guidance document was released by the FDA. Normally the release of a new draft of FDA guidance documents is anticipated and there is an obvious need for the draft. This new draft, however, appears to include some controversial additions that I feel should be removed from the guidance. This specific guidance was developed to help submitters use best practices in selecting a predicate. There is some useful advice regarding the need to review the FDA database for evidence of use-related and design-related safety issues associated with a potential predicate that is being considered. Unfortunately, the last section of the guidance suggests some controversial recommendations that I strongly disagree with.

Please submit comments to the FDA regarding this draft guidance

This guidance is a draft. Your comments and feedback to the FDA will have an impact on FDA policy. We are preparing a redlined draft of the guidance with specific comments and recommended changes. We will make the comments and feedback available for download from our website on our predicate selection webinar page. We are also creating a download button for the original draft in Word (.docx) format, and sharing the FDA instructions for how to respond.

Section 1 – Introduction to the guidance

The FDA indicates that this new draft predicate selection guidance document was created to provide recommendations to implement four (4) best practices when selecting a predicate device to support a 510k submission. This first objective is something that our consulting firm recommended in a training webinar. The guidance indicates that the guidance was also created by the FDA in an attempt to improve the predictability, consistency, and transparency of the 510k pre-market review process. This second objective is not accomplished by the draft guidance and needs to be modified before the guidance is released as a final guidance.

Section 2 – Background

This section of the guidance is divided into two parts: A) The 510k Process, and B) 510k Modernization.

A. The 510k Process

The FDA released a Substantial Equivalence guidance document that explains how to demonstrate substantial equivalence. The guidance document includes a new decision tree that summarizes each of the six questions that 510k reviewers are required to answer in the process of evaluating your 510k submission for substantial equivalence. The evidence of substantial equivalence must be summarized in the Predicates and Substantial Equivalence section of the FDA eSTAR template in your 510k submission, and the guidance document reviews the content that should be provided.

Substantial equivalence is evaluated against a predicate device or multiple predicates. To be considered substantially equivalent, the subject device of your 510k submission must have the same intended use AND the same technological characteristics as the predicate device. Therefore, you cannot use two different predicates if one predicate has the same intended use (but different technological characteristics), and the second predicate has the same technological characteristics (but a different intended use). That’s called a “split predicate,” and that term is defined in the guidance This does not prohibit you from using a secondary predicate, but you must meet the requirements of this guidance document to receive 510k clearance. The guidance document reviews five examples of multiple predicates being used correctly to demonstrate substantial equivalence.

B. 510k Modernization

The second part of this section refers to the FDA’s Safety Action Plan issued in April 2018. The announcement of the Safety Action Plan is connected with the FDA’s announcement of actions to modernize the 510k process as well. The goals of the FDA Safety Action Plan consist of:

- Establish a robust medical device patient safety net in the United States

- Explore regulatory options to streamline and modernize timely implementation of postmarket mitigations

- Spur innovation towards safer medical devices

- Advance medical device cybersecurity

- Integrate the Center for Devices and Radiological Health’s (CDRH’s) premarket and postmarket offices and activities to advance the use of a TPLC approach to device safety

Examples of modernization efforts include the following:

- Conversion of the remaining Class 3 devices that were designated for the 510k clearance pathway to the PMA approval process instead

- Use of objective performance standards when bringing new technology to the market

- Use of more modern predicate devices (i.e., < 10 years old)

In this draft predicate selection guidance, the FDA states that feedback submitted to the docket in 2019 has persuaded the FDA to acknowledge that focusing only on modern predicate devices may not result in optimal safety and effectiveness. Therefore, the FDA is now proposing the approach of encouraging best practices in predicate selection. In addition, the draft guidance proposes increased transparency by identifying the characteristics of technological characteristics used to support a 510k submission.

The FDA did not mention an increased emphasis on risk analysis or risk management in the guidance, but the FDA is modernizing the quality system regulations (i.e., 21 CFR 820) to incorporate ISO 13485:2016 by reference. Since ISO 13485:2016 requires the application of a risk-based approach to all processes, the application of a risk-based approach will also impact the 510k process in multiple ways, such as design controls, supplier controls, process validation, post-market surveillance, and corrective actions.

Section 3 – Scope of the predicate selection guidance

The draft predicate selection guidance indicates that the scope of the guidance is to be used in conjunction with the FDA’s 510k program guidance. The scope is also not intended to change to applicable statutory or regulatory standards.

Section 4 – How to use the FDA’s predicate selection guidance

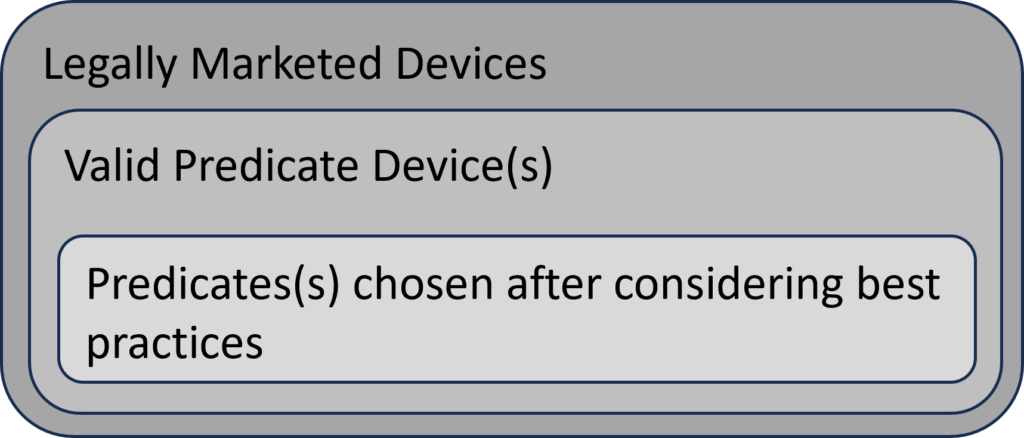

The FDA’s intended use of the predicate selection guidance is to provide submitters with a tool to help them during the predicate selection process. This guidance suggests a specific process for predicate selection. First, the submitter should identify all of the possible legally marketed devices that also have similar indications for use. Second, the submitter should exclude any devices with different technological characteristics if the differences raise new or different issues of risk. The remaining sub-group is referred to in the guidance as “valid predicate device(s).” The third, and final, step of the selection process is to use the four (4) best practices for predicate selection proposed in the guidance. The diagram below provides a visual depiction of the terminology introduced in this guidance.

Section 5 – Best Practices (for predicate selection)

The FDA predicate selection guidance has four (4) best practices recommended for submitters to use when narrowing their list of valid predicate devices to a final potential predicate(s). Prior to using these best practices, you need to create a list of legally marketed devices that could be potential predicates. The following FDA Databases are the most common sources for generating a list of legally marketed devices:

- Registration & Listing Database

- Trade names of similar devices (i.e., proprietary name)

- Manufacturer(s) of similar devices (i.e., owner operator name)

- 510k Database

- 510k number of similar devices

- Applicant Name (i.e., owner operator name) of similar devices

- Device Name (i.e., trade name) of similar device

- Device Classification Database

- Device classification name of similar devices

- Product Code of similar devices

- Regulation Number of similar devices

Our team usually uses the Basil Systems Regulatory Database to perform our searches. Basil Systems uses data downloaded directly from the FDA, but the software gives us four advantages over the FDA public databases:

- The search engine uses a natural-language algorithm rather than a Boolean search.

- The database is much faster than the FDA databases.

- The results include analytics regarding the review timelines and a “predicate tree.”

- Basil Systems also has a post-market surveillance database that includes all of the FDA adverse events and recall data, but it also includes access to data from Health Canada and the Australian TGA.

A. Predicate devices cleared using well-established methods

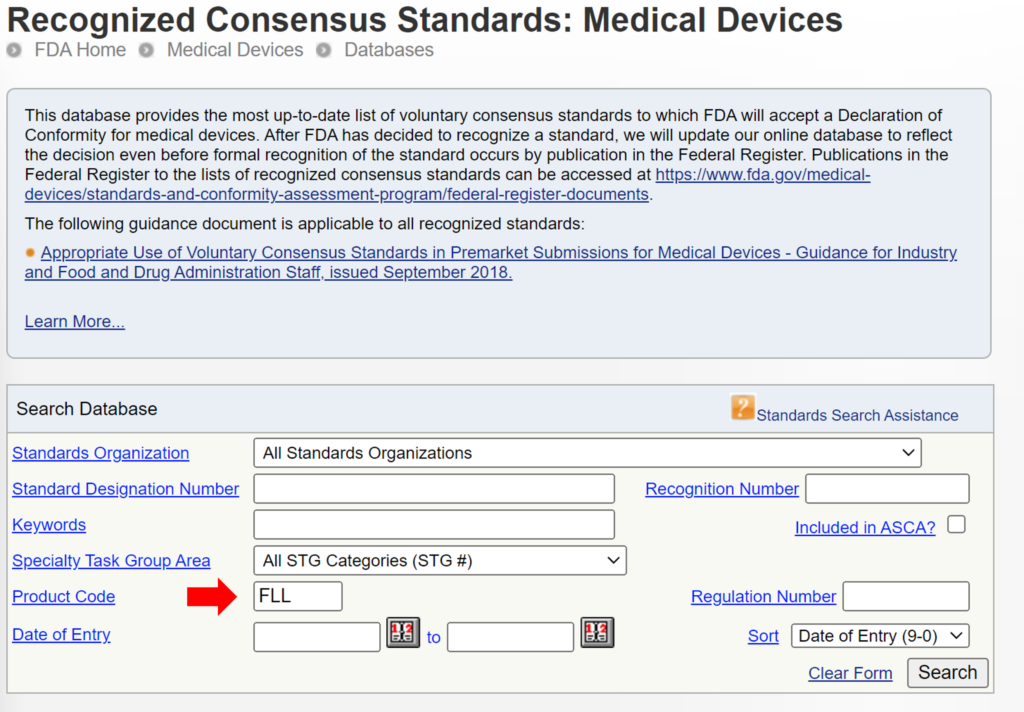

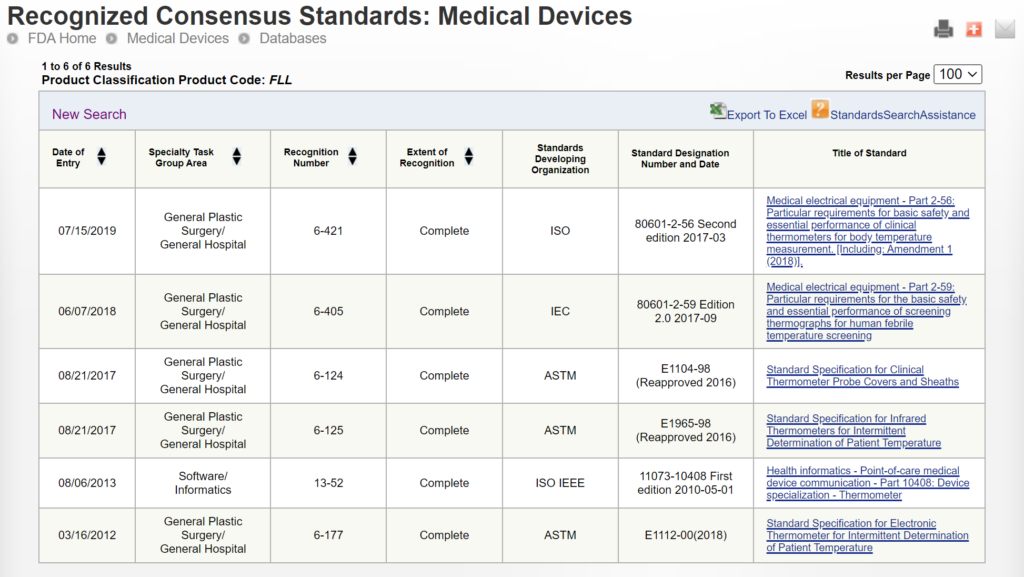

Some 510k submissions use the same methods used by a predicate device that was used for their substantial equivalence comparison, while other devices use well-established methods. The reason for this may have been that the 510k submission preceded the release of an FDA product-specific, special controls guidance document. In other cases, the FDA may not have recognized an international standard for the device classification. You can search for recognized international standards associated with a specific device classification by using the FDA’s recognized consensus standards database. An example is provided below.

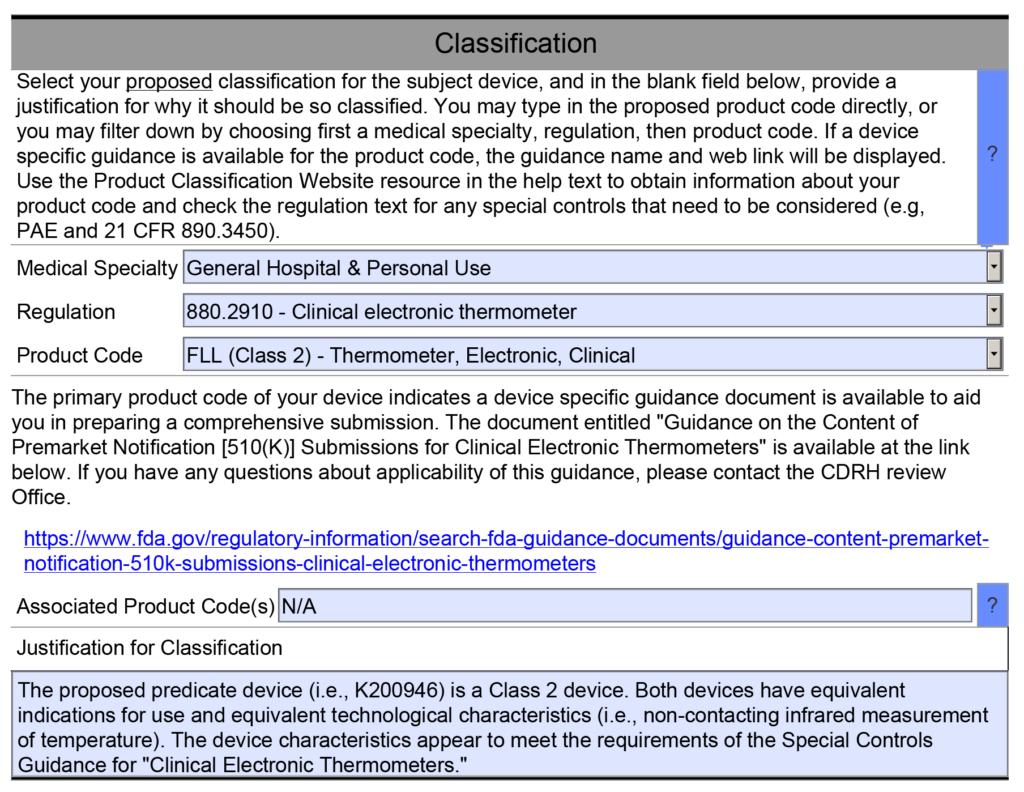

New 510k submissions should always use the methods identified in FDA guidance documents and refer to recognized international standards instead of copying the methods used to support older 510k submissions that predate the current FDA guidance or recognized standards. The problem with the FDA’s proposed approach is that the FDA is implying that a device that was not tested to the current FDA guidance or recognized standards is inherently not as safe or effective as another device that was tested to the current FDA guidance or recognized standards. This inference may not be true. Therefore, even though this may be a consideration, it is not appropriate to require manufacturers to include this as a predicate selection criterion. The FDA is already taking this into account by requiring companies to comply with the current FDA guidance and recognized standards for device description, labeling, non-clinical performance testing, and other performance testing. An example of how the FDA PreSTAR automatically notifies you of the appropriate FDA special controls guidance for a product classification is provided below.

B. Predicate devices meet or exceed expected safety and performance

This best practice identified in the FDA predicate selection guidance recommends that you search through three different FDA databases to identify any reported injury, deaths, or malfunctions of the predicate device. Those three databases are:

All of these databases are helpful, but there are also problems associated with each database. In general, adverse events are underreported, and a more thorough review of post-market surveillance review is needed to accurately assess the safety and performance of any device. The MAUDE data represents reports of adverse events involving medical devices and it is updated weekly. The data consists of all voluntary reports since June 1993, user facility reports since 1991, distributor reports since 1993, and manufacturer reports since August 1996. The MDR Data is no longer updated, but the MDR database allows you to search the CDRH database information on medical devices that may have malfunctioned or caused a death or serious injury during the years 1992 through 1996. Medical Product Safety Network (MedSun) is an adverse event reporting program launched in 2002 by CDRH. The primary goal for MedSun is to work collaboratively with the clinical community to identify, understand, and solve problems with the use of medical devices. The FDA predicate selection guidance, however, does not mention the Total Product Life Cycle (TPLC) database which is a more efficient way to search all of the FDA databases–including the recall database and the 510k database.

The biggest problem with this best practice as a basis for selecting a predicate is that the number of adverse events depends upon the number of devices used each year. For a small manufacturer, the number of adverse events will be very small because there are very few devices in use. For a larger manufacturer, the number of adverse events will be larger–even though it may represent less than 0.1% of sales. Finally, not all companies report adverse events when they are required to, while some companies may over-report adverse events. None of these possibilities is taken into consideration in the FDA’s draft predicate selection guidance.

C. Predicate devices without unmitigated use-related or design-related safety issues

For the third best practice, the FDA predicate selection guidance recommends that submitters search the Medical Device Safety database and CBER Safety & Availability (Biologics) database to identify any “emerging signals” that may indicate a new causal association between a device and an adverse event(s). As with all of the FDA database searches, this information is useful as an input to the design process, because it helps to identify known hazards associated with similar devices. However, a more thorough review of post-market surveillance review is needed to accurately assess the safety and performance of any device–including searching databases from other countries where similar devices are marketed.

D. Predicate devices without an associated design-related recall

For the fourth best practice, the FDA predicate selection guidance recommends that submitters search the FDA recalls database. As stated above, the TPLC database includes this information for each product classification. Of the four best practices recommended by the FDA, any predicate device that was to a design-related recall is unlikely to be accepted by the FDA as a suitable predicate device. Therefore, this search should be conducted during the design planning phase or while design inputs are being identified. If you are unable to identify another predicate device that was not the subject of a design-related recall, then you should request a pre-submission meeting with the FDA and provide a justification for the use of the predicate device that was recalled. Your justification will need to include an explanation of the risk controls that were implemented to prevent a similar malfunction or use error with your device. Often recalls result from quality problems associated with a supplier that did not make a product to specifications or some other non-conformity associated with the assembly, test, packaging, or labeling of a device. None of these problems should automatically exclude the use of a predicate because they are not specific to the design.

Section 6 – Improving Transparency

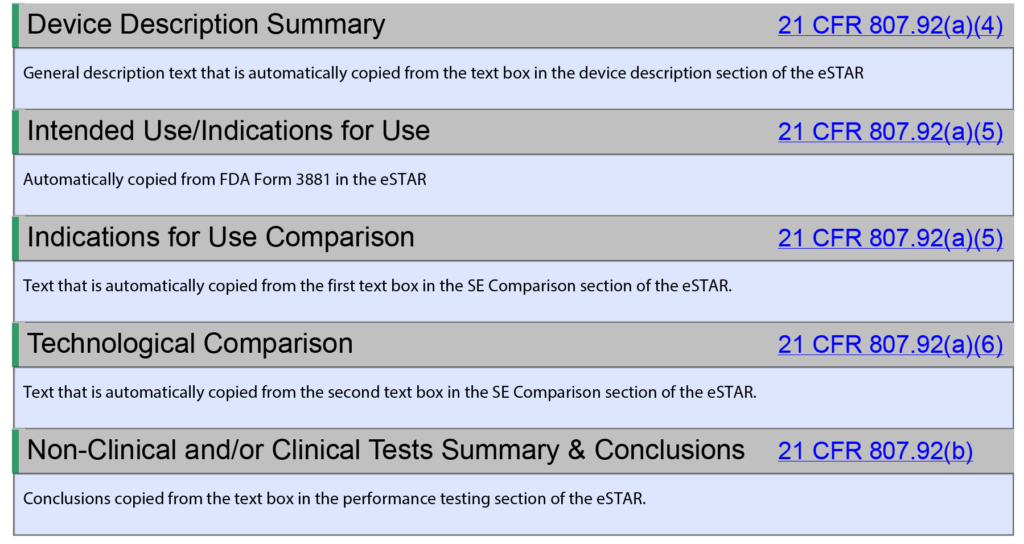

This section of the FDA predicate selection guidance contains the most controversial recommendations. The FDA is proposing that the 510k summary in 510k submissions should include a narrative explaining their selection of the predicate device(s) used to support the 510k clearance. This would be a new requirement for the completion of a 510k summary because that information is not currently included in 510k summaries. The new FDA eSTAR has the ability to automatically generate a 510k summary as part of the submission (see example below), but the 510k summary generated by the eSTAR does not include a section for including a narrative explaining the reasons for predicate selection.

The FDA added this section to the draft guidance with the goals of improving the predictability, consistency, and transparency of the 510k pre-market review process. However, the proposed addition of a narrative explaining the reasons for predicate selection is not the best way to achieve those goals. Transparency is best achieved by eliminating the option of a 510k statement (i.e., 21 CFR 807.93). Currently, the 510k process allows for submitters to provide a 510k statement or a 510k summary. The 510k statement prevents the public from gaining access to any of the information that would be provided in a 510k summary. Therefore, if the narrative explaining the reasons for predicate selection is going to be required in a 510k submission, that new requirement should be added to the substantial equivalence section of the eSTAR instead of only including it in the 510k summary. If the 510k statement is eliminated as an option for submitters, then all submitters will be required to provide a 510k summary and the explanation for the predicate selection can be copied from a text box in the substantial equivalence section.

The FDA eSTAR ensures consistency of the 510k submission contents and format, and tracking of FDA performance has improved the consistency of the FDA 510k review process. Adding an explanation for predicate selection will not impact either of these goals for improving the 510k process. In addition, companies do not select predicates only for the reasons indicated in this FDA predicate selection guidance. One of the most common reasons for selecting a predicate is the cost of purchasing samples of predicate devices for side-by-side performance testing. This only relates to cost, not safety or performance, and forcing companies to purchase more expensive devices for testing would not align with the least burdensome approach. Another flaw in this proposed additional information to be included in the 510k summary is that there is a huge variation in the number of predicates that can be selected for different product classifications. For example, 319 devices were cleared in the past 10 years for the FLL product classification (i.e., clinical electronic thermometer), while 35 devices were cleared in the past 10 years for the LCX product classification (i.e., pregnancy test). Therefore, the approach to selecting a predicate for these two product classifications would be significantly different due to the number of valid predicates to choose from. This makes it very difficult to create a predictable or consistent process for predicate selection across all product classifications. There may also be confidential, strategic reasons for predicate selection that would not be appropriate for a 510k summary.

Section 7 – Examples

The FDA predicate selection guidance provides three examples. In each example, the FDA is suggesting that the submitter should provide a table that lists the valid predicate devices and compare those devices in a table using the four best practices as criteria for the final selection. The FDA is positioning this as providing more transparency to the public, but this information presented in the way the FDA is presenting it would not be useful to the public. This is creating more documentation for companies to submit to the FDA without making devices safer or improving efficacy. This approach would be a change in the required content of a 510k summary and introduce post-market data as criteria for 510k clearance. This is a significant deviation from the current FDA policy.

Example 1 from predicate selection guidance

In this example, the submitter included a table in their 510k submission, along with their rationale for selecting one of the four potential predicates as the predicate device used to support their 510k submission. This example is the most concerning because the summary doesn’t have any details regarding the volume of sales for the potential predicates being evaluated. The number of adverse events and recalls is usually correlated with the volume of sales. The proposed table doesn’t account for this information.

Example 2 from predicate selection guidance

In this example, the submitter was only able to identify one potential, valid predicate device. The submitter provided a table showing that the predicate did not present concerns for three of the four best practices, but the predicate was the subject of a design-related recall. The submitter also explained the measures taken to reduce the risk of those safety concerns in the subject device. As stated above, using the occurrence of a recall as the basis for excluding a predicate is not necessarily appropriate. Most recalls are initiated due to reasons other than the design. Therefore, you need to make sure that the reason for the recall is design-related rather than a quality system compliance issue or a vendor quality issue.

Example 3 from predicate selection guidance

In this example, the submitter identified two potential, valid predicate devices. No safety concerns were identified using any of the four best practices, but the two potential devices have different market histories. One device has 15 years of history, and the second device has three years of history. The submitter chose the device with 15 years of history because the subject device had a longer regulatory history. The problem with this approach is that years since clearance is not an indication of regulatory history. A device can be cleared in 2008, but it might not be launched commercially until several years later. In addition, the number of devices used may be quite small for a small company. In contrast, if the product with three years since the 510k clearance is distributed by a major medical device company, there may be thousands of devices in use every year.

Medical Device Academy’s recommendations for predicate selection

The following information consists of recommendations our consulting firm provides to clients regarding predicate selection.

Try to use only one predicate (i.e., a primary predicate)

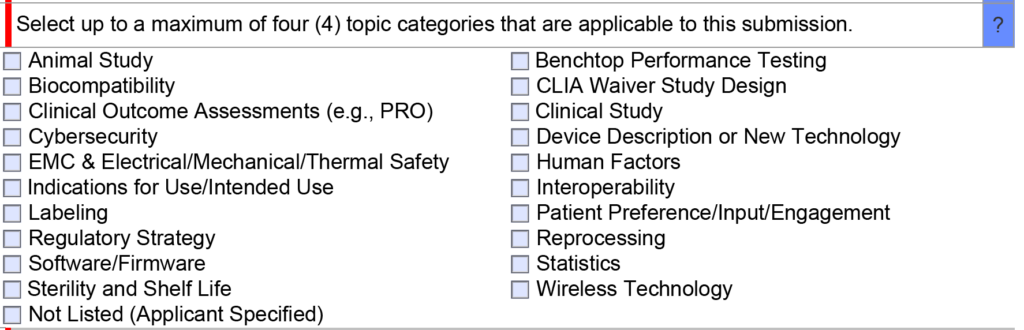

Once you have narrowed down a list of predicates, we generally recommend only using one of the options as a primary predicate and avoiding the use of a second predicate unless absolutely necessary. If you are unsure of whether a second predicate or reference device is needed, this is an excellent question to ask the FDA during a pre-submission teleconference under the topic of “regulatory strategy” (see image below). In your PreSTAR you can ask the following question, “[Your company name] is proposing to use [primary predicate] as a primary predicate. A) Does the FDA have any concerns with the predicate selection? B) Does the FDA feel that a secondary predicate or reference device is needed?”

When and how to use multiple predicates

Recently a client questioned me about the use of a secondary predicate in a 510k submission that I was preparing. They were under the impression that only one predicate was allowed for a 510k submission because the FDA considers the two predicate devices to be a “split predicate.” The video provided above explains the definition of a “split predicate,” and the definition refers to more than the use of two predicates. For many of the 510k submissions, we prepared and obtained clearance for used secondary predicates. An even more common strategy is to use a second device as a reference device. The second device may only have technological characteristics in common with the subject device, but the methods of safety and performance testing used can be adopted as objective performance standards for your 510k submission.

When you are trying to use multiple predicate devices to demonstrate substantial equivalence to your subject device in a 510k submission, you have three options for the correct use of multiple predicate devices:

- Two predicates with different technological characteristics, but the same intended use.

- A device with more than one intended use.

- A device with more than one indication under the same intended use.

If you use “option 1”, then your subject device must have the technological characteristics of both predicate devices. For example, your device has Bluetooth capability, and it uses infrared technology to measure temperature, while one of the two predicates has Bluetooth but uses a thermistor, and the other predicate uses infrared measurement but does not have Bluetooth.

If you use “option 2”, you are combining the features of two different devices into one device. For example, one predicate device is used to measure temperature, and the other predicate device is used to measure blood pressure. Your device, however, can perform both functions. You might have chosen another multi-parameter monitor on the market as your predicate, however, you may not be able to do that if none of the multi-parameter monitors have the same combination of intended uses and technological characteristics. This scenario is quite common when a new technology is introduced for monitoring, and none of the multi-parameter monitors are using the new technology yet.

If you use “option 3”, you need to be careful that the ability of your subject device to be used for a second indication does not compromise the performance of the device for the first indication. For example, bone fixation plates are designed for the fixation of bone fractures. If the first indication is for long bones, and the second indication is for small bones in the wrist, the size and strength of the bone fixation plate may not be adequate for long bones, or the device may be too large for the wrist.

Pingback: 5 Alternatives When You Can’t Find a Predicate Device Medical Device Academy